NOTE FROM AUTHOR

"Crick Wharf is an immaculate example of a regency wharf that was purchased by developers in spring last year. They apparently had every intention of waltzing in and knocking it down, but I got wind of it, alerted the various history gangs and managed to rummage out enough of its story that the developers couldn't use the "not of any historical interest" excuse to whop it with a bulldozer!"

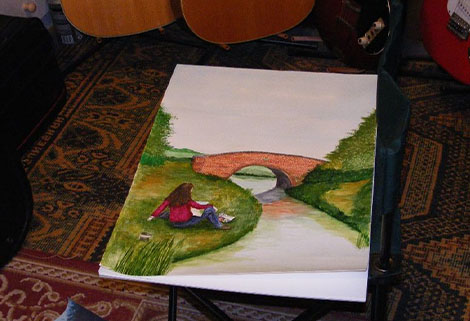

Crick Wharf showing The Moorings café before it was sold...

On the 9th August 1814, 3 boats, and their boatmen, had been scrubbed to within an inch of their lives and now sat waiting at Crick Wharf.

A rather harassed clerk had overseen the lead boat being festooned with flags and flowers, and watched a band carefully wedging themselves into the front end, before drumming it into the boatmen to be seen and not heard.

The newspapers describe the passengers for the lead boat as “a large assemblage of beauty and fashion” while the others are merely carrying “such ladies and gentlemen who chose to be of the party,” but we can safely assume that they were all politely bred enough to carefully ignore the fact that they were joining the opening journey of the Grand Union Canal at what was, in essence, a building site.

It was probably a practical decision. Although the newspapers tell of the journey beginning at Long Buckby, it wouldn't have been possible to do the whole journey in one day and still have time for the lunch at Welford junction and a slap-up meal at Market Harborough.

So the train of boats set out and pretended that Crick hadn't been there. Probably by accident, they gained a pair of flyboats as a rear-guard to Welford junction, who finally managed to overtake when the party boats stopped for lunch.

As soon as the posh people had left, the builders carried on. It's hard to know exactly what was completed when the trio of boats passed by, but it is likely that the small wharf office was completed and at least the foundations built for the T-shaped wharfinger's house. There would also be 3 lime kilns, a brick clamp and at least one cottage being built, as well as the stable, the pigsty, the warehouse, the stables and the outbuildings.

The house was finished by December, when the company advertised both Crick and Husbands Bosworth wharves for immediate lease; Crick is described as “a new and substantial House, Coal-Sheds, and about one Acre of Ground.” , which suggests that the warehouse and stables weren’t completed. They were done by March 1815, when the Northampton Mercury advertised that an auction would be held on the site and all the leftovers from the tunnel construction would be sold. It is fair to assume that the company wouldn't be selling bricks if they still needed them to complete their wharf.

The first wharfinger was John Foster, who introduces himself in 1816 advertising that he has both Crick and Husbands Bosworth wharf, and an ample supply of “coal, cokes, limes etc” and “excellent warehouses” for the storage of goods.

John Foster appears to have got his position at the wharf largely thanks to being one the two brickyards that produced all the bricks for the tunnel, Foster’s brickyard being sited just over the road from the wharf. He was, by all accounts, a well respected man about the village and his narrowboat pair were crewed by local men, who left their families in the village for a week or so at a time to take the boats to Derby and back for coal.

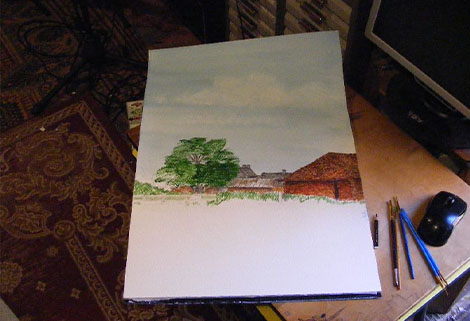

Crick Wharf with the Wharf Inn and outbuildings

When Foster left the wharf for the last time in 1850 destined for his final resting place in the grounds of the Methodist Chapel, the wharf was quickly let out to London shopkeeper Benjamin Rowley and his wife, who appear to be the ones to open up the wharf house as a pub, The Grand Union Inn.

Rowley did not stay all that long, leaving in 1854 to run The Railway Inn in Great Bowden, and he was briefly replaced by William Edmunds, who promptly died.

Christopher Goddard took the reins next, and under his hand we see the wharf clearest for the first time. Goddard had arrived at the village as a groom in the vicars household, and married a local girl. When the wharf became available, he leapt at it and they moved in 1858.

