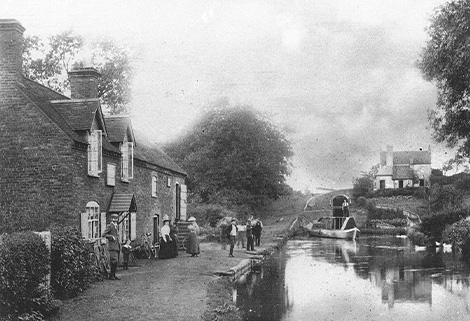

I have just had a very enjoyable little jaunt down to Gloucester and back collecting a dear little boat named Spindrift for Heatherfield Heritage. The journey sent me travelling down my favourite canal, the Staffs and Worcester, and I thought for this piece I would take you on a little tour of the cut.

This canal is old. Despite being started slightly after its sister, the Trent and Mersey, it was actually completed first and was open through its length in 1772.

At one end Stourport hunkers down like a grumpy toad. The town basically owes its existence to the canal and was described in glowing terms by Nash in the 18th century "...stood a little alehouse called Stourmouth. Near this Brindley has caused a town to be erected, made a port and dockyards, built a new and elegant bridge, established markets and made it a wonder not only of this county but of the nation at large.." but truthfully it was much like any other town with fighting, drinking and ladies of negotiable affection.

A case in 1832 gives us a little from each category. Charles Hodgkiss, a man of 44 described as “a tall stout built man, of a altogether most repulsive aspect, and having a broken nose” fell out of the pub and started bellowing for “the best man on the severn'' to come and fight him. What transpired after that is open to conjecture, but he found himself on trial for the murder of another boatman, Francis ‘Old Frank’ Wassall. He was accused along with 19 year old William Cooke, who tried to turn King's Evidence and put all the blame on him, but luckily for Hodgkiss, Cooke was useless; at the initial inquest he claimed to be in the arms of one “Mrs Green, who is known as 'the thick legged one'", and then at the trial changed his mind and said he’d seen Hodgkiss beat Wassall and then push him into the water. The judge, quite rightly, dismissed his evidence.

Leaving the basins of Stourport, the canal winds around Mitton under the curious little bridge that gives access to the remains of Mitton chapel and the sprawling cemetery. The site is on its 4th church in the 800 or so years, with the construction of the canal being no small part responsible for the turnover.

You pass next the mighty walls of the railway and the remains of the canal basin that served it. Somewhat innocuously stuffed onto a modern wooden post is a small iron roller, apparently original to the site and used to assist in getting boats out of the basin.

The canal stays within sight of the Stour as it progresses, and in the quiet green surrounds the towpath suddenly rises up on a bridge over a small gap. This is the remains of the somewhat unfortunately named “Pratts Wharf '' and the lock that dropped boats onto the river so they could scoot a mile or so along to Wilden. Wilden had an ironworks from about 1670 and had relied almost solely on the river until the advent of the canals. There was a wharf there almost as soon as the navvies had packed up their bags but the site faded into obscurity until the canal link was built in 1835. Once it was a hive of activity with a lock keeper's house, workshops, and even a boat dock.

We now reach Falling Sands lock. Much like Pratts Wharf, this location too is a quiet shadow of its former self. Up until the 60s, when it was finally knocked down, a 3 bedroomed cottage and appropriate outbuildings stood over the weir (including the lavatory. I trust the reader can work that innovation out without illustrations!), and knowing there is now a building missing makes it far easier to understand how one Charles Wyer made the mistake of getting caught leaving a paddle up in 1869, meaning the water "ran unchecked for 8 minutes." It was the second time he'd done it and he found himself spending fortnight in jail with hard labour. The Staffs and Worcester company were very very keen when it came to taking boatmen to court for wasting water or damaging locks, and lock keepers were their eyes and ears when looking for miscreants. For example, further up the line at Whittington, 2 young men turned a lock despite the keeper telling them they needed to wait until another boat came the other way and were fined 2 shillings, while another man who turned Hyde lock "for spite" was fined 5. You can feel the frustration of the boatmen, who were losing precious time, and the despair of the company, who were fighting a losing battle trying to ignore the railways. (The Staffs and Worcester company were infamous in their abject refusal to deal with railways, even at the cost of profit to their shareholders. They were still trying to pretend railways didn’t exist when they were finally nationalised in 1947)

