tales from the old cut 4

the miners of crick

The little village of Crick is these days best known for the annual Crick Boat Show, thousands of pounds worth of canal related paraphernalia is showcased in an attempt to get visitors to mortgage a kidney and buy some of it. The show is, these days, all about the modern boat, and while the visitors may comment on how picturesque the location is, rarely does the history of it cross their minds.

A casual walk down the towpath from the show-ground will lead you to the mighty tunnel portal, where if you stand on the water’s edge and face the tunnel, you will find a small, worn brick inscribed with a date.

A casual walk down the towpath from the show-ground will lead you to the mighty tunnel portal, where if you stand on the water’s edge and face the tunnel, you will find a small, worn brick inscribed with a date.

On that date, with great pomp and circumstance, a boat loaded with the great and good was legged through, the tunnel declared officially open and everyone clapped themselves on the back for completing such a momentous task.

Of course, the people in the boat that day hadn't lifted more than a pen in actually getting the tunnel built, and most history books that a visitor to the boat show can pick up, only speak of those fancy suited gentlemen.

I, however, prefer the grubbier story of the tunnel, the one full of blood, sweat, tears and a lot of sex.

We'll bypass the boring paper-trail and begin our story in 1810. The village was a busy little place, sat comfortably on a trade route between Oxford and Leicester, and the travellers it tempted supported a selection of forges and inns. The village was still hanging onto its cottage crafts in the weavers, spinners, shoemakers and saddlers, and it was forward thinking enough to have a couple of day schools, an apothecary and a doctor. It of course had the usual butchers and bakers, and obviously a good selection of farmers and a lot of labourers.

There were masons at the stone pits and at least 2 brickyards quietly churning out building materials, and in 1810 it is our brickyards that open up our story by signing up to produce 2 million bricks for the princely sum of 1 & ½ farthings per brick, or 32 shillings per thousand.

Within a year, the busy little village was bustling more than usual. There doesn't appear to be a full list of who was employed, so it is impossible to say how many men were professional canal builders and how many were local labourers ready for a change of career, but we know that 350 men were employed and were making rapid progress.

There was a minor blip late in 1811 when the labourers had nearly finished a deep cutting at one end of the new tunnel, when someone with a theodolite and some sense, dug test bores for said tunnel and found it dangerously unsuitable.

A few frantic meetings later, and a new site was chosen on the other side of the village and work restarted with all haste.

Haste is perhaps the operative word here. The new site had less shifting sand, but it did have streams. By late 1813, the tunnel itself was well past the halfway mark, but at least one man had died at shaft 10 (stories differ as to whether he fell down it or whether something fell down it and landed on him), and a few others suffered “some maiming” from roof falls. This was on top of the usual range of accidents, with at least one man being run over by a full wheelbarrow that slipped back on him; humorous this might sound at first, remember that these were timber monstrosities shod with iron and loaded as heavily as possible.

You may have noticed that so far, I have carefully avoided using that dreadful term: “navvies.” We must remember that there had been no real concept of tunnel building prior to the canals arriving. If you were digging tunnels you were generally a miner, and it is this logic that accounts for our first glimpse of the real men behind the tunnel each being recorded in the parish register as “miner.”

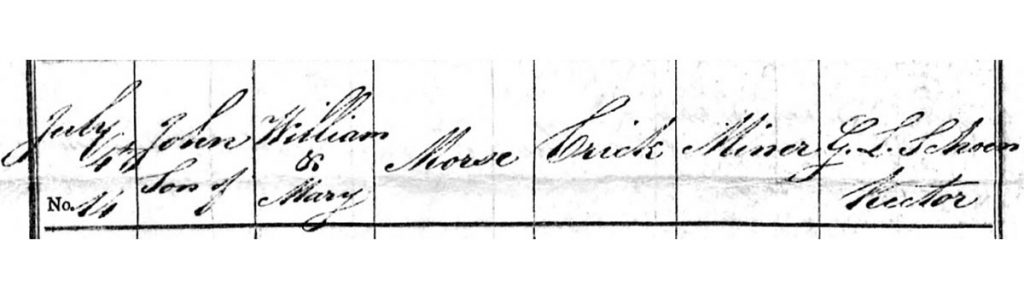

Meet William Morse, his wife Mary, and their baby son, John.

We don't know where our miners lived; if we take the sister site at Husbands Bosworth as a guide, we can assume that somewhere near to the site would have been a couple of long wooden dormitory huts capable of housing a couple of hundred men. They were being quite well paid (contrary to the mental image one might get when one thinks of the canal builders), so it is likely that some of the men, perhaps the married ones, would have rented rooms in the village.