The wharf then was not the peaceful place we see now; iron-shod horses clattered in and out drawing wagons, steam driven fly boats arrived in a shower of steam to bunker up, horse boats glided through, a crane rattled as it lifted mighty blocks of stone from the cargo holds, the 3 lime kilns (sat where the basin is now) and 2 brick kilns (behind the lime kilns) billowed smoke to the sky, and the voices of men, women and children pierced over the din to shout instructions and call greetings.

The Goddard’s were enterprising and invested. Mary, his wife, set up a successful laundry sideline for boaters' washing and Christopher earned the pub a good reputation in dining and hospitality.

Good enough, in fact, that the company appears to have been quite prepared to have to hire another wharfinger so he could concentrate more on the pub.

But this prosperity couldn’t last. Trade depended heavily on the canal being open and the company had been neglecting its maintenance, resulting in closures and stoppage. By October 1866, the Goddard’s were done. They sold everything; “painted French, iron, and other bedsteads; straw paillasses, painted dressing tables and washhand stands, 8-day clock oak case, mahogany and deal 1-leaf and round tables, oak corner cupboard, parlour carpet, 11 and one arm Windsor chairs, six oak-framed ditto, hair seated ; six and one arm rush-seated ditto, brass bottlejack, brass, iron, steel, and other fenders; sets of fire irons, 12 iron spittoons, moderator and other lamps, clothes horses, two buckets, quantity of jugs, mugs, and glasses, 24-gallon copper furnace, oven and ironing stove grate, four club room tables, with tressels and forms; stone hammers, lime hooks and drag, quantity of faggots and coal slack. Also a useful cart horse, coal cart, sow and five pigs, fowls, and other effects” and left the wharf.

In spring 1867, the maintenance boats were deep in the drippy darkness patching up the tired tunnel by the flickering light of candles when there was an ominous rumble and the a chunk of the roof fell down nearly burying them alive.

Unlike previous little mishaps, when canal traffic had been able to creep cautiously by, this time the line was shut. Although it was only closed completely for about 2 months, the ramifications were severe. Cargo was rerouted or lost altogether, and the intermittent stoppages meant that boats timed their journeys differently to miss out Crick. Steamers that didn’t stop at all began to take over, and then the company added insult to injury by raising the rent.

The company moved Thomas and Ann Browning into Crick from Husbands Bosworth as soon as they could. These were seasoned wharfingers with excellent credentials, and perhaps the company hoped they could turn the fortunes of Crick around.

But the wharf was quieting off. The biggest excitements came in 1874 when it was reported that Browning had an apparently never ending crop of oats, and in 1880 (under the new wharfinger, Browning's nephew, Page Osbourne) when a passing policeman saw two lads sneak out of the back door of the house and wriggle through a hedge. He gave chase, bringing down the first as he was throwing apples away, and easily pouncing on the second who was having difficulty making an escape because his trousers were stuffed with onions.

Osbourne left in 1884 and was replaced with Thomas Groom, and then by George Coleman and his mother. Coleman seems to have supplemented his income hiring out his horses, but stopped when after his pony threw the boy riding it and broke both his arms. After Coleman’s unexpected death in 1894, his mother Emma carried on the wharf with the help of Walter Crofts, who she hired to manage the wharf side of business.

Emma appears to have had no love for the boaters who she served, taking one to court after his narrowboat damaged her rowing boat that she’d left sticking into the canal channel, and having another one charged for pinching a leather strap strap to replace his own broken one.

Walter Crofts with his wife and daughter in 1906

On her death in 1904, Walter Crofts quietly and competently carried on the wharf. He proudly posed in 1906 for the camera in front of the inn beside his wife, his daughter and his sister in law.

His tenure saw the wharf welcome its first real pleasure boating in the form of Sunday School excursions, during which 150 or so children and their keepers were stuffed into specially cleaned out boats and taken on a return trip to Hemplow for a picnic.

Crofts death in 1933 signalled the beginning of the end for the wharf. Briefly going to Albert Ernest Foster Sabin, the last wharfinger is Alan Godfrey Ward, who was there barely less than a year when when Superintendent Lawrence opposed granting the Grand Union Inn its license renewal on the grounds of redundancy.

