old billy

the world's oldest horse

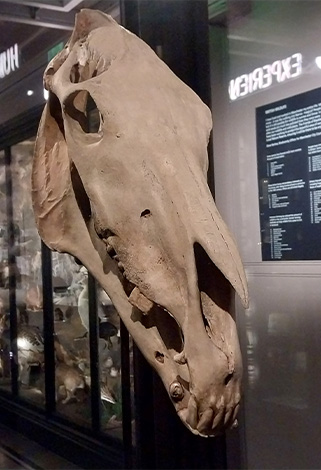

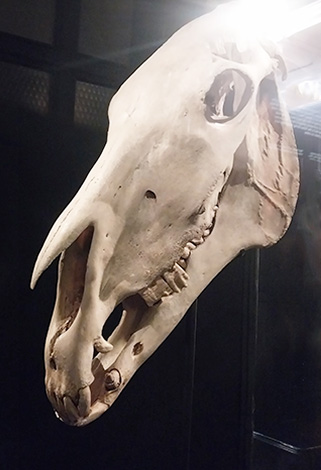

A recent foray into the wilds of the city took us into the Manchester Museum where, hidden slightly at the back of room full of other deceased creatures in various states of undress, is a horse skull. There is a neon sign high above the glass case that says “Old Billy” but with the exhibit being just a few feet from the wall, the lights are often missed and people walk by, not connecting the skull with the painting or the slightly monosyllabic information board on the opposite wall.

There’s nothing particularly remarkable about the skull unless you are a horsey person, in which case you may well notice the remaining teeth are more than a little geriatric. This is because the owner of those teeth was 62 years old when he died in 1822, an age that has never been matched even with today's advances in veterinary science.

What’s this got to do with waterways, I hear you ask. Well Billy belonged to the Mersey and Irwell Navigation Company.

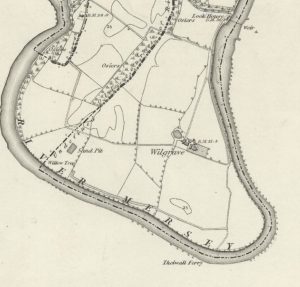

Our story begins in 1762, at Wilgrave Farm in Warrington. The farm sat in a loop of the River Mersey and the horses grazed in fields that overlooked the boats manfully trying to navigate up the river. The Mersey and Irwell Navigation at that time was undergoing a bit of a crisis, having been happily running something of a transport monopoly until Francis Egerton popped up with his brass-balls and started building the Bridgewater canal, spooking the company into finally addressing some of the serious navigational issues.

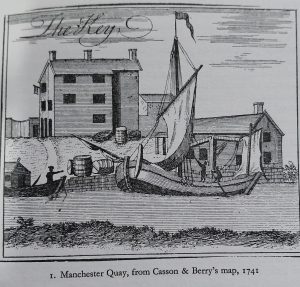

The navigation was populated by broad-beamed, flat bottomed barges that could carry about 35 tonnes if there was enough water, but in the summer especially, there was a distinct lack of water and their masters would be forced to reduce the cargo to about 15. Even then, boats could find themselves getting stuck on the shallows and having to be flushed off by dint of the closest lock being opened and everyone crossing their fingers.

These boats were broad, bluff vessels with a single mast and sail that allowed them to deal with the estuary, and when they couldn’t use their sail they were initially pulled by gangs of men. There was a shift in this, however, and when Billy was foaled in 1760 it was mentioned in the Act of Parliament for the Bridgewater canal that horses were a motive power.

There is some room for debate as to whether Billy was born at Wilgrave farm or whether he’d been bought as a youngster with the intention of breaking him in, but it is most probable that Billy was foaled at Wilgrave farm itself. He may well have been intended as a carriage horse; the contemporary accounts noted he had a look about him of the Arabian horse and as his ears were cropped - a revolting fashion for the time and an act you’d typically carry out on a horse before it was big enough to, quite rightly, kick your face in when you took a knife to his ears.

Billy was a powerful, stocky youngster standing at around 14.2 hands high. He was about 2 years old in 1762 when he was handed to teenage horseman Henry Harrison, who began the process of training him “for the plough.”

