tales of the old cut

webbs of the wharf

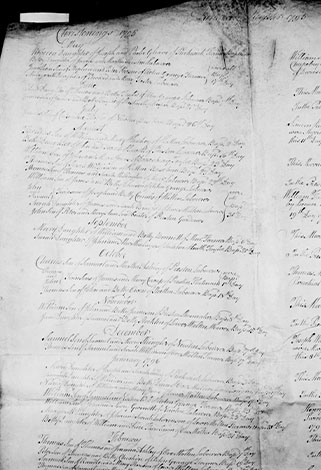

Our story starts with the birth of a baby boy on the outskirts of Norton Estate before the Bridgewater canal was even built. The year was 1759, and Samuel Webb would grow up to become a farmer in his own right, moving only a mile or so from his birthplace to the little township of Acton Grange. While he was still a young man, he witnessed the clash of wills, infamously described as “The battle of Norton”, between Richard Brook, owner of the Norton estate where he was born, and the formidable Duke of Bridgewater over the route of the canal. Perhaps, as his father appears to be a worker for Sir Richard, he was even roped in to the various prevention schemes Sir Richard put forward.

Samuel married a Runcorn girl and the first of at least 8 children arrived in 1786. By now the canal was open from Manchester to Liverpool, and on through to the Midlands via the Trent and Mersey. This was a time of huge changes across the country. As the industrial revolution kicked off thanks to the canals, the agricultural revolution gained speed as well, but the technological advances meant less manpower was needed to work the land. Samuel must have realised quite quickly that there simply wasn’t going to be enough farm to share among his 4 sons.

Samuel married a Runcorn girl and the first of at least 8 children arrived in 1786. By now the canal was open from Manchester to Liverpool, and on through to the Midlands via the Trent and Mersey. This was a time of huge changes across the country. As the industrial revolution kicked off thanks to the canals, the agricultural revolution gained speed as well, but the technological advances meant less manpower was needed to work the land. Samuel must have realised quite quickly that there simply wasn’t going to be enough farm to share among his 4 sons.

One son, also called Samuel, was not ‘normal’, most likely having what we would understand as Autism, but then being described as “inferior”.

It seems as though at least 2 of the sons, and possibly one of the daughters, move a few miles up the road to Great Budworth in search of work. Here we find the young men getting married, and a single woman matching the ‘description’ of a sister falling pregnant out of wedlock.

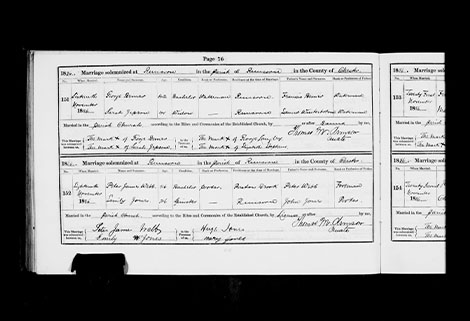

William Webb was only 21 years old when he married Sarah, who was about 30, and what seems to happen next is the couple head to Sarah’s family in Lach Dennis and William takes up work as a canal labourer over at Middlewich. They may have 2 short-lived children during this time, but we can’t track the couple for certain until 1820, when they come onto the Preston Brook radar.

At this time, the wharf was thriving. It was the only true through-route to the Midlands and would remain so until the opening of the Macclesfield canal in 1831. It was shipping hundreds of thousands of tonnes of goods every year, and its warehousing was gradually spreading across the site.

At this time, the wharf was thriving. It was the only true through-route to the Midlands and would remain so until the opening of the Macclesfield canal in 1831. It was shipping hundreds of thousands of tonnes of goods every year, and its warehousing was gradually spreading across the site.

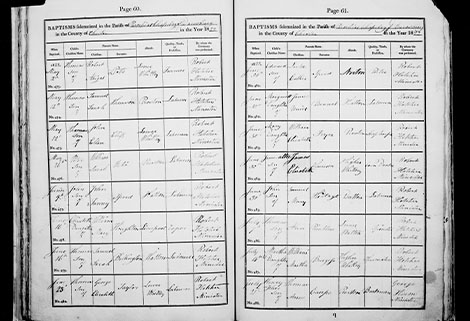

William spends the next decade as a wharf labourer, until in 1830 he appears in the records as a “porter” on the baptism of his youngest son. We lose sight of the Webb family now until the first census of 1841, where William is still a porter and his sons are starting to be absorbed into the hustle and bustle too; eldest boy Peter has become a boatman.

