tales of the old cut

wedding bells

The simple fact that of all people who pop up in my research, 99% of them are dead means I can find myself surrounded by a monosyllabic trail of funeral notes and burial records. The weather as I type this is far too lovely to write about death and destruction, so today we’re looking at weddings.

In today’s world there is a somewhat bizarre concept of ‘jumping over a mopstick’ for a boater getting married, which appears to be a corruption of the idea of jumping over a broomstick to solidify a union that wouldn’t be recognised by the church. This was indeed a real custom among the Romany peoples (as well as within the enslaved peoples), but ‘broomstick marriages’ were not legal and were viewed with scorn by the vast majority of the population, boaters included.

So how did a boater ‘tie the knot’? The answer is actually a little dull; he tied it in the church, like

everyone else.

While they weren’t, as a rule, particularly religious, the idea of getting married in anywhere other than a church was simply dismissed out of hand. Even as late as 1934, a registry office wedding was derided as a poor choice. “They don’t go to church, except to be married, as a rule. But you will never hear of one being married in a registry office, nor of a woman going on another trip after confinement until she has been churched” described one old boater to a journalist for the Express and Star.

Boaters rarely married people not off the canal, in much the same way that miners tended to stay within their communities; it is very hard for an outsider to understand and assimilate into a way of life so alien to them. There were also the practicalities of meeting a potential mate; boaters didn’t really get the chance to meet anyone other than other boaters.

Courtship was conducted mostly on the move, with the young couple having a shy conversation as their boats passed and perhaps going for a little walk together if their boats were at the same wharf at the same time, staying within viewing distance of the young lady’s family of course. Messages and signs could be left for each other on lock beams, scrawled using the grease from the paddle gear. In later years, when bicycles made their way to the boats, a young man might cycle for miles back along the towpath at the end of the working day just to spend half an hour in his young lady’s company.

When the couple were ready for marrying, the young man would approach the company and ask if there was a boat he could have for his own. This was no different to a couple ‘on the bank’ having to organise their own first home, and in fact it was far quicker. Sometimes he might have to wait for a little before a boat was available, but he didn’t need to buy his boat and there was nothing to spend on furniture as the cabin would already be fitted out; all the couple needed was their clothes, some bedding and some crockery.

The process of the wedding was much the same as it was for anyone else when it came to the legal side. As described in 1934, “When the daughter of a boatman agrees to marry the son of another boatman, the two put up Banns at churches at both ends of the canal on which they work. When the two boats meet at the same terminus wharf, the wedding takes place, and it is always attended by a large and picturesque gathering of boat people. The couple have already secured a boat for themselves, and their honeymoon is to a journey to Chester and Ellesmere Port carrying perishable goods.”

The “picturesque” gathering the journalist describes would invariably be based around a pub. There might be a few boaters playing music and as last orders got called at the bar at around 10pm, a few water cans might be filled up with beer to allow the merriment to continue outside.

Invariably, the majority of the wedding party, happy couple included, would be away as usual the following morning. The newly-weds would often be sent to their boat with ribald comments harking back to the ‘bedding ceremony’ of years gone by, with one young man being handed a small cigar by another man: “for affer my lad, for affer” he winked.

Of course what I’ve described here is what you could call the romantic matches, young love. There were far more pragmatic second marriages, where widows and widowers would “make a match” of convenience rather than romance. Either gender of spouse could find themselves bereaved and left with a pair of boats to work and just a few kiddies as crew, and it made far more sense to marry someone in a similar situation.

