science, technology and a curious mind

it's amazing what gets dredged up

Ever wondered what’s involved with dredging our waterways or the kinds of unusual objects that have been found? Well I went along to meet my former colleague Nick Smith National Waste Management Surveyor for the Canal & River Trust (Trust) to find out how the Trust operates.

Our canals and waterways are generally slow moving bodies of water, which means that as sediments enter into the canal, they will not be flushed out and will accumulate at the bottom. This leads to a reduction in navigable depth and dredging is conducted by the Trust to remove this unwanted sediment and keep the waterways navigable.

The Trust manage around 2000 miles of waterways[1] and it isn’t always easy to determine which stretches of canal need to be dredged and when. Nick explained that, “Some locations are more prone to problems than others; for instance, inputs from feeder streams (particularly during periods of heavy rainfall) can block a waterway, sediment movement in river navigations can result in sand bars blocking navigations and fly-tipping into the waterways is a regular problem that can prevent navigation”.

How does the Trust identify when dredging is needed?

The Trust are focussing on improving navigation, so use several metrics to determine when to programme dredging on a waterbody:

- Rolling 8 year programme of hydrographic surveys around the waterway network, which measure the depth of the accumulated sediment

- Investigation of complaints and comments from boat users help prioritise the dredging programme

- The popularity and commercial usage of a waterway

- Positive management of a waterway to remove historic contamination, improve flow and deliver environmental benefits, where funding (including match funding) allows

Once a stretch of waterway has been identified as needing further investigation, the Trust will then determine:

- Whether it is small scale i.e. around bridge/tunnel entrances and winding holes and can be returned to normal by conducting localised dredging called ‘spot dredging’

- Whether it requires larger scale dredging or main line dredging

- How much sediment needs to be removed

- The quality of the sediment

Dredging is an expensive operation and costs can increase if the sediment contains many contaminants. This means that every time a stretch is identified as needing dredging, then sediment samples must be obtained to determine its disposal route. The sampling strategies may vary, depending on the historical use of the area. Therefore extra samples may be taken in industrial areas or around historical discharge points.

How do you sample the bed of the canal?

Samples are typically taken by an Eckman bottom grab sampler or using a bucket. The Eckman sampler looks like a box with a sprung digger scoop on the end. On the shallower waterways, the bucket is typically attached to a pole and activated by pulling a lever. The digger teeth shut, enclosing the sediment inside. For deeper bodies of water, samples are obtained by boat using a grab sampler at the end of a rope. The grab is triggered by dropping a weight onto the spring mechanism.

Bucket sampling consists of a bucket attached to a pole or role. The bucket is then dragged over the sediment and accumulates within the bucket.

The sample is then brought to the tow path or side of the waterway and put into labelled sampling tubs and sent to a laboratory for analysis. A picture of the grab and sampler are shown in the picture below

What are the sediment results used for?

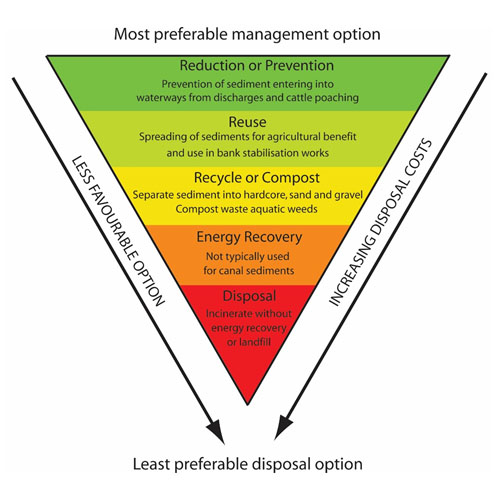

The results of the sediment samples are used to characterise the sediment in accordance with the Waste Management Regulations 3 2018[2]. These sediment results will help the Trust to determine the best reuse or disposal strategies for the sediments. The Trust applies the Government principles of the Waste Management Hierarchy[3]. The diagram below gives examples of how sediments arising from dredging can be managed.

Diagram of how the waste management hierarchy is applied at the Trust

The diagram shows that the preferred route is to prevent sediment from entering the canal. This isn’t an easy task, as many historical discharges are undocumented and may enter the waterway below the water level. Despite this, work is ongoing within the Trust to reduce sediment contributions to waterways from cattle poaching (the breaking down of banks where cattle drink from waterways) and ensuring that any new surface water connections have interceptors/sediment traps to prevent contaminants and sediments from entering waterways.

The diagram shows that the preferred route is to prevent sediment from entering the canal. This isn’t an easy task, as many historical discharges are undocumented and may enter the waterway below the water level. Despite this, work is ongoing within the Trust to reduce sediment contributions to waterways from cattle poaching (the breaking down of banks where cattle drink from waterways) and ensuring that any new surface water connections have interceptors/sediment traps to prevent contaminants and sediments from entering waterways.