Perhaps because of the training methods of the time (or perhaps as a response to having his ears cropped, his tail docked and quite probably also getting his gonads done for good measure in an age with no anaesthetic) Billy grew up with a vicious streak and a tendency to bite and kick. This is not an ideal trait for a plough horse and quite possibly why he was quickly sold on, probably straight to the Mersey & Irwell Company.

Despite what a quick Google search might tell you, a contemporary account written in the horse’s old age tells us that Billy spent the next 30 years as a gin horse before going on to pull boats. This isn’t surprising - a gin horse would be hitched to a draw bar that rotated round a vertical axle, creating motive power for machines, and smaller, compact horses were preferable simply because they would fit to the gin better. The Mersey & Irwell company themselves would have had gins everywhere for anything from powering winches to pumps. There were gin powered corn mills and saw mills, and portable gins that could be loaded into a cart and dragged off to where it was needed, perhaps meaning that Billy might have been coming out with a team to help free off loaded boats caught on shallows.

According to the account, Billy began pulling boats quite late in his career. We can speculate that this could have been something to do with his temper, which didn’t mellow until he reached advanced old age, and pulling a boat would have kept the driver at a fairly safe distance from lashing feet, nor would anyone have looked twice at a boathorse being thrashed.

At some point, someone in the company realised exactly how long Billy had been on their books for and it dawned on them that they might actually have something a bit special on their hands. In 1819 Billy was pensioned off with none other than Henry Harrison once more assigned to his care, and he moved the Latchford stables of William Earle, one of the directors of the company, finally allowed to mooch about on his own terms.

In the summer warmth, Billy trotted and galloped stiffly with youngsters more than 60 years his junior and in the winter he stayed in his stable, rugged and fed soft linseed mash. His attitude, although mellowed by the years, did not improve all that much and legend says that he was supposed to come out for the coronation parade in Manchester in 1821, but refused point blank to leave the comfort of his stable.

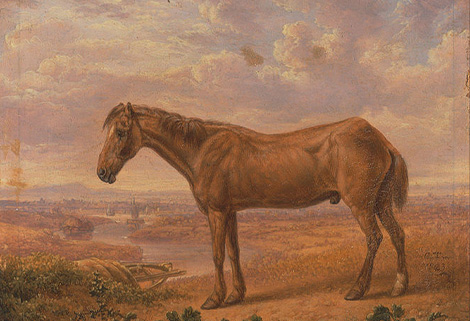

Perhaps realising that time was running out for the curmudgeonly old horse, William Earle commissioned the famous sporting artist Charles Towne to come out for him. Towne, in the company of a vet named Lucas and a man named Johnson who appears to have been a reporter of some kind, met the horse on the 11th July 1822 and everyone was suitably impressed by the old stalwart.

The painting shows a gaunt animal with a thoughtful face. The lack of ears makes him look worried, and although his hips jut through his skin, you can still see the powerful build that made him such a success in his career.

Billy died that winter, either on the 27th November or the 11th December, quite possibly finally succumbing to malnutrition as his worn teeth would have made it difficult for him to take much good from hay and it was long before the veteran feeds of today.

Not unexpectedly perhaps for the time, he was taxidermied, although for some reason it took 2 years before someone decided to do something with the remains and gave them to the new Manchester Society of Natural History in 1824.

Not unexpectedly perhaps for the time, he was taxidermied, although for some reason it took 2 years before someone decided to do something with the remains and gave them to the new Manchester Society of Natural History in 1824.

For some reason, Billy was displayed in the nude, with his skeleton out on display while his skin was “under the stairs” in a box.

Billy’s remains were moved into the newly built Manchester Museum around 1888, but exactly what of the remains made the move is questionable. Certainly his skull made it, and became an exhibit, but the rest of his skeleton appears to have gone missing, along with most of his skin. I say “most” because bizarrely the skin of his head was restuffed and ended up travelling 160 miles south to Bedford, where it apparently still remains today.

Despite his mortal remains having a slightly ignominious fate, he is still an important part of Warrington’s heritage life, with the local museum holding a special event on the 200th anniversary of his death and his story being immortalised in a charming illustrated children’s book last year.