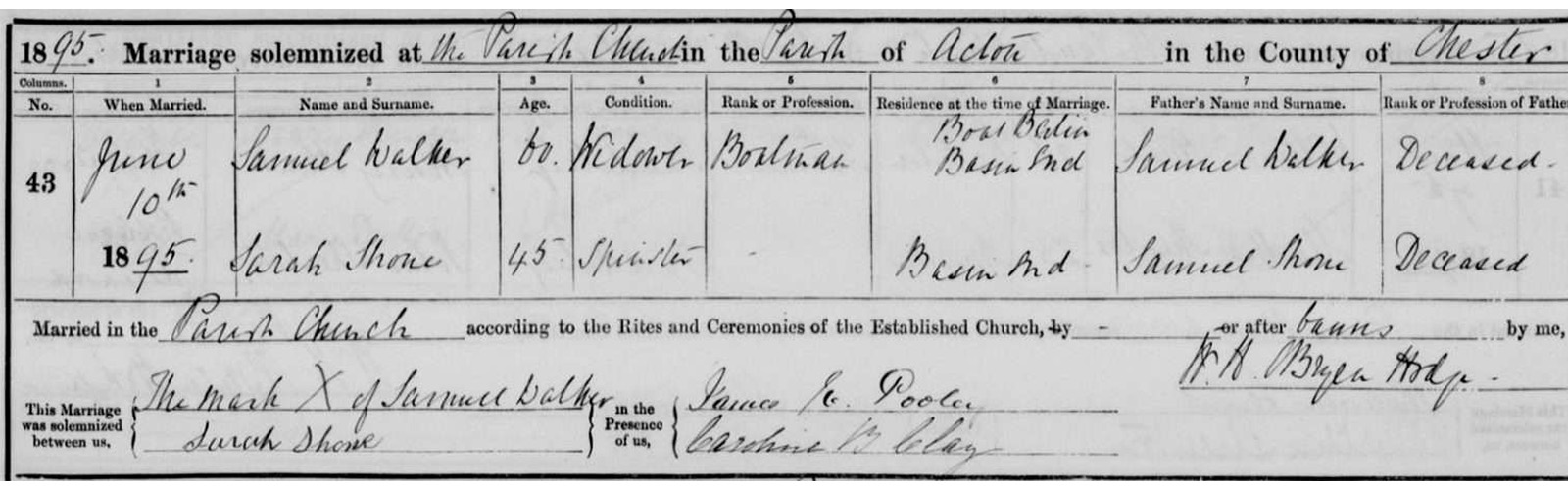

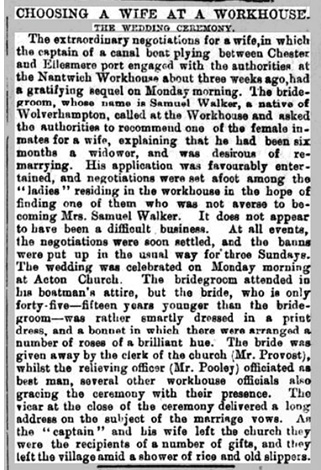

One man took pragmatism to new levels in 1895 when he called in at the Nantwich workhouse and asked if they could recommend any of the women inmates as a potential bride. Born around 1825, Samuel Walker appears to have been working for the Shropshire Union Company, and just 6 months prior to mooring “Berlin” up at Nantwich to go window-shopping for a wife, he’d been at Market Drayton burying his last. The women of the workhouse don’t appear to have been too disconcerted by the prospect of taking up with a boater, and some 50 were brought forward and 45 year old Sarah Shone duly captured the questionable prize.

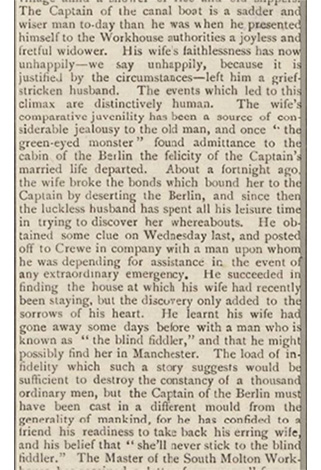

Perhaps unsurprisingly; Sarah very quickly lost interest in working a horseboat with her husband and ran off, allegedly taking up with a blind fiddle player in Manchester. Despite Samuel’s willingness to take back his errant wife, he never saw her again. He must have found someone to work his boat with him though, as he appears to eventually die at Ellesmere Port in 1901.