We now reach Kidderminster, a town of course much famous for its carpets. Today, the canal passes by long bricked-up arms that hint at bustle the waterways of Kidderminster once saw, but really it’s quite difficult to see the past here. Kidderminster was close enough to Birmingham that it dealt with a high proportion of day boats trundling back and forth. Although they’re often dismissed today in favour of the more ‘romantic’ long-distance boat, day boats could earn a lot of money. In 1861 one boat was hired by the New British Iron Company to move timber from Kidderminster to Corngrave, a day's journey of about 20 miles and 30 odd locks, at the agreed price of 7s per tonne, roughly £40 in today's money. She was gauged at Kidderminster as carrying 20 tonnes, but then gauged at the BCN as carrying 13. The boatman wanted 20 tonnes worth of payment, (£7 old money), but the company would only pay for 13 (£4 10s). The boatman took the company to court for the difference, and the poor judge had to sit through a variety of witnesses from each side until eventually someone had the bright idea of actually calculating the weight and realised the boat must have been carrying 14 &½ tonnes. He ordered the company pay the appropriate money to the boatman and suggested the company “do their own mathematics in future.” In today's money, that's about £580 for a long day's work. Obviously there were overheads (tolls, horse care, boat maintenance) but that’s a healthy wage.

Most of the day boats were worked by grown men but occasionally children would be put at the tiller. At the next lock of our trip, Wolverley Court, a dreadful example of this was enacted in 1869 when 11 year old Frederick Millington and his 13 year old brother William brought an empty boat from Stourport on the instruction of their father. Frederick slipped at the head of the lock, was sucked into the paddle-hole he had just opened and killed.

Their father was berated by a disgusted coroner who couldn’t understand why 2 children were sent out with a boat, but a look at the records show that their father, another Frederick, was a boater-cum-coal-merchant with a growing family to support; he needed the help of his two sons to keep food on the table.

Next on the line is Wolverley Lock. Supposedly, the ghost of a man has been seen by the canal bridge, which could perhaps be attributed to when an 83 year old man named Henry Gillet had sat on the bridge and for whatever reason fell backwards, rolled down the bank and straight into the water. On being rescued he allegedly said “I thank you all. The Lord have mercy on my soul and my poor cat.” He was taken home and put to bed, where he drifted into unconsciousness after saying “It is all a dream, but it has come for my end” and never woke up.

Like most canal locks, Wolverley has seen its share of accidents, but one in particular was “noteworthy”. In 1856, a boy sent ahead to get the lock ready and slipped with predictable results. What made it juicy for the newspapers was that, having drained the lock and got the appropriate ropes and ladders (for this is long before the advent of sturdy metal ladders bolted securely into the brickwork), no one would go down to try and find the boy despite there being “several strong men on the the spot.” At length, one Mrs Hancock was passing in her carriage, stopped on the bridge to find out what the commotion was and commanded her butler into the lock to retrieve the corpse.

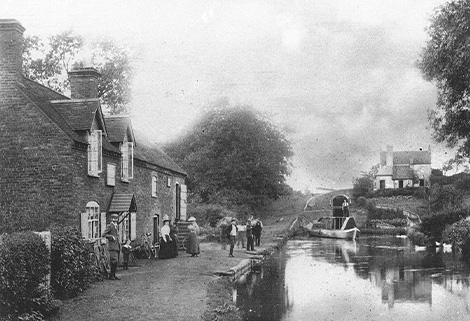

The lock is kept company by the imaginatively named “Lock inn”, which actually predates the canal by a considerable age, originally being a selection of cottages. Like most canal side pubs, the landlords weren’t averse to trading beer for cargo and so there are numerous stories of boats coming away lighter than they ought and their crews drunker than they should.

Boaters were often quite free with the cargos they were carrying; in 1848 at this lock, a young man recorded only as Boden heaved 1 &½ hundredweight (75kg) of coal off the boat and brazenly asked the lock keeper if he had a wheelbarrow he could borrow. When he and his young companion were arrested, their defence was that there was extra coal on board for their use and it was their right to take it away. The company employing them denied it strenuously and both boatmen were put in jail for a week.