He seems to have had it in for the wharf for some reason, explicitly telling Ward not to bother when he took the license because objections would be made at the renewal. At the renewal he skews the facts, citing four license transfers in 12 months as evidence of the wharf’s futility, but failing to mention the first two were due to death. He cited the wharfs trade between October to March was poor, and that it only used 162 gallons of beer, 3 bottles of sherry, 7 bottles of port, 6 bottles of whiskey and 1 bottle of gin in the time period, but failed to mention that winter stoppages had affected trade.

Despite the best efforts of Ward’s solicitors, Superintendent Lawrence got his wish. On the 29th April, 1935, the final refusal was issued and the Grand Union Inn closed for good.

The company tried to fight the decision, but the wharf sat empty until after the second world war, when they rented the house out to maintenance man, Charles Smith. He wasn’t there long, leaving when the canals were nationalised, and in 1950 the wharf burst into life once more when British Waterways moved their concrete piling manufacture to the site, and moved in Reg Fuller as the foreman.

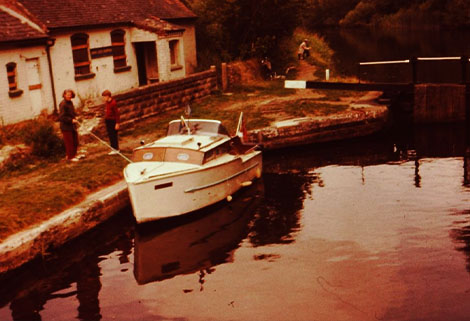

Crick Wharf in 1961

Around 1960 BW decided to move the production to Hillmorton. Reg and his wife remained in the wharfingers house, and the outbuildings were once again rented out; Ted the carpenter set up in the stables and was character enough that it was his name that adorned the side of the restaurant; ‘Edwards’.

Reg and his wife left in 1971, having been witness to the wharf welcome back working boats of a kind - hire boats. ‘Just Boats’ operated from the site from 1969 with varying success.

The site was approaching its final transformation into the site we see today. In 1979, the last traces of the lime kilns were obliterated by the creation of the basin, and the pig sties and small outbuildings adjoining the wharfingers house were flattened to accommodate the spoil heap. In 1986 the warehouse was transformed into a restaurant, and there were plans to make the wharfinger's house into something akin to a hotel, but the latter never came to pass and it remains empty to this day.

In spring 2020, with Coronavirus forcing the wharf restaurant to close its doors, Canal and River Trust quietly sold the site to Aspect for property development, and nearly 200 years of unique history, in a shell nigh on unchanged since the John Foster moved in, now rests on the whims of a housing estate builder. It’s future is uncertain, but at least it’s stories are now heard once more.

“Now, maybe” he thought, as he looked across the river “Maybe there is some rule, or byelaw that says that I should not be here at all. Somewhere in some dusty office is a book in which is written an edict proclaiming that I should not do what I am about to do, however, in the absence of anybody to inform me of the fact or enforce said edict, I shall carry on and see what happens.”

