tales of the old cut

waterloo and the water

I would guess that pretty much everyone is familiar with the battle of Waterloo in 1815, if only as a name synonymous with something this country practically made a sport of in the past - fighting the French.

This battle was the culmination of more than 22 years of on-off fighting, and although all of it had taken place overseas, the ramifications on the home front had been (and would remain) significant; more specifically for our interests, it directly affected the canals and some of it played out here on the wharf at Preston Brook.

The story starts some 30 years before the great bloodbath of Waterloo, in 1780 with the birth of a baby boy named John Pennington.

The Pennington family were fairly typical and reasonably well off; Thomas was farming while his wife, Jane, produced a child every couple of years. The building of the canal and the wharf had improved the local economy and they seem to have had the foresight to realise that the canal was going to be a steady employer for a respectable man, and so made sure their sons had a decent education.

This was a turbulent time for the country, with Britain at war with both America and France, and the country was starting to feel the pinch of funding constant warfare overseas and with the rapidly changing landscape as the industrial revolution started to pick up. We don’t yet know for certain what happened, but in around 1786 Thomas lost his land. Although the local records now record him simply as a labourer, we can be almost certain that it is him that is the ‘Peninton’ working on the wharf as an early porter.

John was apprenticed (possibly to his uncle in nearby Bartington) and learned the trade of smithing, while his brother William went on to be a farm hand, and Thomas went to be a book keeper.

What happens next we may never know the real answer behind. We can conjecture that he was friends with Joseph Bennett, another Preston Brook boy whose father had worked with John’s both on the land and at the wharf (indeed John’s sister Mary had been baptised on the same day as Joseph’s brother William), and Joseph, who had joined up in a few years earlier, had told him how great it was in the army. Or perhaps John got caught out with the King’s shilling at the bottom of a beer mug. Whatever the trigger, on the 27th March 1809, John joined the British army at Manchester and joined the ranks of men in the 16th Light Dragoons, a cavalry regiment.

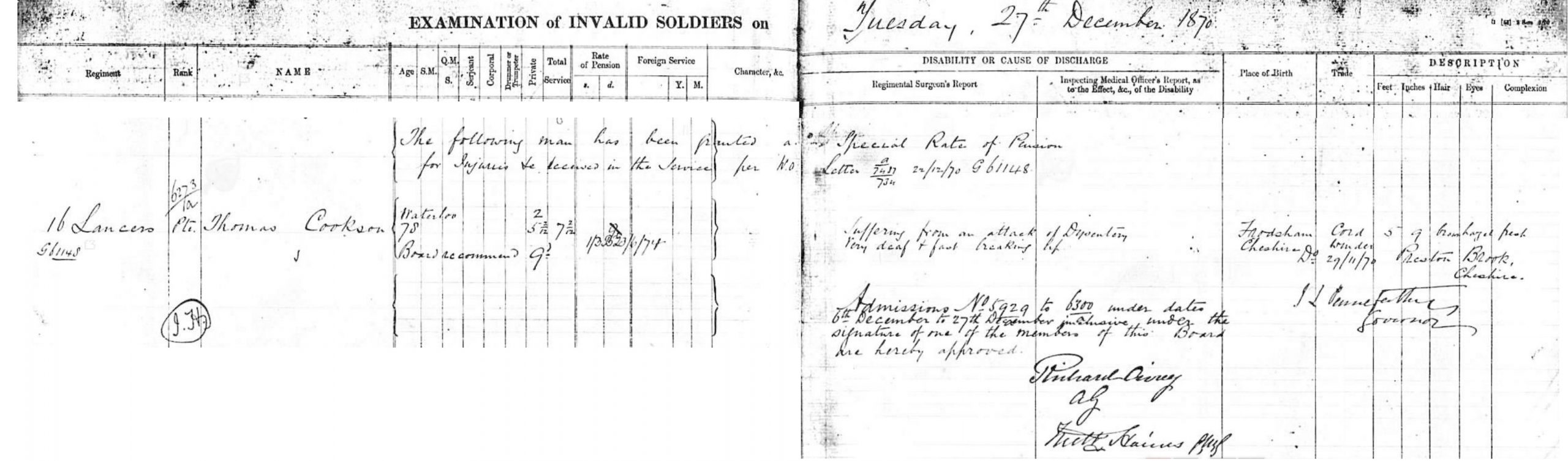

John was a grown man when he joined the army, but Thomas Cookson was a lad of about 18 when he joined the same regiment. As can be seen in Jane Austen’s books; soldiers at this time, with their their smart uniforms and air of adventure about them, had a great deal of sex appeal. Work was becoming a little thin on the ground for unskilled labourers, and food was in short supply too. Thomas, a poor labourer’s son from Frodsham, probably didn’t need much persuading to join the army.