Leaving Wolverley the canal starts to take on a craggy, rocky aspect. At Debdale lock, cut deep into the rock beside it, is a strange little doorway into a hill. Entering it does not take you into Narnia, but into a single room with what appear to be benches cut into the stone on one side and what could be taken as a bed hole the other. Bizarrely, and despite the obvious flaws with the theory, it has gained the legend that it was used as a canal stable. My research, and practical experience, can find no evidence to support the idea of it being used as a stable. I have found evidence of it being used as a shop though, and a brief mention of it being used as accommodation for a lock keeper before the actual lock keepers’ house was complete.

You next pass the former entrance to the Cookley Ironworks. Today the site makes steel wheels, and the story goes that one in eight wheels used in WW2 war effort were made there.

Just 100 yards from the old arm you enter into the tiny tunnel. It’s a grand total of 65 yards long and has its own towpath, which the local boys would dare each to stay on when the boat horses would pass through. This challenge was made all the more risky by the very real possibility of an angry boatman leaping out of the darkness and giving the boys a tanning.

You come back into the sunshine and into leafy spaces as the canal comes through to Whittington. Boatmen were not above a spot of poaching to supplement their diets, and had you stood on Whittington Horse Bridge in 1851, you’d have witnessed what was a surprisingly common accident. 22 year old Isaac Starling was at the tiller of his boat when he spotted a suitably juicy looking morsel, reached down into the cabin, grabbed the barrel of the gun propped up against the side bed and whipped it up, catching the trigger in his haste and, basically, blowing half his face off. At the inquest, his companion and another boatman who appears to have been travelling butty with them, resolutely stuck to the story that Isaac was shooting at rooks and the coroner accepted it, despite knowing what was really going on. There was, after all, no benefit to bringing up poaching when only a boatman was dead instead of a pheasant.

The river Stour winds peacefully beside the canal as we arrive at Kinver, once powering mills for cloth and metal working. The canal's arrival gave Kinver the trade routes to prosper into the charming village it is today, with an excellent chippy that is as good a reason to stop as any. There are also the infamous rock houses, now cared for by the national trust.

The canal here has been stocked for fishing for many years, and suffered quite badly with people poaching Lord Stamford’s fish whenever they could get away with it. In 1904 the Staffs and Worcester company took a number of men to court for having actively drained the canal down to a foot depth so they could spear fish for eels.

Appropriately for our purpose in collecting Spindrift, a former steam launch, in 1913 the lock witnessed “ A Kinver Recontre. We do not know if the following incident has any connection with the desire on the Part of certain authorities to make more use of the canals and waterscape of England, but on Tuesday the somewhat unusual sight of a fairly large but shallow draught steam launch passing through the Kinver lock was seen. The launch was the "Dora," of Liverpool, and in the course of an interview her engineer said that the boat had started from Liverpool some five weeks ago, and had proceeded across England by canal and river..”

Leaving Kinver we come up to Hyde, once the site of a fat works. In the 1860s fat was quite a valuable commodity, which is why James Dobbin finally snapped and stole a sack with some 23kg of fat in it and sold it on. His customer, a rag and bone man named Thomas Ogan, bartered a lift from a boat passing through Hyde Lock (who wants to walk carrying a sack of fat after all.) Unfortunately for both men, the company quickly noticed the fat was gone and they were arrested and sentenced to jail.

Next up we come to Dunsley Tunnel. It is perhaps a misnomer to call it a tunnel as it’s only 25 yards long, but it has still managed to attract a ghostly reputation of a shadowy woman who vanishes if you get too close. Perhaps she is something to do with 18 year old Ellen Waldron who allegedly went mad and jumped in the canal. She was a “rather stout” young woman standing at a miniscule 4’2", with dark hair and grey eyes. She was described as having “weak intellect” and being “a simple body” and for some reason the newspaper seemed really quite taken with the fact she wore rubber galoshes.