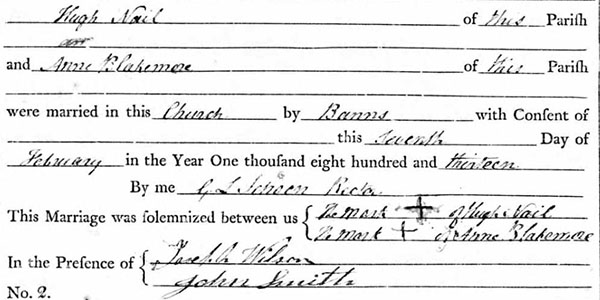

They certainly would have descended on the village after the day was done in search of sustenance, and it is likely that it was during one of these sorties into the village that Hugh Nail first spotted Ann Blakemore.

Hugh seems to have been born on the outskirts of Liverpool and joined the canal gangs aged around 14, then made his way around the country, digging as he went. We can speculate that he arrives on the scene fairly early in the proceedings, as by the time he goes to the Rector in January of 1813 asking for the banns to be called, he's considered “of the parish.”

Hugh and Ann leave the church hand in hand watched by Ann's family and, chief among Hugh's fellow miners, his best friend Joseph Wilson.

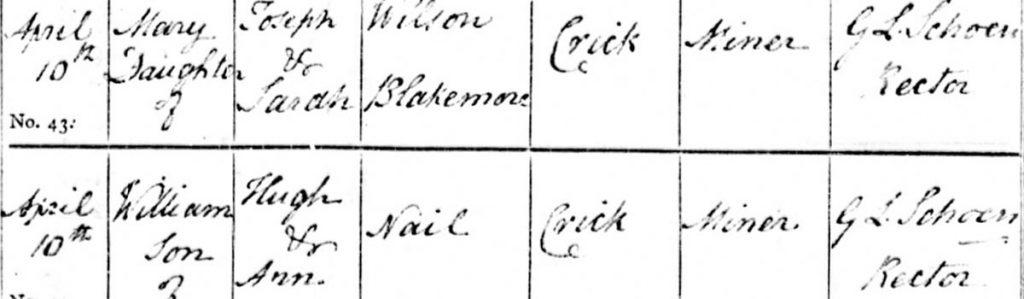

Perhaps it was this romance that introduced Joseph to Ann's sister Sarah. Indeed, perhaps it's in an advanced state of alcoholic refreshment following the wedding that Joseph and Sarah became more intimately acquainted.

The following year, Hugh, Ann, Joseph and Sarah make their way back to the church where the resigned Rector baptised William and Mary respectively.

It may surprise you to learn that Sarah and Joseph stay together and produce a son the following year.

Sex before marriage didn't carry quite the same badge of shame for people of the regency era, especially the “country folk” who were frankly far more understanding of the mechanics and didn't bat an eyelid at a woman walking up the aisle with a big belly. Illegitimate children were frowned upon but once they'd arrived no one really bothered about them provided they were cared for without posing an expense on the parish.

In fact, Crick appears more tolerant than most as the Rector doesn't bat an eyelid when George Crowder and James Schofield leave the tunnel for a walk out with Esther and Sarah Vaus and produce babies John and James, or when William Harrison downs his shovel to dally with Hannah Gent and produces another baby John.

Indeed, the only time we see anything that could be taken as disapproval is when the Rector notes in 1811: Nov 12th. I privately baptised Mary, daughter of James and Ann Morris. The father (a brickmaker) having absconded and the mother with the infant being about to undertake a long journey.

Perhaps James had been overwhelmed by the amount of bricks the new tunnel had demanded.

We can't avoid the potential that some sex work was taking place at this time, but there is no evidence to suggest that the babies were the receipt from a miner’s night-out.

Considering how many men were working on the tunnel and the reputation that they gain later in the Victorian period, it is refreshing to see that out of 16 children baptised, only 4 are born fully out of wedlock, and a fifth whose parents had the banns called, but they don't appear to actually manage to get up the aisle. Percentage wise, the miners are veritable gentlemen against the rest of the village.

There are many more stories of these forgotten men waiting to be uncovered, and I hope to find the rest of their names for a start.

It seems likely that it's thanks to these men that Crick gained the story that it had a treacle mine, but I like the fact better - that these men mined for a canal and found it.

Tunnel Miner Rollcall:

William Morse, Mark Flint, George Crowder, Edward Corby, James Cope, William Cox, Richard Hodges, John Betty, Joseph Wilson, Hugh Nail, William Harrison, John Jones, James Schofield, George Hillyard