tales of the old cut

welcome to Preston Brook Wharf

Preston on the Hill, as it was then known, was a small hamlet of no particular importance sat by the old Roman road to Chester, and it was catapulted into activity in the middle of the 18th century with the coming of the canals and the joining of the Trent and Mersey and Bridgewater canals deep under the soil in the middle of a tunnel.

Preston on the Hill, as it was then known, was a small hamlet of no particular importance sat by the old Roman road to Chester, and it was catapulted into activity in the middle of the 18th century with the coming of the canals and the joining of the Trent and Mersey and Bridgewater canals deep under the soil in the middle of a tunnel.

It was momentous. Cargo from as far south as Cornwall could now be brought up without the risk of having to put to sea, and coal from the north started funnelling down to fuel the furnaces of the Midlands. Indeed, even before they started digging the tunnel there appears to have been a reasonable amount of cargo arriving for transhipment; the Duke had faced stiff opposition from Sir Richard Brooke at Norton Priory blocking the canal to Runcorn and, shrewd operator that he was, he simply outflanked Sir Richard with an over-land transhipment past the Norton blockage in the comfortable knowledge that sooner or later the man would have to capitulate and let him dig his canal.

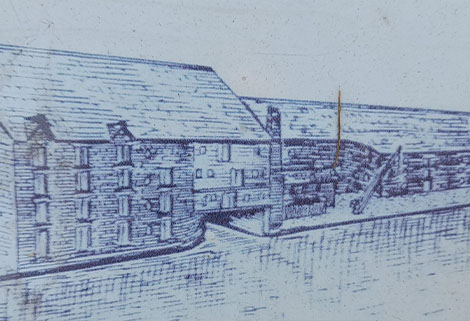

The Trent and Mersey was completed in 1777, so it isn’t beyond probability that the minute the first boat unloaded cargo at the wharf that someone threw up a shed or two to put it in. We certainly know that there was a clay warehouse built by 1785, and the passenger services were long set up by 1788, indicating at least one passenger building.

Passengers were a big part of the early work for the wharf, not least of all with the Duke's own passenger packet boats which shot up and down the Bridgewater behind 2 or 3 horses at a spanking trot. The Dukes boats were classy, sleek vessels with the infamous ‘packet boat blade’ fixed to their bows (ostensibly ready to slice through towlines that weren’t dropped fast enough but realistically more for show,) designed to carry 120 and 80 passengers respectively, but usually grossly overcrowded with lower class passengers clinging to the roof and praying for it not to rain.

Not only did the packet boats carry passengers, but the fly boats running out of Preston Brook did good trade in passengers too; a goodly number were smuggled from boat to boat with the money going straight into the crew's pockets, but also some legitimately booked for travel. The most famous canal passenger the wharf is perhaps associated with is none other than the unfortunate Christina Collins, who boarded the Pickford’s flyboat bound for destiny right on our very own quayside in 1839.

By the time of the railways, the passengers were fading away, but cargo was far from gone. A boat due in at Preston Brook Wharf could be arriving either side of the canal on a stretch of land nearly a mile long.

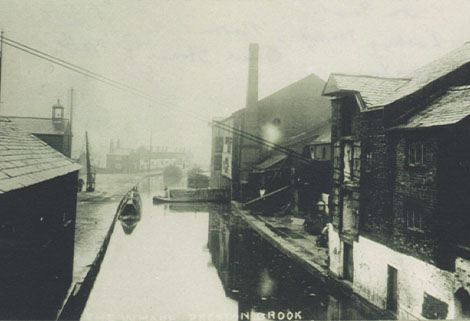

Stables capable of hosting 40 or more horses stretched from by the Norton Junction to opposite a warehouse known as “The Dandy” (sited roughly where Midland Chandlers now stands), a company fire-engine was housed in its very own garage adjacent to a stretch of wharfmen’s cottages and a boatman’s hostel. The towpath was crowded out with cranes belonging to a small warehouse (nicknamed the Bell warehouse owing to the timing bell hung in its roof) before coming to a dead end at the door of an agent's office, while on the off-side the mishmash of mighty warehousing and offices (by now collectively known as the Preston Sheds) bustled around an engine house that plumed steam all day and night to power the cranes and machines.

Through the bridge and past the toll house, boats could be called to the railway departments on one side or the flour warehouse (now known as the Stafford warehouse because of its railway connection) on the other before stopping to be gauged so they could carry on to the tunnel.

A boater stopping at Preston Brook could avail themselves of the Floating Chapel tied near the junction, get their horse shod by a farrier and checked by a vet and send their child for an afternoon of schooling. There were also the usual boaters facilities; houses that took in boatmen’s laundry, ropemakers, harness fitters, shops and a pub.

The wharf’s fortunes began to wane by the first world war but carried on fairly steady trade until the 1930’s, when some of the buildings were knocked down to make way for the widening of the Chester road and they took away her steam engine.

It may even have been this loss of the mechanical power for hoists and pulleys that meant the site fell silent, with trade going round the junction to the Norton Warehouses instead. A brief resurrection of wharfage in the second world war apparently saw Lard being stored on site, but then all fell silent until the demolition teams moved in and flattened nearly 200 years worth of history in just a couple of months.

In 1971 the M56 motorway roared across the landscape and shortly afterwards the wharf came back to life as the home of hire boats belonging to Claymoor Navigation. Claymoor held the site for nearly half a century, before it fell silent once again.

But now, under the idiosyncratic care of yours truly, the wharf is waking up again, ready to tell new stories as well old.

Check out the website!