the tragedy of the 'lady luck'

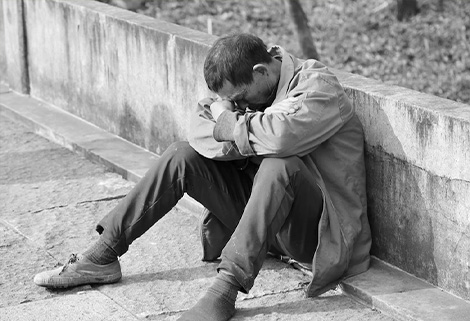

a gruesome tale of murder and suicide on water

Mrs. Morris’ Ordeal

Ernest Spencer owed her £5. For a housewife in Nechells, inner city Birmingham, it was no mean sum; in 1958, £5 was approximately £250 in today’s terms, there was just one catch; she would have to collect it from the narrowboat, ‘Lady Luck’ moored at Tardebigge.

Margaret Ann Morris (51), who lived in Trevor Street, Nechells, had known Ernest Spencer and his wife, Edith, for 32 years. They had been more than friends and neighbours - she and Ernest had lived together for a year; the Spencer’s marriage was far from harmonious. Ernest Spencer, a thick set, squat, heavily built man, had just sold his share of a painting and decorating business to his brother, George, who lived in Saltley, bought an old working boat and, with his wife, Edith, had spent these last ten months converting it into a houseboat.

Nechells in 1958, was a sooty, grimy, unhealthy place. The fiver notwithstanding, Margaret was only too keen for a quick drive into the country, to reclaim her debt and escape the urban squalor for a while. Ernest, after all, was a successful painter and decorator, he must have had some buccaneering flair to him; not many people would choose to renovate and live on an old working boat in 1958, no matter how bad the housing in the blitzed city centre.

Ernest collected her, in his car, from Aston, Church Street, and drove her back to The Lady Luck, moored, with ten other boats, at Tardebigge New Wharf. He was agitated, on edge, not his usual self. At 2:30p.m on Wednesday 29th January 1958, Mrs Morris, stepped aboard the ‘Lady Luck.’ It was deathly quiet but for the puff and grunt of steam engines heaving up the Lickey incline and the hollow shrill of their whistles, echoing around the hills.

The Lady Luck was tidy, everything in order, except forward, in the enclosed well deck, which was ‘stuffed up’ with old coats and a wardrobe shoved carelessly into a corner. Ernest’s eyes were wild, as were his actions, repeatedly he punched himself in the face, babbling; “I’ve done something I’ve meant to do for 32 years,” then he went to the galley, pulled out a kitchen knife from a drawer, and played with it momentarily, before placing it back. “I’ve bought you to the boat,” he explained to Mrs Morris, “...to do you in.”

“Where’s Edith?” Mrs. Morris asked. “At her son’s, in Kingstanding,” was the reply. It was a lie. Behind the wardrobe, beneath a mackintosh and an old brown coat, lay Mrs. Edith Spencer. She’d been dead at least three hours.

Tardebigge, July, 2021

The story of the Lady Luck by came to me by accident. Watching an old Pathé Newsreel, entitled, ‘Is murder increasing?’ there was an eight second segment, with a shot of the new wharf, and, what looked like a sound, comfortable boat of approximately seventy foot. Sixty years on I recognized the place; the serrated rooftops of the boatyard, the Georgian façade of, what was, the Plymouth Arms, while a plummy voice intoned “Quite lately, on a canal houseboat near Redditch, a woman was found killed...”

I’d spent my first winter aboard my own boat in Tardebigge. I’d a nose for local folk-lore and macabre history, yet had never heard about the Lady Luck, why? Surely a swarm of journalists would have made an impression in such a back-water, something to remember, but, whoever I asked, always said they were ‘too young’ or ‘my parents would have remembered but they’re dead,’ no-one could recall the Spencer’s or their narrowboat, Lady Luck.

My first call was to Redditch Library and a trawl through back copies of the Redditch Indicator. There it was, ‘February 1958’ the case of the Lady Luck made front page news. “Man Strangles Wife.” And some of the detail became clear to me. Unfortunately, the paper had been damaged, and the vital details, involving the role of Mrs. Margaret Morris, had been destroyed. So, while moored in Tardebigge, I asked around in Alestones, ‘What d’ y’ know about the Lady Luck?’ Every face was a blank. On Sunday mornings I haunted the churchyard, interrogating parishioners as they left Sunday worship, the nearest I got to any first hand sources was; “I was just a child; I don’t remember.” A wall of silence; Tarbebigge did not want to remember.

