safety certificate?

wot's one of them then?

In the spring of 1969, Lady Jena, the family’s 16ft plywood cabin cruiser, sank due to a plastic lid working its way through a piece of rather soft plywood.

In the spring of 1969, Lady Jena, the family’s 16ft plywood cabin cruiser, sank due to a plastic lid working its way through a piece of rather soft plywood.

There was some panic but a petrol powered pump was hired from Turk and sons, the boat refloated and the hole temporarily blocked with greasy rags. It was then towed down to their boatyard where it was lifted from the river whilst Mum and Dad had a proper barney with the insurance company who had said that the sinking was due to a latent defect in the hull. Mum and Dad had another viewpoint and eventually managed to exit the argument with dignity. An “ex gratia” payment approximately equal to the claim was paid leaving my parents ready and willing to clean up and repaint the boat.

Dad replaced the offending plywood sheet (comprising about a quarter of one side) and the boat was painted out in a striking blue and cream livery. In order to gain internal space, the rather less than reliable Albin 10 horsepower motor was sold to Turks and an outboard was bought to fit on the assemblage of steel brackets and wood that Dad had neatly fitted to the stern.

All was looking great.

We would go on holiday as usual, this time powered by an British built single cylinder 4 stroke, 4 horsepower outboard motor which even had a generator so we wouldn’t have to avoid use of the lighting. When I saw it for the first time I had a few misgivings despite my lack of engineering experience. The thing looked like a lawnmower engine on top of a pipe. When started it even sounded like a petrol lawnmower, probably because the same motor was used on some models of Flymo hover mowers.

When we set off all seemed well until, at the first lock, the control cables flew off the motor and Dad had to lean over the back and find the piece of bent metal that passed for a gear lever before we hit something.

Whilst in the lock, he clipped them back into place and we headed off upriver with a nice graunch as forward gear was engaged by pulling the remote lever back (For no real reason it worked the other way round) .

After about twenty minutes, the fuel pump pulled in a nice air bubble and the motor stopped dead. I was asked to lift the remote tank above the outboard. The tank looked like a recycled catering cooking oil can that had been sprayed white. Mainly because it was exactly that. Once we were under way again, Mum found some string and we proceeded with the tank hanging for as long as we had the motor.

Partly because of the servicing requirements of our new power unit, we decided to go onto the Oxford Canal via the Sheepwash channel. That took us through some rather weedy water which proved conclusively that the “weedless” propeller was anything but. That discovery was eclipsed by the experience of the electrically powered lift bridge near Wolvercote. Dad sounded the horn as required. Nothing happened so we reversed to hold position in the water.

Partly because of the servicing requirements of our new power unit, we decided to go onto the Oxford Canal via the Sheepwash channel. That took us through some rather weedy water which proved conclusively that the “weedless” propeller was anything but. That discovery was eclipsed by the experience of the electrically powered lift bridge near Wolvercote. Dad sounded the horn as required. Nothing happened so we reversed to hold position in the water.

Eventually, with Dad on the towpath, ready to head to the factory gatehouse, someone opened the bridge. Mum then put the motor into gear, only to find that it wouldn’t go into gear. A novel feature of the gearbox was that, due to poor design, the prop shaft moved back and forward when the gears were selected, leaving an inch or so gap between the back of the prop and the gearbox. This was now packed with chopped up weeds and wouldn’t move. We hand towed the boat through the bridge and Dad flipped the motor up, spilling petrol on himself, ready to attack the jammed weed whilst he smoked a cigarette.

We were ready to continue again, which we did for another mile. There followed a tooth jarring screech as the Aspera (not Villiers as advertised) motor seized up solid, never to run again. It was an ex outboard, dead as a doorpost and sworn at by the whole family. We continued by hand towing until we got to somewhere with a phone. That place being a pub called “The Wise Alderman,” the landlord of which had a pint ready for Dad as he stepped in.

We were ready to continue again, which we did for another mile. There followed a tooth jarring screech as the Aspera (not Villiers as advertised) motor seized up solid, never to run again. It was an ex outboard, dead as a doorpost and sworn at by the whole family. We continued by hand towing until we got to somewhere with a phone. That place being a pub called “The Wise Alderman,” the landlord of which had a pint ready for Dad as he stepped in.

“You’ll be needing this before you do anything,” he said.

Quite how the landlord knew that, I have no idea but it was certainly welcome. The landlord allowed us to moor until we’d sorted out the motor issue, which took a total of three days.

The mixture of petrol, smoking, Methylated spirit stoves and slowly decomposing plywood would strike horror into the heart of may boat inspectors these days but such Heath Robinson boat fit outs were commonplace on the waterways of the mid to late sixties.

The mixture of petrol, smoking, Methylated spirit stoves and slowly decomposing plywood would strike horror into the heart of may boat inspectors these days but such Heath Robinson boat fit outs were commonplace on the waterways of the mid to late sixties.

Several were built from ex W.D. bridging pontoons, and I remember one stern-wheeler that had the engine of an Austin Mini sat high up next to the cabin, attached by a long motorcycle chain to the paddle. The original gearbox and clutch pedal was retained, and the steerer changed gear as the craft progressed.

The superstructure of another pontoon was made of the recycled front of a Birmingham boutique. This was powered by a 4 hp British Seagull outboard. This truly couldn’t be ignored in my writing and first appears in “Mayfly” as “Chrysophyllax Diver” - a name I pinched from a severely holed and very poorly made plywood dinghy that I saw being slowly incinerated on a bonfire near the River Wey.

The superstructure of another pontoon was made of the recycled front of a Birmingham boutique. This was powered by a 4 hp British Seagull outboard. This truly couldn’t be ignored in my writing and first appears in “Mayfly” as “Chrysophyllax Diver” - a name I pinched from a severely holed and very poorly made plywood dinghy that I saw being slowly incinerated on a bonfire near the River Wey.

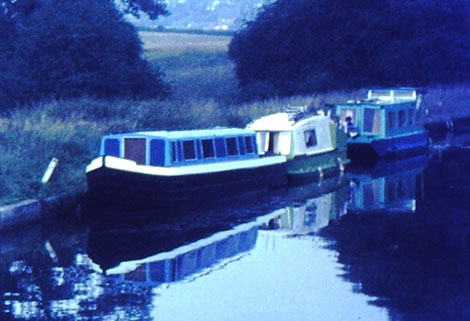

I’ve included some photos of before and after the sinking, together with some incidental shots of the weird and “wonderful” adaptions of craft that flourished before the days when it was deemed wise not to have holidays on boats that varied in safety between tinderboxes and small bombs. Them were the days weren’t they. I guess I survived it all though!