Sediments can also accumulate in waterways and feeder reservoirs from excessive algae and plant growth. As algae and plants die off, they can form an organic mud layer on the bottom of the canal or reservoir. Excessive weed growth tends to arise when there are high nutrient levels (typically from available phosphorus and nitrogen) within the waterbody and sediments. Increased nutrient levels are often referred to as eutrophication. Even if nutrient levels are reduced, it can still take waterbodies over 20 years to recover from eutrophication[4]. Unless nutrients are removed, they will continually be recycled within a given waterbody. The picture below shows a blue green algal bloom at Olton Reservoir between 2006 and 2010.

Blue green algal bloom at Olton Reservoir

Some stretches of canal are prone to excessive weed growth from nutrients entering into the Trust’s waterbodies. In these areas, weed boats are used to collect the weed and keep the waterway as navigable as possible. The weed then needs to be disposed of, so providing the waste does not contain too much litter or plastic, it can be sent for composting at a dedicated facility.

Removal of excessive weed growth in the Birmingham Canal Network

There are numerous ways to reduce, reuse and recycle the volume of sediments created by dredging. Reduce, is predominantly using bank protection to prevent erosion, controls on inflows to reduce the amount of sediment, with the aim of reducing the amount of sediment ending up at landfills. Some sediments are suitable for reuse under a waste management exemption and may be used to repair banks.

Sediment reuse as infill to repair an eroded bank

In some areas, it is possible to separate fractions of the dredged sediment into large debris, gravel, sand and fine sediments. These can then be re-used and recycled by reusing the large pieces as hardcore, the sand and gravel can also be used for building materials. This will hopefully leave only litter and woody debris and the finer sediments in need of further recycling (where possible) and landfill, thus reducing the cost considerably.

It can be difficult to recover any energy from canal sediments, as they are typically have a low calorific value. Some hazardous sediments, containing high levels of oils, metals and chemicals may be sent for incineration, but typically high temperatures are needed to safely dispose of the contaminants[5]. The ash will probably require disposal in a landfill accepting hazardous waste.

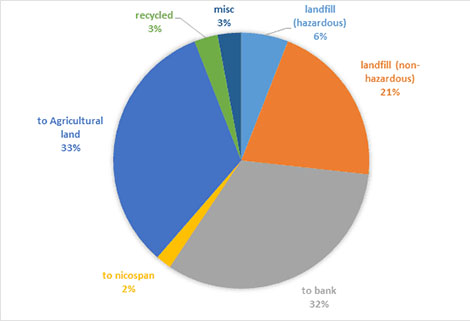

The diagram below shows how the Trust disposed of their sediments over the past year. The majority of sediment went to either waterway banks or was spread on agricultural land.

Canal & River Trust sediment disposal routes for 2017

Other considerations

As dredging programmes are conducted all year round, additional sediment samples may be taken to identify areas where water quality may be impacted. High water temperatures during the summer months may cause environmental complications to the dredging process by reducing oxygen levels more than expected. Some sediment samples will be analysed for nutrient content and potential impact on oxygen demand during the dredging activity. Where additional risks are identified, dredging may be re-scheduled to cooler months or additional work will be undertaken to herd fish away from the working area.

The final word

When I worked for the Trust, we came across all sorts of random objects that had been dumped in the canal, ranging from scooters, shopping trolleys, wood, dead animals, goldfish, general litter, car tyres and sometimes whole cars! Talking to Nick about some of the less common objects, he said ‘more unusual items tend to be safe’s, guns, terrapins and in one instance an alligator snapping turtle in Earlswood reservoir!’ The good news is that the alligator snapping turtle was re-homed to The West Midlands Safari Park.

The bottom line is, please do not dispose of anything in a canal. Large objects, unwanted pets, litter, waste liquids, plants all contribute to increasing costs and frequency of dredging. I will leave you all with these snippets of some of the objects found around our waterway network!

Alligator snapping turtle removed from Earlswood reservoir

Volunteers removing fridges, scooters, car parts, cans and much more from the Tipton canal ca. 2006

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Clifford Rowley for the waste hierarchy diagram and to Nick Smith for his help with the writing of this article. My thanks too to the Canal & River Trust for very kindly permitting the reproduction of their photographs in this article.

[1]More information about the Canal & River Trust can be found here

[2]More on the Waste Management Regulations 2018 can be found here

[3]More information can be found here

[4]McCrackin M.L. et al. (2017) Recovery of Lakes and Coastal Marine Ecosystems from Eutrophication: A Global Meta-analysis. Limnol.Oceanogr. 62, 507-518.

[5]Mulligan N. et al (2001) An Evaluation of Technologies for the Heavy Metal Remediation of Dredged Sediments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 85 pp145-163.