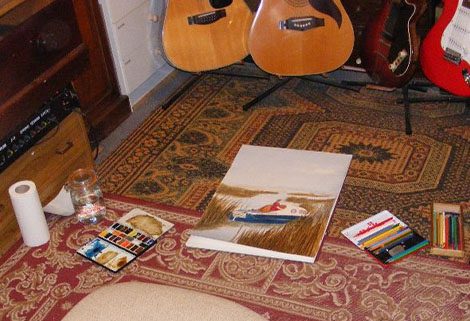

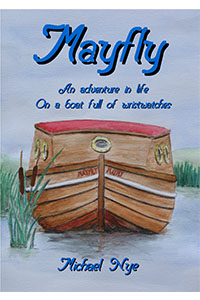

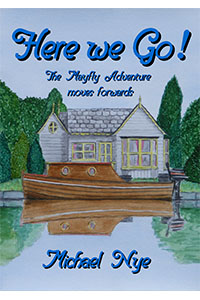

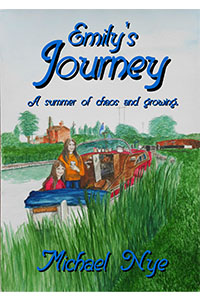

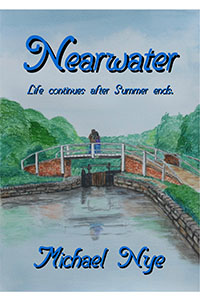

“Now, maybe” he thought, as he looked across the river “Maybe there is some rule, or byelaw that says that I should not be here at all. Somewhere in some dusty office is a book in which is written an edict proclaiming that I should not do what I am about to do, however, in the absence of anybody to inform me of the fact or enforce said edict, I shall carry on and see what happens.” They do say that everyone has a book in them but, when I wrote that first paragraph about eleven years ago I didn’t even think there was a book. A short story perhaps, but not a book, and certainly not eight of the things! Jim and Amanda simply won’t either fade or go away. Their adventure is ongoing as I am working to get this year’s book “The Mayfly Children” into print. It’s hard to think that the main characters (who are both older than me) are still going strong. Jim couldn’t possibly have known where the adventure would go, mainly because I as a writer had no idea whatsoever. I just wrote bits as the ideas came into my head. New people arrived and were written into the plot, all of which was held in my memory until I made a mess of things which I then proceeded to unravel.

They do say that everyone has a book in them but, when I wrote that first paragraph about eleven years ago I didn’t even think there was a book. A short story perhaps, but not a book, and certainly not eight of the things! Jim and Amanda simply won’t either fade or go away. Their adventure is ongoing as I am working to get this year’s book “The Mayfly Children” into print. It’s hard to think that the main characters (who are both older than me) are still going strong. Jim couldn’t possibly have known where the adventure would go, mainly because I as a writer had no idea whatsoever. I just wrote bits as the ideas came into my head. New people arrived and were written into the plot, all of which was held in my memory until I made a mess of things which I then proceeded to unravel. Whilst all of my stories are fiction, real life does appear in them in places almost as it happened. The only difference is that they happen to someone else and not me.

Whilst all of my stories are fiction, real life does appear in them in places almost as it happened. The only difference is that they happen to someone else and not me. The words spoken by May in “Maze Days” were similar to the words I would have used if I hadn’t bottled them up for fear of appearing stupid or causing offence. You’ll have to read the book to find out what happened after that!

The words spoken by May in “Maze Days” were similar to the words I would have used if I hadn’t bottled them up for fear of appearing stupid or causing offence. You’ll have to read the book to find out what happened after that!

First sort the outboard which, despite the odd run up, occasionally decided not to come out of self-isolation and point blank refused to start.

First sort the outboard which, despite the odd run up, occasionally decided not to come out of self-isolation and point blank refused to start. Tool of the year has to be a rechargeable pressure washer – which made short work of the green slime. I am a big fan of this bio boat cleaner, spray it on leave it to dissolve the grime and rinse off. Obviously the pressure washer found the weak spots in the paint work so a rub down (go steady with this remember all glass fibre boats have a water proof gel coat, or rather did until your belt sander removed it) I have found Hammerite smooth works wonders and in my impatience discovered a trick; sand it off before it goes hard, it fills the sand paper almost immediately but it also fills in any imperfections (almost like polishing it) and goes rock hard. The pressure washer is such fun that I did the outboard (which is why it struggled to start - got a bit damp!!), bilges, shower room and even the loo and especially the moss in the window frames.

Tool of the year has to be a rechargeable pressure washer – which made short work of the green slime. I am a big fan of this bio boat cleaner, spray it on leave it to dissolve the grime and rinse off. Obviously the pressure washer found the weak spots in the paint work so a rub down (go steady with this remember all glass fibre boats have a water proof gel coat, or rather did until your belt sander removed it) I have found Hammerite smooth works wonders and in my impatience discovered a trick; sand it off before it goes hard, it fills the sand paper almost immediately but it also fills in any imperfections (almost like polishing it) and goes rock hard. The pressure washer is such fun that I did the outboard (which is why it struggled to start - got a bit damp!!), bilges, shower room and even the loo and especially the moss in the window frames. It is estimated that roughly ninety percent of the world’s goods are transported by sea, with over seventy percent as containerized cargo.

It is estimated that roughly ninety percent of the world’s goods are transported by sea, with over seventy percent as containerized cargo.

Our volunteer team in South Tees received an emergency call on Easter Sunday from an inbound vessel with a single toothbrush between a crew of 17. The team sprang into action, unlocking the centre, stripping the shelves of toothbrushes and allied toiletries. What started with a toothbrush has now grown. “Our team started to make up welfare packs of toiletries, biscuits and chocolates – all duly quarantined and safely delivered to the gangways,” explains volunteer, Alexe Finlay.

Our volunteer team in South Tees received an emergency call on Easter Sunday from an inbound vessel with a single toothbrush between a crew of 17. The team sprang into action, unlocking the centre, stripping the shelves of toothbrushes and allied toiletries. What started with a toothbrush has now grown. “Our team started to make up welfare packs of toiletries, biscuits and chocolates – all duly quarantined and safely delivered to the gangways,” explains volunteer, Alexe Finlay.