Stewponey is our next stop. A name that has never been satisfactorily explained, although it was drily noted in a diary as being appropriate following an animal cruelty case in 1873 concerning a boathorse that ultimately had to be put down. The wharf here was a busy little transhipment point, and in 1871 you would have seen 18 year old Charles Moss and his little brother Francis, aged only 9, regularly bringing their mother's boat here with day cargo, such as the intriguingly described “artificial manure”.

Stourton junction tempts you to turn right but our journey sent us straight on and to the sharp

left hand bend that puts you onto Devil’s Den.

The Stour runs under a small aqueduct, and just beyond the aqueduct is a tantalising door into the rockface. Apparently behind that door, erected supposedly to ‘protect the bats’, is a small boathouse that was the bargaining chip the Foley family demanded in return for allowing the canal over their land. With a name like Devils Den, you won't be surprised to read that there are a variety of legends surrounding that woodland, all roughly of the same theme.

The Stour runs under a small aqueduct, and just beyond the aqueduct is a tantalising door into the rockface. Apparently behind that door, erected supposedly to ‘protect the bats’, is a small boathouse that was the bargaining chip the Foley family demanded in return for allowing the canal over their land. With a name like Devils Den, you won't be surprised to read that there are a variety of legends surrounding that woodland, all roughly of the same theme.

Gothersley lock is next. It is pretty enough today, though it too has lost its cottage. It is a sad lock though, where in 1915 Thomas Humfries was clearing ice from the lock with a pole when he slipped and fell in. His wife managed to grab his hand but he slipped from her grasp and drowned. Equally sad, in 1856 the lock keeper's daughter was returning home from an errand when a labourer named James Cox brutally assaulted her. She was just 16 years old.

Next along is Rocky lock. This one comes with a spooky reputation, where people have reported being pushed and shoved, along with a general feeling of being watched. As locks on the Staffs and Worcester go it’s a fairly shallow one, and that fact makes the following story all the more curious.

In 1836, William Corker, his wife Ann and her two children, Martha and Elizabeth, were bringing a boat from “Etruria to Bilston” when they got to Rocky Lock. William was driving the horse and Ann was at the tiller, and once the boat was in the lock Ann stepped off to work the lock with her husband.

What happened next is something of a puzzle, for a boat going to Bilston would be going downhill, yet the newspapers report that “..the stern of the boat caught in the lower gates and prevented it from rising and the boat was filling with water. At this moment, the husband who was at the top of the lock called out to his wife to pull up the bottom paddles, whilst he let down the paddles at the upper end to prevent any more water from entering the lock. Instead of attending to his instructions she… jumped into the cabin and the boat instantly sunk. Although assistance was promptly obtained.. It was a full 20 minutes before the bodies could be got out of the water..”

Now, it’s plausible that the reports have simply mixed up the locations; a boat going from Biltson to Etruria would be going uphill and it would also tie in with why the inquest, and burial of the woman and children, took place in Penkridge. But there are question marks in the tale that suggest that maybe, just maybe, something more sinister than an accident took place nearly 200 years ago.

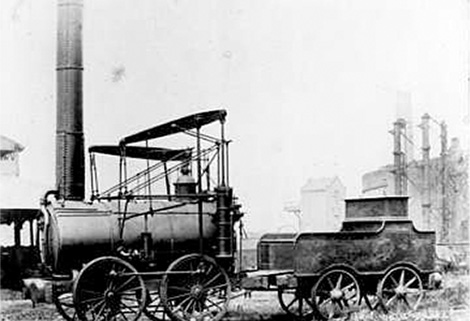

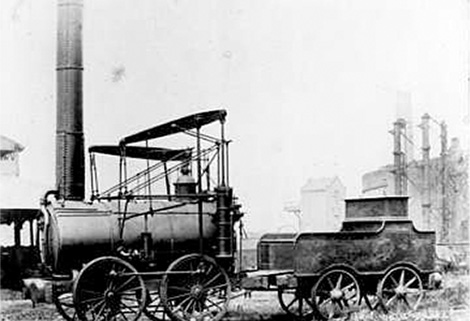

Leaving behind the eerie lock you come past Ashwood basin, a place that could be arguably described as one of the first intermodal freight terminals. Here, the locomotive ‘Agenoria’ held court from 1829 until 1864, when she was basically dismantled and stuffed in a shed. She was rediscovered in 1884 and eventually given to the Science museum. She now lives in York in the National Railway Museum.