Ernest and Edith Spencer

Almost exactly ten years before the Lady Luck another, better known boat, was berthed in exactly the same spot. Tom Rolt and his second wife, Sonia, moored up Cressy and remained there throughout the Second World War. It was there they met Robert Aikman and founded British Waterways. Tom Rolt, as I so often tell anyone who will listen, was the father of all modern liveaboards, and, eleven years later, another boat moored there, an ex-working boat, sides painted black and green, a plywood canopy cast over its hold, which once transported fruits from the orchards of Burcott or fuel from black country, transformed into domesticity, with six windows either side, and two portholes, peering from an enclosed well-deck, like eyes.

Ernest Spencer, born in 1906, must have been a pioneer. He was a painter, decorator, builder, by trade and, after the Second World War, can’t have been in want of work. According to his brother, George Spencer, he sold his share of their joint painting and decorating business and ‘retired’ at the age of 51, and, like many contemporary narrowboaters, must have forsaken finance, for the dream of freedom aboard a boat, after all, 51, was a young age to retire in 1958.

For Edith, however, there is little information. Records show she was born in Yorkshire in 1905 and must have drifted down to Birmingham; she married Ernest Alfred Spencer in the 1920’s. Her life would, most likely, been one of domestic drudgery.

Questioned by the Coroner their son, Edward Albert Spencer, admitted, “There had been troubles.” Saying Ernest had, “left her (Edith) for a time but were back together by September, (1957).” Edward Spencer also testified, “I saw them three weeks ago.” December, 1957, “...they seemed very well.” Tellingly, he added they were “...falsely happy.”

Ernest and Edith, had been aboard the Lady Luck for ten months, they must have moved aboard around about March, 1957, and, if their marriage was in a poor state, with Ernest having once lived in sin with Mrs. Morris, perhaps they thought a joint project, like renovating a narrowboat, would bring them together. Clearly it didn’t.

Murder

Even today Tardebigge is a lonely place to moor. The nearest shop is three miles away and winter there, with long, cold, nights and little distraction is hard enough now, let alone 63 years ago. For Edith, cooped up in a small cabin, further confined by the extremities of winter (metrological reports show 20 days of snow in the Midlands in November alone) with a husband who had recently, and blatantly, been un-faithful to her, was to prove disastrous.

Any couple on a narrowboat will tell you that arguments are not uncommon. A mix of claustrophobia, sharing a small space, inevitably leads to flair ups; in this case it proved tragic. No-one knows exactly what happened when Edith died. Most likely a full blown row erupted between them, careless or hurtful words exchanged. Ernest, in a fury, throttled Edith.

To die by strangulation is a particularly cruel, intimate death. The Pathologist, Professor J.M. Webster found bruising on the left and right neck muscles, her tongue had been forced upwards and there were small haemorrhages in her voice box, temple and eyes, consistent, he testified, to manual strangulation from the front. Ernest would have looked his wife in the eyes as he squeezed the life out of her. It would have taken up to two minutes for life to be extinguished, even under British Law today, such a protracted attack would stand as an act of premeditation. He could have stopped but Ernest saw it through.

With his wife’s body at his feet he then fetched a length of cord and knotted it around the dead woman’s neck, to make certain of her demise, then, hidden her body behind the wardrobe, covered it in old coats then, taking care to lock the boat, climbed into his car and drove to Nechells in search of his erstwhile lover, Mrs. Morris.

Mrs. Morris’ Testimony

District coroner, Mr. B.G.Evers, informed Mrs. Morris, somewhat coyly, that she “need not give evidence that may incriminate her.” She was, after all, a married woman, but she and Spencer had been living together for a year, and implications of sexual assault are chilling.

