tales from the old cut 6

diary of a victorian horseboat

I was built sometime in the reign of Victoria, at least 135 years ago, in the Black Country, Birmingham.

I was built sometime in the reign of Victoria, at least 135 years ago, in the Black Country, Birmingham.

The canals were a very different place back then, none of this slowing down to relax and all that they say these days.

The skyline bristled with chimneys and the air was black with smoke. No cars were on the streets and bicycles were still strange contraptions.

Only the fancy boats had engines and they were steam.

I had a horse.

He wasn’t a very good horse but then I was only a maintenance boat, a spoon dredger to be precise. I worked for the Birmingham Canal Navigations Company, number 118 in their fleet, and I worked in the number 2 district around Tipton. My job was to keep the channel deep for the cargo boats, by the simple expedient of what was, in essence, a giant shovel, scooping out silt into my hold.

I had a small cabin then, where the men, usually 3, could have a brew (and occasionally doss down), and in the middle of my hold was a small hand crane, attached to the great iron scoop and its long wooden handle.

I had a small cabin then, where the men, usually 3, could have a brew (and occasionally doss down), and in the middle of my hold was a small hand crane, attached to the great iron scoop and its long wooden handle.

Towards my front end was a winch, which was also attached to the scoop, and when they’d lowered the scoop down into the murky depths, they used the winch to drag it forward into the mud. Then they used the crane to lift the scoop out of the water, and a man used its long wooden handle to guide it so they could dump the contents into my hold.

Each scoopful was about a hundredweight of mud and water, and it went everywhere. My decks were slick with mud, and it reeked in high summer! They had to regularly pump the water out so they could get a full load, which was about 25 tonnes at a time.

Each scoopful was about a hundredweight of mud and water, and it went everywhere. My decks were slick with mud, and it reeked in high summer! They had to regularly pump the water out so they could get a full load, which was about 25 tonnes at a time.

Sometimes there was a fourth man on the bank with another winch, so they could accurately edge me forward bit by bit, but more often than not it was a case of short straws as to who had to haul me forward by hand.

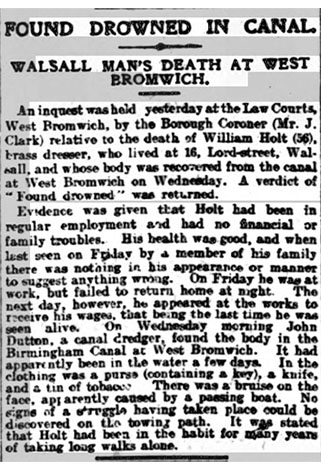

Dredgers sometimes lifted things that were best left lying: guns, knives, sometimes stolen safes and strongboxes (empty of course). Occasionally a dredger would bring a body up, which was never fun for anyone involved and would invariably hold up traffic. It wasn’t unheard of for a body to be quietly slipped back into the water without telling anyone official.

Dredgers sometimes lifted things that were best left lying: guns, knives, sometimes stolen safes and strongboxes (empty of course). Occasionally a dredger would bring a body up, which was never fun for anyone involved and would invariably hold up traffic. It wasn’t unheard of for a body to be quietly slipped back into the water without telling anyone official.

When they’d made a load up, I was towed away and the mud unloaded into spoil heaps, where it could be reloaded back onto a boat to be taken away. Nothing was wasted then; sometimes the spoil was taken to fields out of the city, sometimes to building sites to help level the ground, and sometimes it was taken back to the canal that needed repairing.

No, a spoon dredger’s life was not a glamorous one. The men would swear a lot, and sometimes drink a lot too; that was usually when my cabin got slept in.

I did that until 1937, when they took away my dredging gear and I was put onto general maintenance. During the war I did whatever was needed; sometimes I carried things like lock gates, sometimes I carried bits of Birmingham away that had been blown up by Mr Hitler. Sometimes I even carried cargo for the war effort.

I did that until 1937, when they took away my dredging gear and I was put onto general maintenance. During the war I did whatever was needed; sometimes I carried things like lock gates, sometimes I carried bits of Birmingham away that had been blown up by Mr Hitler. Sometimes I even carried cargo for the war effort.

After the war I carried on doing maintenance. They took my cabin away so I could carry more, and made me smaller, taking some plates out of my middle, so that I could work with a bantam tug. I hauled pilling, scaffolding, bricks. I often worked with a modern dredger, carrying the silt away. I was ignored by everyone and given the frankly ignominious title of a ‘hopper.’

And then, after all that service, more than 100 years dedicated to keeping the canals going, waterways decided they didn’t want me anymore, and that I was “beyond economical repair.”

And then, after all that service, more than 100 years dedicated to keeping the canals going, waterways decided they didn’t want me anymore, and that I was “beyond economical repair.”

I was sold. Retirement beckoned at last, perhaps I would be cut again and turned into a motorboat? Perhaps I would just be broken up?

No.

I am now a cargo boat in my own right. I am still unpowered, but I have a motorboat of my own to take me where I wish, and I have my little cabin back. I will be carrying coal and logs for a fuel boat, and maybe tanks of diesel in the summer. I’ll be taking animal feed, and occasionally animals, the pets of my keeper.

I am now a cargo boat in my own right. I am still unpowered, but I have a motorboat of my own to take me where I wish, and I have my little cabin back. I will be carrying coal and logs for a fuel boat, and maybe tanks of diesel in the summer. I’ll be taking animal feed, and occasionally animals, the pets of my keeper.

Nearly 150 years after I was built, I will still be working. How many other boats can say that?