Greensforge is our next stop. In 1905, on April Fools day, the canal breached above the lock in a blowout some 30 feet wide and 15 feet deep. A boatman coming down sent his son to set the lock and initially dismissed the boy’s excited report; “Get away wi’ yer. D’ye think I don’t know what day it is?” but found him to be correct. In a feat that I doubt would be matched today despite the technological advances, the Canal Company engineers descended on site and had it open to traffic in a week. Of course there was a small hoard of tetchy boaters either side of the worksite, which may have spurred the work on.

Proportionately speaking, Greensforge Lock it seems to have been one of the most dangerous locks on the canals, with such a cheerful variety of drownings, maimings and general accidents that even the canal company itself was getting puzzled. Some more recent accidents are of course due to active human stupidity; for example in 1970 when a 16 year old boy said to his friends “I bet I can jump the lock” and had to be fished out when he discovered he could not in fact make the distance.

Moving on, the canal takes you up to the little village of Hinksford. There was quite a fuss in 1884 here when a boatman bashed a hare with a cabin shaft and refused to give it to the Earl of Dudley’s gamekeeper, who had witnessed the whole thing. There was apparently a “tussle” over the hare, and presumably the boatman was the winner for he found himself being fined 20 shillings for killing game without a licence.

Hinksford and its neighbour Swindon appear repeatedly in the archives with young women having “criminal conversation” with men they were not married to and perhaps this is something to do with the ‘The Boat Inn’ just along the line below Botterham Staircase. Legend says that the building was originally constructed as a sort of hostel while the canal was being built, and that it quickly became little more than a brothel. When the canal was completed, they extended the building out to add a 12 horse stable and it was turned into a boaters' pub. How long it kept up its sideline, if the story is even true, is unknown, but one man noted in 1876 that you could get “a good dollying” at the Boat. I wouldn’t like to say whether he was referring to laundry or ladies.

The canal now edges back into urban sprawl with Wombourne and winds along under Giggetty and Houndel before depositing you at Bumblehole Lock. This is not THE bumblehole that everyone thinks of when they’re talking about the Black Country; it appears that this Bumblehole is merely an abbreviation of Bumble Hole Meadows.

A few hundred yards down the canal you now reach the bottom of Bratch Locks. (Incidentally, if you are like me and you enjoy taking childish photos with funny street signs, get on the road at Bratch Bridge, turn right and walk down about half a mile. You’ll find the delightful named Billy Bunns Lanes)

The Bratch is a very pretty location but also something of a mystery. It now has 3 locks with a pound about 6ft long between them, and side ponds. It was not originally like this; Brindley set them out as a 3-lock staircase (it has been claimed it was originally a 2-lock) which was open around 1770. Shortly afterwards, perhaps around 1800 when the tollhouse was built, the locks were stripped back and rebuilt into their present form. Allegedly, this involved leaving the top lock alone and moving the middle and bottom locks back about 20ft to allow for the fitting of gates. This theory works quite well when you also look at Bratch lane at the bottom; it has a kink in it that would match the idea of the locks being brought backwards. The remains of the original cills are visible when the ‘new’ locks are drained and as a bonus wave from the past, if you look at the little bridge crossing the stream by the road bridge, you’ll see rope marks - the stone has been reused from copings.

Leaving Bratch you come back into the countryside for a few miles before you reach the urban creep of Wightwick (pronounced Wittick.) Wightwick is home to Wightwick Manor, and if you have any interest in art or gardens, it’s well worth a visit.

Now we arrive at Compton Lock, the first one Brindley built on this canal. It too has lost its keepers’ cottage, from where Mrs Filkin came rushing out in 1865 to yell at Henry Hodson and ended up in what appears to be a slanging match. Hodson, his boat heading downhill, pushed his horse on and forced the gates open when there was apparently nearly 2 feet of water still to go, damaging the gates and quite probably his horse.

To your right you will soon see the junction to the Birmingham Main Line at Aldersley, but we carry on Autherley and the Shropshire Union Canal.