Mrs. Morris was held, against her will aboard the Lady Luck for about 28 hours, arriving there at 2:30pm, the Wednesday of Edith’s murder. The exchanges with the coroner were reported in full. “Did you stay the night there?” Asked the coroner, “Yes, he made me stay.” “When did you leave the boat?” “About 6:30pm the following day.” “Did he turn you out?” “No. I pleaded with him to let me go.” “Did he threaten to strangle you, or anything of that sort?” “Yes.” “Did he attempt it?” “No.” “Did he say anything about his wife then?” “Well, he said ‘I have done something I have been waiting to do for 32 years.’” “Did he indicate what that was?” “He put up his hands and said ‘with these.’” “When you say he was ‘different’ can you give any indication as to his state of mind?” “Well, his eyes looked wild and he was walking up and down and knocking his head with his hands.” “What did he tell you to do when people were walking along the towpath?” “Hide.” “And in order to get away from him...did you, in fact, have to promise you would return next day?” “Yes.” “That was in fact, a trick?” “Yes.” “You had no intention of returning the next day?” “No.”

Placated by this promise, Spencer drove Mrs. Morris back to Trevor Street, Nechells, she added further disturbing details. “He (Spencer) had always said he would do harm to his wife. He had threatened to do so on previous occasions and I did not think this was more serious than the others.” “After you left him in August you did not return to him?” “No.”

“You returned to your husband to whom you told the whole story?” “That is right.”

End Game

On Thursday, 30th of January, Ernest spent a long night, alone, aboard the ‘Lady Luck,’ the enormity of his actions sinking in. The homicide act, which limited the number of capital crimes, had been passed one year previously, and, while uxoricide no longer carried a statutory death sentence the prospect of an ignominious end on the gallows at Winson Green must have been on his mind along with the dawning realization that his lover, Mrs. Morris, reconciled with her husband, would not return to him.

Un-able to sleep he instead began writing a series of notes, the longest of which ran to several pages and was addressed to his Brother, George Spencer of Chartist Road, Saltley. On Friday he went straight to the nearest post office, located in Aston Fields, three miles away. There, he registered his letter and sent a telegram to his son, Edward, telling him to go immediately to his Uncle’s house. George’s boat, a small, cruiser type, painted red and white was moored just in front of the Lady Luck, George would know where to find him; to make sure, he used the telephone in canal inspector’s office to call his Brother that Friday evening.

To those who saw him that day, they claimed he “appeared quite normal.” His communique’s sent, he returned to the boat, unable to spend one more night there, alone with his thoughts and the corpse of the woman he’d throttled, still hidden beneath old coats behind the wardrobe. He locked the door from the inside, took a spoon, a glass of water, then a box of aspirins, poured the pills on to a sideboard and proceeded to crush them into a fine white powder. He then spooned it into the glass and drank it down. His final sensations would have been dizziness, shortness of breath, palpitations, maybe even hallucinations before, finally, suffering chest pains as he struggled to breathe. Collapsing forward, he struck his nose on the sideboard, causing a small abrasion. Ernest Spencer, like his victim hidden behind the wardrobe, died of asphyxiation.

Discovery

At 1:45p.m, Saturday, four police officers, led by Det. Inspector G.J. Davies of Bromsgrove and G.V Sedgwick of Redditch arrived at Tardebigge New Wharf by car, having been alerted by George Spencer. Police Constable Smith of Aston Fields described how they found the key to the boat, under a stone, near the stern entrance, and then forced the latch by reaching through the Kitchen window. On entering they were assailed by what was described as a guard dog, which had to be driven into another part of the boat. The door to the front compartment had been jammed shut, but, with some effort they heaved it open to discover Ernest, fully clothed, lying face down, and dead on the floor, followed by Edith behind the wardrobe. Ernest Spencer had cheated justice.

The bodies were removed to Bromsgrove mortuary where Professor Webster carried out an autopsy. On Sunday, relatives from Saltley, probably the brother, George, formally identified the bodies as that of Ernest and Edith Spencer. Next Wednesday, a week after Edith’s murder, a ninety minute inquest was held at Bromsgrove magistrate’s court.

The Final Insult

At the inquest the Coroner advised the jury that there were three possibilities: That Mrs Spencer had died accidently as the result of ‘rough and tumble.’ That Mrs. Spencer had provoked her husband, verbal provocation would have been enough, hence a verdict of

manslaughter or that she had been wilfully murdered.

