a thorny rose

To many of the uninitiated, the canals offer a bucolic, romantic way of life that could easily be part of “the darling buds of may”, but in truth there is a brutal edge to it and there are some topics in the canal world that are almost guaranteed to cause verbal (and occasionally physical) fisticuffs, and today reader we’re going to don our tin hat and enter the trenches of roses and castles.

The most often asked question is “Where did they come from?” A question in itself that is rather wrong, as the implication is that the style we see today has been the same since the Duke of Bridgewater said “Hey I think I’ve got a great idea”.

There is a lot of popularity behind the idea, largely thanks to Rolt’s writing, that the Romany folk came to the water very early on and brought their art with them, but there is scant evidence of them joining the canals at all and in practice the painting theory doesn’t work simply by dint of the fact that there is artistic evidence of rose and castle type paintwork on boats that predates the development of the painted ‘vardo’ that everyone thinks of.

The earliest imagery we have dates to 1820, and a painting by an unknown artist. It is only just visible, but it appears the picture panel on the cabin side bears flowers. The next one is 1838 and also has a floral picture panel.

The first written description of artwork that can be confidently identified as roses and castles appears in 1858 and gives us the biggest lead:

“The boatman lavishes all his taste; his rude, uncultivated love for the fine arts, upon the external and internal ornaments of his floating home. His chosen colours are red, yellow and blue... the two sides of the cabin...present a couple of landscapes, in which there is a lake, a castle, a sailing boat, and a range of mountains, painted after the style of the great teaboard style of art... the brilliancy of a new two gallon watercan, shipped from a bank-side painters yard.. displayed no fewer than 6 dazzling and fanciful composition landscapes, several gaudy wreaths of flowers, and the name of its proud proprietor...running round the centre upon a background of blinding yellow.”

The crucial information here is the description of it being painted in the manner of a teaboard.

An object that households rich and poor alike had: a teaboard is just a tray intended for carrying the teapot and its accessories, and for the best part of 100 years tea trays were predominantly jappaned.

Developing just prior to the canals, jappaning is western imitation of Asian lacquer-work that started out on eye-wateringly expensive furniture and moved onto smaller household items as it became a craft suitable for young ladies of quality to indulge in. These young ladies also indulged in gilding (putting gold and silver leaf on things) and filigree (twisting wire into intricate shapes), and decoupage (sticking paper decorations to things and lacquering them into submission.)

As with all forms of fashion what the rich had, the poor wanted a piece of; by the time the canals were firmly established in the 1820s there were around 40 companies in the West Midlands mass producing japanned objects on tinplate and papier-mâché, a figure that kept rising right up until the mid 1870’s (when enamelling became trendy instead). The imagery that was most popular with jappaning was poetic landscapes and botanicals, with roses being particularly popular.

Mary Delany is arguably a woman to blame for the craze of flower decoupage, creating a series of remarkably detailed “paper mosaiks” of flowers from tissue paper from 1772 to 1783.

Imitators down the years, especially when mass production became key, were not as skilled. The same imagery was rammed down the consumer's throat on every surface; the advent of ‘transferware’ china allowed patterns to be printed ad infinitum and brought the boom in the ‘Willow patterns’ on pottery that the boats themselves were key in spreading round the country.

The boats themselves would have had it in their cupboards, it was everywhere. Tea could well be brought out in a blue and white tea-set covered in castle scenes and served on a tray like a florists catalogue.

People often overlook the fact that it wasn’t until quite late in the Victorian era that the boaters slipped down the financial ladder, and also that women were on the boats with their menfolk quite early on - in 1819 John Hassell noted there were “generally one or two females generally attending each boat” and in 1824 the Chester Courant noted that the boatman’s “wife is on board” as general knowledge.

Boatmen could be on a continuous cycle of trips for weeks, if not months, on end, so it wouldn’t be unreasonable for the couple to want to stay together where practicable, and the economic aspect wouldn’t be unwelcome - better to pay your own crew than a stranger after all – so it’s quite probable that art came to the water via the rather boring medium of fashion trickling down the social ladder and first coming into the cabins attached to the household goods of the boatman’s family.

How did we make the leap from fancy lacquer tea tray to painted table cupboards? The real answer is we may never know. Everything was painted and there were painters everywhere, and indeed the same man might be employed painting trinket boxes in the morning and slapping the owners name on the cabin side at dinner.