Of all the tales I’ve found around Autherley, my favourite is from 1862 when a boatman named John Vickerstoff was arrested for stealing 5 bushels (somewhere in the region of 135kg) of potatoes from a nearby field. The evidence was imprints of someone kneeling in the soil wearing a pair of corduroy trousers and that the boatman was wearing corduroy trousers, and boot prints that were heading in the direction of the junction. A witness was found who said he’d seen Vickerstoff at the junction and said hello to him, and that he had no potatoes with him. The policeman was absolutely certain that Vickerstoff was guilty but the magistrate was having none of it: “no potatoes, no prosecution.”

We moved onto our first narrowboat in June 2009 after 2 years living on wild & wonderful Anglesey. Initially, we both took a year out in order to fully embrace our plan to cruise here, there and everywhere, but by the end of that year, we had both fallen completely in love with the cut, the people on the cut and boat life, so I took on various freelance drama coaching jobs and Pete became a boat husband!

We moved onto our first narrowboat in June 2009 after 2 years living on wild & wonderful Anglesey. Initially, we both took a year out in order to fully embrace our plan to cruise here, there and everywhere, but by the end of that year, we had both fallen completely in love with the cut, the people on the cut and boat life, so I took on various freelance drama coaching jobs and Pete became a boat husband!

Please visit our

Please visit our

The Stour runs under a small aqueduct, and just beyond the aqueduct is a tantalising door into the rockface. Apparently behind that door, erected supposedly to ‘protect the bats’, is a small boathouse that was the bargaining chip the Foley family demanded in return for allowing the canal over their land. With a name like Devils Den, you won't be surprised to read that there are a variety of legends surrounding that woodland, all roughly of the same theme.

The Stour runs under a small aqueduct, and just beyond the aqueduct is a tantalising door into the rockface. Apparently behind that door, erected supposedly to ‘protect the bats’, is a small boathouse that was the bargaining chip the Foley family demanded in return for allowing the canal over their land. With a name like Devils Den, you won't be surprised to read that there are a variety of legends surrounding that woodland, all roughly of the same theme.

I was 30 years old when I first set eyes on a proper canal and now over 40 years on I’m still a devoted ditch crawler. I bought my first narrowboat from Stoke on Trent in 1986. Then in 1998 I got the chance to buy a fine replica Dutch Barge, Saul Trader, and begin to plan a series of voyages from Gloucester, across the English Channel to France, Holland and Belgium. My books are the stories behind our voyages, and whether you’re an established enthusiast, a boater or an armchair follower I hope you will find some pleasure and enjoyment from my ramblings.

I was 30 years old when I first set eyes on a proper canal and now over 40 years on I’m still a devoted ditch crawler. I bought my first narrowboat from Stoke on Trent in 1986. Then in 1998 I got the chance to buy a fine replica Dutch Barge, Saul Trader, and begin to plan a series of voyages from Gloucester, across the English Channel to France, Holland and Belgium. My books are the stories behind our voyages, and whether you’re an established enthusiast, a boater or an armchair follower I hope you will find some pleasure and enjoyment from my ramblings. The thrill and relaxation was short lived as on a more desolate stretch of the canal we stopped moving forward, although oddly I could go back wards 20 foot or so and the same forward. Ten minutes leaning over the side and we still had a prop connected so we must be snagged. If at any time I had looked forward, I would realise we were missing something, The PULPIT !! Having removed this for painting, I had just placed it back on the deck with a length of rope coiled up just to hold it. Amazingly it made one of the best performing anchors I have ever known! Shorts on and in we go to retrieve it from around a sunken tree branch. Luckily nothing more was damaged than my pride.

The thrill and relaxation was short lived as on a more desolate stretch of the canal we stopped moving forward, although oddly I could go back wards 20 foot or so and the same forward. Ten minutes leaning over the side and we still had a prop connected so we must be snagged. If at any time I had looked forward, I would realise we were missing something, The PULPIT !! Having removed this for painting, I had just placed it back on the deck with a length of rope coiled up just to hold it. Amazingly it made one of the best performing anchors I have ever known! Shorts on and in we go to retrieve it from around a sunken tree branch. Luckily nothing more was damaged than my pride.