Although the details of the notes left by Spencer and the letter sent to his brother were not made available to the press, one, particularly nasty detail, in what today’s parlance would be called ‘victim blaming,’ came out. In one of the notes Spencer claimed his wife came at him threatening to ‘scratch his eyes out.’ However, he was a powerfully built man - physically Edith would have been no match for him, borne out the Pathologists evidence. “Were there any marks on him that may have been caused by scratching?” “I could not see any which may have been caused by another party. There was a tiny abrasion on the second right knuckle but it did not seem to be anything that had been scratched out of him at all.”

Happily, the jury returned a verdict of wilful murder, despite Mrs. Morris’ testimony that he ‘was not in his right mind,’ his actions, writing to his Son and Brother, coolly using the canal inspectors telephone, securing the boat, all pointed to him being responsible for his actions.

On Friday, 7th February, exactly a week after his suicide, the bodies of Ernest and Edith Spencer were buried in an unmarked grave in St. Bartholomew’s, Tardebigge a graveside service conducted by the Rev. R.W. Underhill.

Remember Edith

On a drizzling day in February, almost 64 years to the day of their funeral, I found myself picking my way through the long grasses, the weathered and dilapidated tombstones and monuments in Tardebigge churchyard. Wiping the droplets from my phone, I read and re-read the e-mail that Jane Hall, the churchwarden had sent me. “The graveyard at Tardebigge is a bit higgledy-piggledy but we have the plot noted as row 14, plot 31...

interestingly Alfred is the only Christian name in the register but I checked the names against

the genes reunited website and couldn’t find Alfred Spencer but found; Ernest A Spencer who died in Bromsgrove district, 1958 aged 51.”

I’d become a little embarrassed asking ‘round Tardebigge about this case but Jane could not have been more obliging. Tantalizingly, she told me that the Rev. Underhill’s widow, still lived in Tardebigge and, although she was a centenarian, was still mentally sharp. She contacted Mrs. Underhill’s son, on my behalf, but I heard nothing back. All these years later, still no-one wanted to talk about the tragedy that unfolded on the Lady Luck, all those years ago.

I found the grave, un-marked, but for the mound of sandy soil, on the extremities of the churchyard, strewn with brambles and pitted with rabbit warrens it was almost impossible to tell there was a grave there at all, but the records bore it out. The last resting place of the Spencer’s, ironically, over-looking the place where the Lady Luck had been moored.

It was fitting that I, another liveaboard boater, albeit from another age, should track them down; the Spencer’s were strangers to Tardebigge, outsiders like myself, buried quickly and forgotten quicker. Yet it pained me to think that Edith shared her grave with her killer and shared his ignominy. The case of the Lady Luck was, like any other squalid, domestic murder, of a kind repeated over and over again, year after year; a husband, murdering some-one whom he once purported to love. Perhaps it was the novelty of it occurring on a houseboat which bought the Pathé Newsreels here, and bought me here too, over half a century later?

It is a tale like so many others; a volatile, unfaithful husband who repeatedly threatened to murder his wife, warnings which went ignored until too late. A woman, robbed of a happy retirement, robbed of seeing children and grand-children, robbed of a decent grave and a decent memorial, locked in eternal bondage in the sandy soil with her killer.

It is a sad end to this sorry story but it is a story we must never forget. Remember Edith. Remember her.

If you are fitting out a new canal boat or maintaining an existing narrowboat you need to be able to find suppliers who specialise in narrowboat furniture.

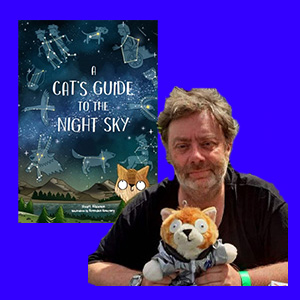

If you are fitting out a new canal boat or maintaining an existing narrowboat you need to be able to find suppliers who specialise in narrowboat furniture. Stuart Atkinson is an amateur astronomer who lives in Kendal. He has written many books for children, both fact and fiction, and is passionate about sharing his love and knowledge of stars and the universe with campers, caravanners and boaters - with anyone who ever has the opportunity to look out on the sky at night.

Stuart Atkinson is an amateur astronomer who lives in Kendal. He has written many books for children, both fact and fiction, and is passionate about sharing his love and knowledge of stars and the universe with campers, caravanners and boaters - with anyone who ever has the opportunity to look out on the sky at night.