return to the scene of the design

architects review old proposals for canal improvements beneath the Westway Flyover

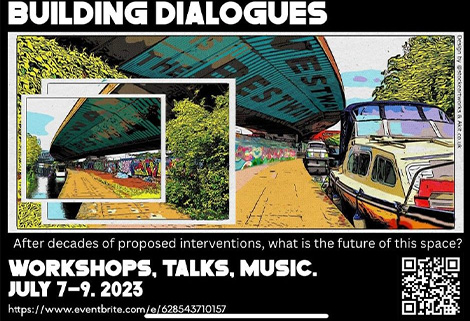

The smooth underbelly of the Westway Highway swings wide over the Grand Union Canal at Westbourne Park, creating a ceiling for the towpath and ½ a dozen canal boats moored below.

For architect Matt Hopkins, it's a sight to behold whenever he cruises into Paddington on his 70’narrowboat. But the breath-taking infrastructure has a troubled history; its construction in 1971 displaced over 3000 North Kensington families. Resulting controversy helped produce much more extensive neighbourhood engagement ahead of similar developments today.

In the half century since, the City of Westminster has responded to the Westway’s intrusion with a number of measures: A sports complex at Shepherd's Bush. Offices and shops at Portobello Road. But at Westbourne Park — where a football pitch length piece of land could support an all-weather market, musical performance, or whatever else the public wants — time stands still.

Why a place with such potential remains a destination for rough sleepers, scofflaw dog walkers, and occasional boaters refitting their interiors is a question I hoped to answer at a discussion Hopkins recently led featuring architects reviewing old proposals to re-imagine the space.

The discussion was part of a weekend program called "Building Dialogues" ̈the latest in a history of interventions for this persistently challenging spot. Besides an architectural discussion there was music, educational workshops and a visioning exercise for boaters and borough representatives. All to demonstrate the variety of programmes the space lends itself to, and which were last seen there during a month-long 2019 London Festival of Architecture installation.

I had been a participant in that, loaning my boat and its full length stage to the team who contributed the winning entry, the ̈Co-Mooring ̈, which for 30,000 pounds attempted to unite land and water, encouraging more and better interaction between boaters and visitors to the canal. Its lofty ideas collided with reality, however, when cyclists objected to its sinuous boardwalk and local hoodlums asked for money to not burn it down.

With more continuity, these might have been valuable learning experiences, except the final stakeholders ́ discussion atop Molly Anna was interrupted, and — with Covid around the corner — never resumed.

¨This place STILL needs love.¨ Architect Sophie Nguyen first drew attention to the canalside opportunities of the Westway with her 2017 LFA project.

A 2019 London Festival of Architecture competition produced the ¨ co-Mooring¨ to encourage more interaction with people on the canal.

Four years later we reviewed the list of 49 companies who had submitted proposals for the 2019 competition. Architectural firms KMBH, Sisters & Tiger, Merritt Houmoeller and Make:Good all had received £500 to further develop concepts to temporarily transform the space. Though none were ultimately selected, all wanted to publicly review their old plans and discuss what might still happen.

The architects sat on chairs sandwiched between a vendor selling samosa chaat and an upright piano wheeled in for the occasion. They joked about their professional lot...submissions for design competitions that never pay the bills...but to which they repeatedly succumb, stubbornly believing that the right mix of ingredients can turn urban blight into community gold.

Asia Grzybowska from Sisters and Tiger had driven the furthest, 5 hours from Cornwall, to discuss why no such alchemy had happened here. In a sterile space animated by graffiti but not a blade of grass she related the story of a garbage strewn median in Oakland, California, and how a surreptitiously installed ceramic Buddha had sparked a metamorphosis. People brought flowers. It became a shrine. Crime fell by 80%.

With sympathetic City of Westminster leaders showing renewed interest in canalside opportunities, could something similar happen here? Community-led, in lieu of major investment?

What user groups could be induced to adopt this space? What changes would inspire a similar transformation as Vietnamese pilgrims had brought to an unloved highway median in Oakland?

Ladbroke Grove’s musical community could play a role, suggested Ben Crockett and Jezmond Farran, musicians who waited to perform on the event ́s floating stage. Local legends Hawkwind, the first space rock band, had played there in the early 70s, demonstrating the enduring appeal of the place, the only covered — and therefore weatherproof — stretch of canal in London.

¨Building Dialogues¨ was funded by the Westway Trust to revive interest in the site.

Boaters, residents and representatives from the City of Westminster share their visions.

Fifty years later, what stymies a design that will transform this space? So that vendors can sell goods, boaters can responsibly dispose of rubbish, cyclists can fix their bikes and no one gets run over?

The chief impediment — the architects concluded — is the site's ́complicated ownership. Each team had had to speculate on what various entities would approve: the Highway Department which owns the overpass, the Canal and River Trust which owns the towpath, Great Western Studios which owns a sliver of land and the City of Westminster which owns the rest.

“The Borough,” Hopkins said on behalf of everyone, “is the only entity that will be here in 300 years. They need to convene the other stakeholders and see what modifications are allowable.”

- Would the highway department allow public artwork and lighting on the underside of the Westway?

- Would property owners allow a storage facility for items needed for pop-up events to encourage further use of the site? tables and chairs? bins and bin bags? work benches for boaters and cyclists to do repairs?

- Would the bus facility allow lowering of the retaining wall and removal of barbed wire as elsewhere along the retaining wall? Opening up views and allowing light to penetrate?

- Would CRT create a bookable mooring(s) for roving traders to sell items and act as caretakers? Could a uniform ground treatment be installed, to reduce conflict between users and allow for greater flexibility of use?

Hopkins cited the Royal Parks for demonstrating how a uniform surface and appropriate signage can induce cyclists to give way to crowds and during events.

With those questions answered architects could produce a final design to heal a historic wound and with it, perhaps, create a new paradigm for local government, CRT and private entities to collaboratively wring utility for canalside locations across London.