We don’t know for certain how much they knew of each other, but we know that at the Battle of Waterloo itself Private John Pennington was in the Centre Squadron, F Troop under the command of Captain King, and Private Thomas Cookson was in the Left Squadron, A Troop, under Captain Tomkinson.

The gory details of the battle of Waterloo are easily available online for those who wish to be put off their dinner, so I won’t go into them here. For our story here, what is important is that our players came out the other side of it alive, and with all their appendages mostly intact.

Joseph Bennett was forcibly discharged in February 1819 when his regiment disbanded and no one else would take him as he was ‘lame’ on his left foot after it had been crushed. His next move appears to have been to come back to the area and take up as a boatman. We have a description of him: 5’5, with light brown hair, grey eyes, a round face, a ‘sallow’ complexion and a noticeable limp.

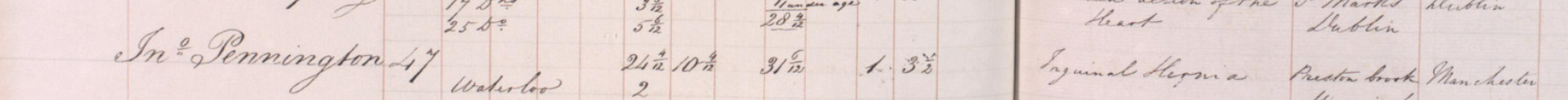

John Pennington stayed with the regiment for another 17 years after the battle, until he was forcibly discharged due to a rather unpleasant inguinal hernia. His movements are difficult to track but it seems he comes back and spends some time with his brother before vanishing off the radar.

Thomas Cookson was the first one to leave the army, and he too comes back to Cheshire a changed man. How he meets her we don’t yet know, but he meets Mary Millington, a canal labourer’s daughter in Moore. Mary is a woman with something of a past herself, with a teenaged son born out of wedlock, but they marry and move to Frodsham just in time for the birth of the first of their 2 sons.

Frodsham didn’t suit the family all that well and, perhaps thanks to a few words in the right place from his former comrade, Thomas gets a job at the wharf as a porter.

The wharf at Preston Brook was a busy, hard working place but, probably due to the large proportion of the workforce being firm Methodists, disabilities were worked around.

Thomas’s hearing grew progressively worse as the years went by until he was almost completely deaf, but he was a competent lip reader so the wharf just kept him where no one could sneak up on him. Even as a frail man of nearly 80 they found him light work to do, coiling ropes and sweeping floors. Interestingly, in 1871 he has Thomas Bennett and his family lodging in his house. It’s not for certain yet but it’s quite plausible that this is the nephew of Joseph Bennett.

With this small selection of veterans sat in such a busy corner of the waterways, it’s no stretch of the imagination to suggest that it was here our final character in the story emerges.

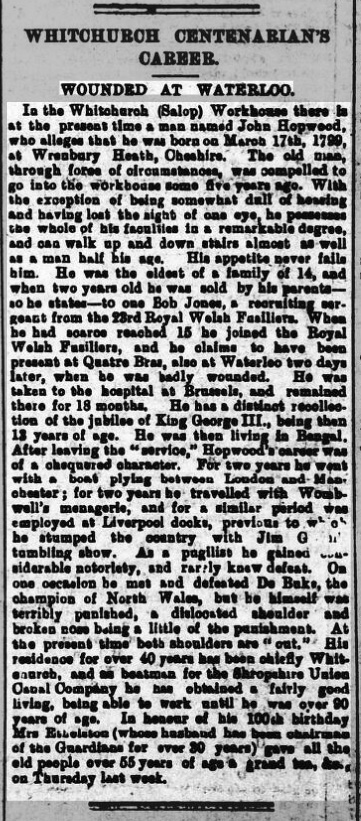

John Hopwood was baptised at about a week old in Wrenbury, appropriately enough on April 1st, and, like many boaters, he’s rather illusive as far as paperwork is concerned. Before 1857, the only probably glimpse we have of him is when he gets accused of stealing someone’s trousers in 1839.

We know that he was an intermittent boater working between London and Manchester on the fly boats, with regular stops off at Preston Brook. In 1857 he was a widower with a 5 year old daughter. Somehow, he catches the eye of a young lady nearly 20 years his junior and that’s when it seems that the stories start.