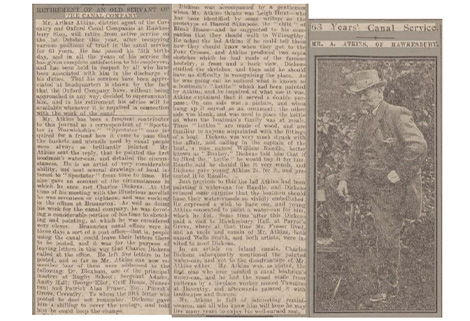

There is the odd legend of Arthur Atkins, a toll clerk for the Oxford Canal Co who claimed in the Coventry Standard in 1914, the occasion being his retirement, that he had painted the first boater's watercan and that in around 1858 he’d been at Braunston and sold Charles Dickens a boatman’s kettle (a fancy wooden trivet, plain on one side, painted on the other), the great author promptly gifting said piece to the Captain of a boat and wrote an article about it all to the great advantage of Atkins.

The story has more holes then a June bride. For a start we can see that painted cans easily predate 1858 and there is simply no record of anything like that happening with Dickens at all. There’s no trace of this article he supposedly wrote and in general his canal contact was fairly limited. It’s also highly convenient that date of the incident matches with the journey I quoted originally, the journey that was published in Charles Dickens’ magazine ‘Household Words’.

It is almost certain that young Arthur Atkins was present when the author of that journey, John Hollingshead, passed through, so it is plausible that it could have been a case of mistaken identity, but our source says the can was “newly shipped from a bankside painter” long before the boat they were travelling on arrived at Braunston.

Intriguingly however, a search through the census shows that Atkins father, also called Arthur, was a painter. At Akins' birth at Bedworth in July 1840 his father is recorded as a baker, but 6 months later in the census he’s a painter. In 1851 he shows up at Braunston as a canal clerk, but this doesn’t suit all that well because in 1861 he’s gone to Birmingham and he’s a painter again. 1871 records him as a “Writer and painter”, which suggests signwriter, 1881 “decorative painter” and 1891 hes still wielding a brush in Birmingham as a “Painter and decorator”.

Given the fluid job descriptions, there’s a distinct possibility that the Arthur Atkins, boatbuilder’s foreman, declared bankrupt in 1869 is this same mysterious painter. Could it be his paintwork his son claimed as his own?

The Coventry Standard notes how Atkins jr was a “regular correspondent” with their writer Spectator, and although many of these have weathered the years quite badly, those that are legible give off a distinct air of someone over egging the pudding. It’s quite plausible that Atkins embellished or completely made up his stories, knowing that there was no way for anyone to verify the details.

The crucial thing to bear in mind when delving into the paintwork is that the vast majority of surviving examples post-date the first world war. The war decimated the male population and left the country with a dire shortage ofyoung men from all the trades, from farriers to painters. A pet research project of mine so far suggests that 65% or more of boatyard painters were lost, and that’s not including the individuals, boatmen or otherwise, who could be classed as ‘hobby painters’.

A cursory glance through museum pieces shows the abrupt change from diverse bouquets and landscapes to the ubiquitous roses and castles, which is most likely a direct result of there being far fewer painters and therefore far fewer styles, attending the same number of clients who now had a far smaller budget as the canals being the slow descent into financial loss.

By the 1930s, the aesthetic preference of the public had changed from the sleek art nouveau to the geometric art deco and more professional painters slipped away. The Grand Union Canal Carrying Co leapt onto the scene in 1930s and demonstrated that by their modern paint scheme – simple two tone blue, plain lettering and even replacing the elegant “mouse ears” on the back cabin with dull rectangles. Grand Unions attitude to paint may even have been a contributing factor in that they could never get enough crew to work their massive fleet, as the boatmen themselveswere not fans of the change and more than ever started to take up their brushes to embellish their boats themselves.

This brings us almost to the modern age. When the trade failed and the pleasure boats started to appear, objects covered in canal painting became trendy souvenirs and both boatmen and painters alike readily filled the market. New painters began to emerge, grabbing on to every opportunity to learn from those masters from “the old days” and patiently working their way along the long slow path to becoming masters in their own right.

Today, the canals are once again flush with painters at every corner and, much like it was in the beginning, there are masters and glorified finger painters, and every level of skill in-between.

Beauty is of course in the eye of the beholder, and at the end of the day I can only repeat the wisdom of the infamous Ron Hough himself: “The only person that has to like your painting is the person who’s buying it!”