self sufficiency

As summer arrives, the wooding season ends. Tradition says that now is the time for gathering next season's firewood for chopping and stacking, giving it ample time to cure. But as far as burning to keep warm goes, we're out of the woods, so to speak.

It's just as well, really. Lethargy tends to sink in as the leaves appear and the sap starts rising. After six months of finding, sawing and stacking (warming me not twice, according to Thoreau's aphorism, but more like four times – to be fair to him, he recognised this himself but thought twice sounded pithier), the weather improves, and the dead wood gets harder to spot in the growth. I start to struggle. Recently, having nothing to burn on a couple of cool and damp mornings, being near a town, I resorted to buying some of those re-constituted logs from the supermarket. A fiver for a pack of twelve.

The shame.

And me, a hardened scavenger. I haven't paid for heating in over three years. It pained me. But even though all we needed was a mere fraction of the amount I'd collect through winter, taking barely a jot of energy, I just couldn't be arsed.

After we moved onto our narrowboat Yongala (don't ask – it's being changed this year) at the end of 2014, wooding was the first activity to give me that satisfied (some may say smug) sense of self-sufficiency familiar to those interested in such things. At first, clueless and fresh from the city, we bought firewood. But the guy who delivered us builders'-bags of logs for £25 brought green wood at the end of our first winter. I smelled the sap as I split them. And they ruined the inside of our stove and flue. Creosote is insidious stuff. So I started looking for my own.

After we moved onto our narrowboat Yongala (don't ask – it's being changed this year) at the end of 2014, wooding was the first activity to give me that satisfied (some may say smug) sense of self-sufficiency familiar to those interested in such things. At first, clueless and fresh from the city, we bought firewood. But the guy who delivered us builders'-bags of logs for £25 brought green wood at the end of our first winter. I smelled the sap as I split them. And they ruined the inside of our stove and flue. Creosote is insidious stuff. So I started looking for my own.

Naturally, self-sufficiency is a big motivation for many who move onto the waterways. It's a hands-on way of life. No distinction but that of capability, is the time-honoured truism. It makes boat life particularly gratifying.

By and large, people have forgotten to do things, instead relying on technology to work for them. The ever-accelerating, blind and voracious consumption of the hurly-burly in our towns and cities, is what most boat people want to escape. Where outdoors is a temporary inconvenience that people have spent years resolving. Where the seasonal shifts, the weather, the patterns of the stars, the direction of the sun (etc.), is all moot.

We've fallen out of accord with nature. Caro (my wife) and I set out to learn how to live in accord with it as much as possible. I wanted to be a nomadic hunter-gatherer, not a settled citizen. I wanted to forage in the autumn hedgerows, and learn to hunt grey squirrel and rabbit (I haven't yet gained the courage to kill for food). I wanted to learn to sit so still for so long that the wildlife would become bold and emerge for me to admire. That is time well spent.

In terms of maximizing our self-sufficiency day-to-day, we have a composting toilet and have invested in solar power. We grow (to re-phrase, Caro grows) a lot of salad stuff. I'd love to have room to grow a lot of vegetables one day. It's the single biggest drawback to living this life.

In terms of maximizing our self-sufficiency day-to-day, we have a composting toilet and have invested in solar power. We grow (to re-phrase, Caro grows) a lot of salad stuff. I'd love to have room to grow a lot of vegetables one day. It's the single biggest drawback to living this life.

An unexpected, and most pleasurable, aspect of the life is having learned how to care for an engine. I didn't want to, but couldn't afford not to. We had a series of engine issues that culminated in its cracking a piston. It had to be hauled out for re-conditioning to the tune of £5k. We were stuck for three months, severely hampering our vision of the life we'd fostered for ourselves. We were helpless and at the mercy of expensive tradesmen (lovely though many we've met are). When it was back in I started paying attention. It's a BMC 1.5, which means temperamental, and high-maintenance, but hardworking. It's not such a complicated beast. Over time I learned how to look after the small things, to give it a basic service, and hoped to avert disaster. A cracked piston is an act of God. I'm glad it happened when it did.