Making boats and owning boats is a thing of passion. Boating aficionados around the world are always looking for the new and interesting trends that are reshaping their industry, as well as opportunities to get better gear, take better care of their boats, and even find new makes and models to invest in. From the business side, though, there is no denying that the boating industry is a highly competitive field.

Making boats and owning boats is a thing of passion. Boating aficionados around the world are always looking for the new and interesting trends that are reshaping their industry, as well as opportunities to get better gear, take better care of their boats, and even find new makes and models to invest in. From the business side, though, there is no denying that the boating industry is a highly competitive field. Technology is reshaping every industry in the world, and that includes boat manufacturing and design.

Technology is reshaping every industry in the world, and that includes boat manufacturing and design. For manufacturers and buyers, safety is becoming the most important factor. Manufacturers know that having a

For manufacturers and buyers, safety is becoming the most important factor. Manufacturers know that having a

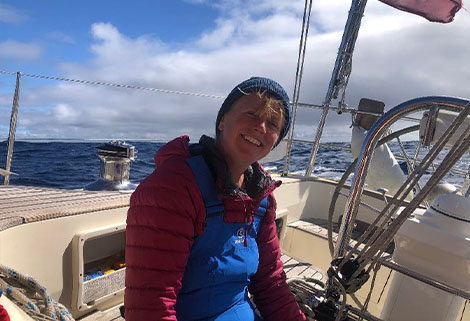

As I am writing this on the last weekend in January, I have made it across to the boat just to pump her out and check any damage from the numerous winter storms which the met officer have now given cute names to possibly in a bid to make them more user friendly.

As I am writing this on the last weekend in January, I have made it across to the boat just to pump her out and check any damage from the numerous winter storms which the met officer have now given cute names to possibly in a bid to make them more user friendly. She was actually intercepted in 2019 mid Atlantic by the ice survey ship HMS Protector who, after checking her for live crew, left her to continue on her way until eventually she was washed up on the Cork coast in southern Ireland 2 years after she first set sail by herself , her hatches still intact-her life boat still in its Davits even the crane survived . Ok from the photographs she could probably do with a lick of paint but she probably needed that before she set sail. Which proves that it is often people that fail first and not the boat.

She was actually intercepted in 2019 mid Atlantic by the ice survey ship HMS Protector who, after checking her for live crew, left her to continue on her way until eventually she was washed up on the Cork coast in southern Ireland 2 years after she first set sail by herself , her hatches still intact-her life boat still in its Davits even the crane survived . Ok from the photographs she could probably do with a lick of paint but she probably needed that before she set sail. Which proves that it is often people that fail first and not the boat. Any way we are on the canal so DT is hardly going to make it to Bristol by herself and if she did sink it would only be in 2 foot of water . So what did we find after leaving her since Christmas ? She had about a bucket full of water in the bilge, her canopy was still on , her battery was fully charged thanks to the solar , down below was damp due to condensation but dry bunks and limited mould. She looked amazingly clean due to using that special cleaner that leaves a residue that mould cannot grip on . A quick check on her mooring lines which the hitches had stretched slightly but certainly still tight and after the obligatory sign in on the app it is time to go and leave her to weather it out for another few weeks.

Any way we are on the canal so DT is hardly going to make it to Bristol by herself and if she did sink it would only be in 2 foot of water . So what did we find after leaving her since Christmas ? She had about a bucket full of water in the bilge, her canopy was still on , her battery was fully charged thanks to the solar , down below was damp due to condensation but dry bunks and limited mould. She looked amazingly clean due to using that special cleaner that leaves a residue that mould cannot grip on . A quick check on her mooring lines which the hitches had stretched slightly but certainly still tight and after the obligatory sign in on the app it is time to go and leave her to weather it out for another few weeks.

In 2012, the Trust sent The Diana on an 82-mile canal and river journey to provide accommodation near the Olympic Stadium for disabled visitors from throughout the UK. During the voyage, various Rotary Clubs along the Kennet and Avon Canal crewed the boat and provided day trips to local groups of people with special needs.

In 2012, the Trust sent The Diana on an 82-mile canal and river journey to provide accommodation near the Olympic Stadium for disabled visitors from throughout the UK. During the voyage, various Rotary Clubs along the Kennet and Avon Canal crewed the boat and provided day trips to local groups of people with special needs.