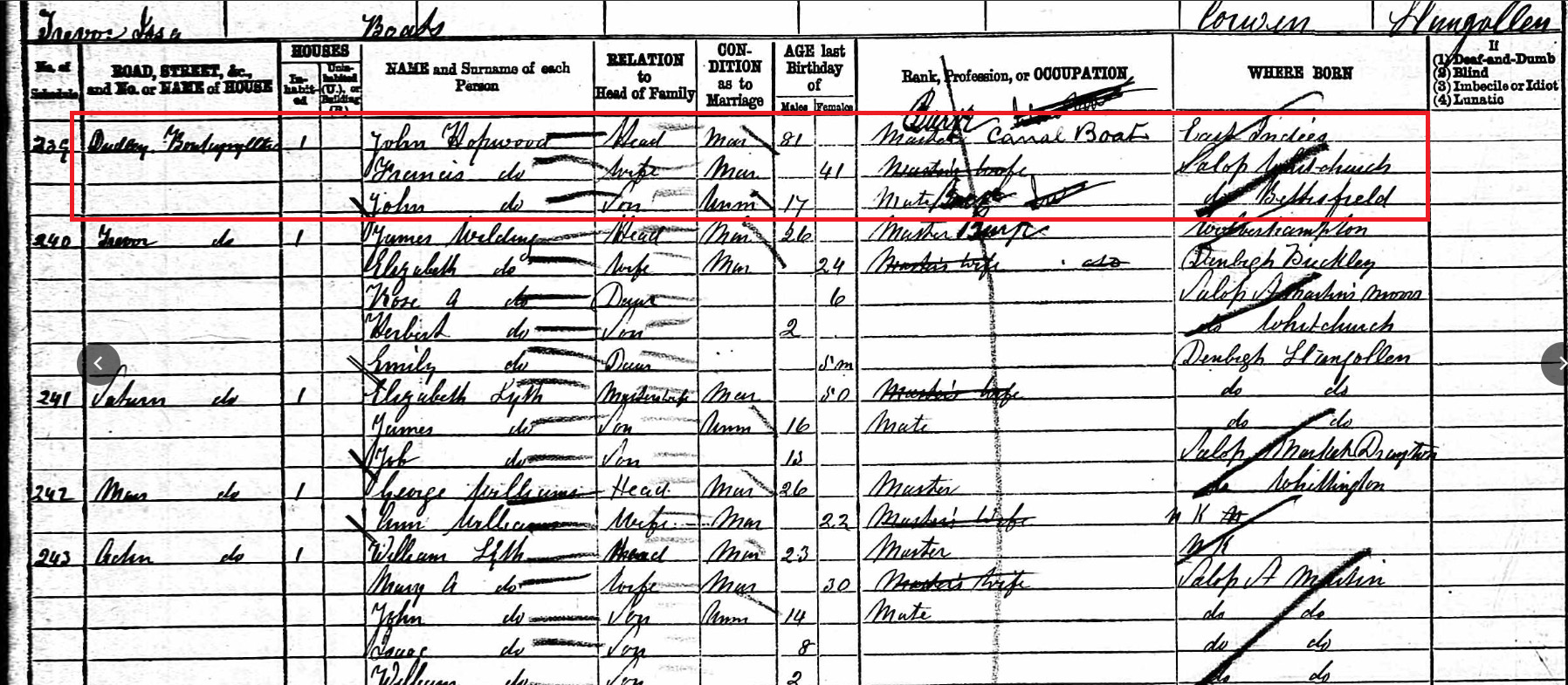

It probably started innocently enough by John telling his new sweetheart he had been a soldier, rather than a trouser thief, but in 1861 Hopwood was working for the Shropshire Union co on “General Havelock” and was insisting to everyone he was a decade older then he actually was so he could back up his claim that he wasn’t just a soldier, but he was also a Waterloo veteran.

A decade later and he’s now on “Pacific”, and moored up at Grindley Brook. His daughter from his first marriage, Elizabeth, had married James Wildey the previous year (the Wildey family would later go on to be written about by ‘Questor’ for the Wolverhampton Express and Star) and it was around then that Hopwood started insisting that he had beaten Deaf Burke, the bare knuckle boxer, and that was how he’d got his broken nose.

In 1881 he’s master of “Dudley” and he’s now telling everyone he was born in Bengal and he’d also spent a few years travelling around with the circus before he came to the boats.

Something happens in the next few years that makes the Shropshire Union Co ask him to give their boat back, and by 1891 his youngest son is working in the Ifton colliery at St Martins to support him and his parents. This son, also called John, must have been having a hard time putting up with his father’s tall tales, not least of all with the none-existent army pension, and on one occasion went out, got blind drunk, refused to leave the pub and ended up being arrested and fined 10 shillings.

Unfortunately for Hopwood, his son died that year and left him with only his wife to support them by doing washing. She then died in 1895, and Hopwood took himself off to the workhouse and carried on embellishing his life story.

Hopwood died in 1900 having convinced everyone, including himself, that he was 101. There were doubters though, with one man noting that it was “people like (Hopwood) that convinced the world of the bargee’s habitual condition of lying”!