One of the most important lessons was that fortitude is as essential as aptitude. Your outlook in the face of adversity is probably paramount, actually. It's easy to catastrophize and become overwhelmed, sitting in the engine bay, covered in grease and oil, quietly weeping as the rain starts to fall and you don't know what to do. A stoicism is required, and the ability to focus on the next step to the exclusion of all else until necessary.

With the growth of my desire for self-sufficiency I've become a wilful luddite. I distrust technology. The speed of its development and its capacity to distract us, change us, rob us of our instincts, frightens me, frankly. LTC Rolt, in the conclusion to his book 'Narrow Boat' (published in 1944), struck a prophetic note when he wrote that 'we have become so besotted with the idea of the inevitability of scientific progress that we are contemplating plunging even deeper into the mire of mechanised living, in the tragic belief that, despite the evidence of the past one hundred and fifty years, it is still the way to Utopia. In fact, to follow this road is to sacrifice the individuality and creative ability of man on the altar of material prosperity'. Rolt was ahead of his time in numerous ways, but these misgivings show a man after my own heart. Technological advancement does not, contrary to prevailing belief, equate to progress.

With the growth of my desire for self-sufficiency I've become a wilful luddite. I distrust technology. The speed of its development and its capacity to distract us, change us, rob us of our instincts, frightens me, frankly. LTC Rolt, in the conclusion to his book 'Narrow Boat' (published in 1944), struck a prophetic note when he wrote that 'we have become so besotted with the idea of the inevitability of scientific progress that we are contemplating plunging even deeper into the mire of mechanised living, in the tragic belief that, despite the evidence of the past one hundred and fifty years, it is still the way to Utopia. In fact, to follow this road is to sacrifice the individuality and creative ability of man on the altar of material prosperity'. Rolt was ahead of his time in numerous ways, but these misgivings show a man after my own heart. Technological advancement does not, contrary to prevailing belief, equate to progress.

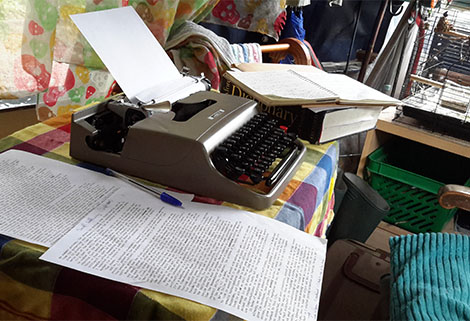

We've enjoyed substituted, where possible, manual power for electric. We only have a basic twelve-volt set-up anyway but I'm liberated from it by my hands. I like having the security of knowing that if something goes wrong, I have a chance of fixing it myself, and that it only takes the effort I expend to achieve results. I use a bow saw for chopping wood. We have a mangle (always evoking fits of nostalgia on the towpath – 'I haven't seen one of them since 1976...'), a sewing-machine, a washing-machine, a drill – all hand-powered. I write on a typewriter. Electronic labour-saving devices mean people forget the tactile pleasure of a task, and there's no pride to be taken in craftsmanship because something did the task for you.

Ultimately, nothing makes one feel freer than casting off and heading down the cut. The feeling of liberation, the adventure, the independence, when you leave a place, is addictive. Itchy-tiller syndrome. One of our greatest pleasures is the solitary and self-contained nature of travel. You simply have to be able to look after yourself in the world.

Ultimately, nothing makes one feel freer than casting off and heading down the cut. The feeling of liberation, the adventure, the independence, when you leave a place, is addictive. Itchy-tiller syndrome. One of our greatest pleasures is the solitary and self-contained nature of travel. You simply have to be able to look after yourself in the world.

Our seasonal cruising pattern is well-established. Winter is on the Llangollen Canal, on the Welsh border, and summer is everywhere else, learning as much as possible. We're at Chester now, but will be somewhere else by the time you read this. It's not for everyone but it's the best place to start to learn some self-sufficiency. It would do us all some good.