By 1841, William is caring for his older brother Samuel. Samuel is noted as being a labourer, and it wouldn’t be particularly unusual to find handicapped persons employed in simple jobs.

In 1851 we see William at the head of a family well acquainted to the wharf. He is a warehouse porter, along with son Thomas. Youngest son William is now a boatman, and the eldest son, Peter, is “porter for canal carrier.” Peter and his wife Ann have just welcomed their third child to the world and the two older children are staying with their grandfather to give mum a chance to recover. Also in the house is Samuel. Now 62, he is given the description of “inferior from youth,” so it would be reasonable to assume that he is now unable to work. Perhaps the increase in machinery, for the wharf now has a mighty steam engine powering it’s hoists and cranes, has made it too dangerous.

In 1851 we see William at the head of a family well acquainted to the wharf. He is a warehouse porter, along with son Thomas. Youngest son William is now a boatman, and the eldest son, Peter, is “porter for canal carrier.” Peter and his wife Ann have just welcomed their third child to the world and the two older children are staying with their grandfather to give mum a chance to recover. Also in the house is Samuel. Now 62, he is given the description of “inferior from youth,” so it would be reasonable to assume that he is now unable to work. Perhaps the increase in machinery, for the wharf now has a mighty steam engine powering it’s hoists and cranes, has made it too dangerous.

Jumping another ten years to 1861 forward and the family is now firmly entrenched at the wharf. William and his wife live alone with older brother Samuel now, and interestingly William is noted as “Methodist Local Preacher”, as well as a canal carrier’s porter. Next door is his middle son, Thomas, who’s moved off the warehouse floor and into an office; he’s a “canal carrier’s book keeper.” Eldest son Peter is a few doors down and he too has made it into office as a “canal carriers shipping clerk,” while the youngest son, William, is following his father’s footsteps, employed as canal porter and having married a boatwoman some 14 years his senior.

1871 sees William, now 75 but still working as a porter, living with his spinster daughter Mary. Sarah, his wife of 47 years, has died, as has his brother Samuel.

His son Thomas is still a book-keeper and William Jr is now a canal labourer; we could conjecture that his choice of spouse may well have set him apart from his up-and-coming brothers. The eldest son, Peter, is described as a porter but we know it is around this date that he becomes the foreman for the Bridgewater Canal Company at the wharf.

William Webb died in February 1880, aged 84. He had lived to see all three of his sons, and at least 5 of his 7 grandsons join the wharf workforce.

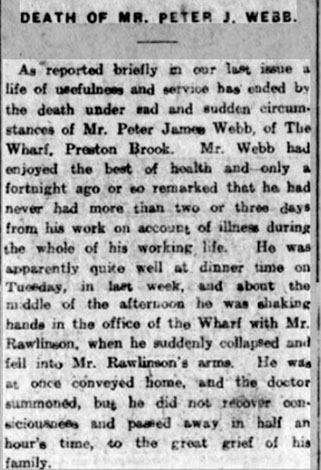

His eldest boy, Peter, perhaps rose the highest. Deeply involved in the Methodist Church like his father, he appears to be pretty much the head-honcho of wharf, the company representative. When he died in 1888 the role was passed to his son, Peter James, who held the role until his sudden death in 1920.

Peter James Webb was, according the Runcorn Weekly News, “…quite well at dinner time… was shaking hands in the office of the wharf with Mr Rawlinson, when he suddenly collapsed into Mr Rawlinson’s arms..” and his death produced a wave of grief, with flowers being sent from the porters and warehousemen, boatmen, office staff, banksmen and even “Runcorn and Preston Brook Spoon Boat no4.”

By 1920 the wharf was winding down, though Webbs still worked at the wharf until the bitter end. By the time the engine was ripped from the site, at least 20 men from 4 generations of that family had worked there, and research is slowly revealing the extended family too.