tales of the old cut

death on the water

“ ’Tis impossible to be sure of any thing but Death and Taxes.”

The Cobbler of Preston, by Christopher Bullock

The death of Queen Elizabeth II has just allowed the world to witness the pageantry of a monarch’s funeral in all its traditional splendour, and naturally it got me thinking.

Despite its inevitability, the civilised world of today finds death traumatising and disturbing and uses the technology of modern life to keep its mortality out of thought and mind. This is, really, a completely new phenomenon that our ancestors would not have understood in the slightest.

At the time when the canals began, the majority of people didn’t move much beyond the district they were born in and if they did, they could be hoiked back to their village of origin by the settlement act if they had the audacity to be so poor as to need parish relief. The vast majority of people were also unquestioningly religious in one form or another, with a fairly iron-clad belief of life after death.

Death itself generally took place at home in the company of family, who had usually also been acting as the medical team prior to the event and the cause was usually an illness that gave them and their family time to acclimatise to the approaching decease. Sudden, accidental deaths were not commonplace and, then as now, caused more distress to the people around them; the parish registers would often be annotated by a shocked curate with the event.

To this background, the roving bands of navigators arrived on the scene.

They were tough men. Skilled and well paid, they arrived at quiet villages and caused chaos simply by doing their job. When death came to that community, it was usually brutal and it hit the men hard. At Standedge, a delayed blast instantly killed a man and wounded 3 others; near Sheffield a man was buried alive when a cutting collapsed; at Crick a man was killed falling down a tunnel shaft when a rope snapped.

The cortege that accompanied a man to his grave would surprise the locals, who viewed these strangers with accents from far off counties and with odd names like “Clainhim” with suspicion and the expectation that they were little more than unpredictable animals.

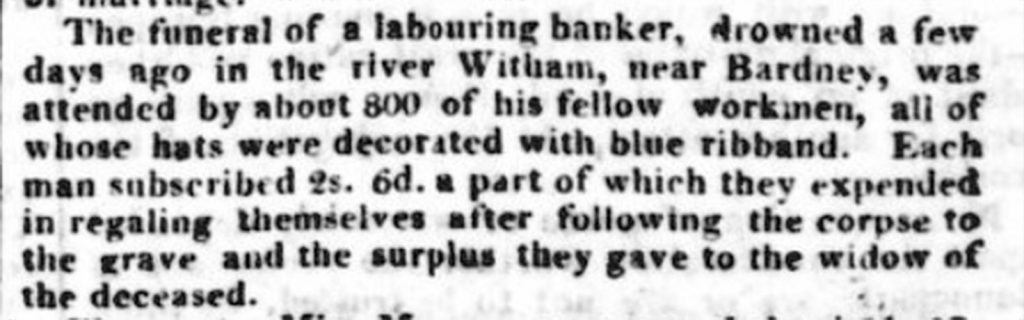

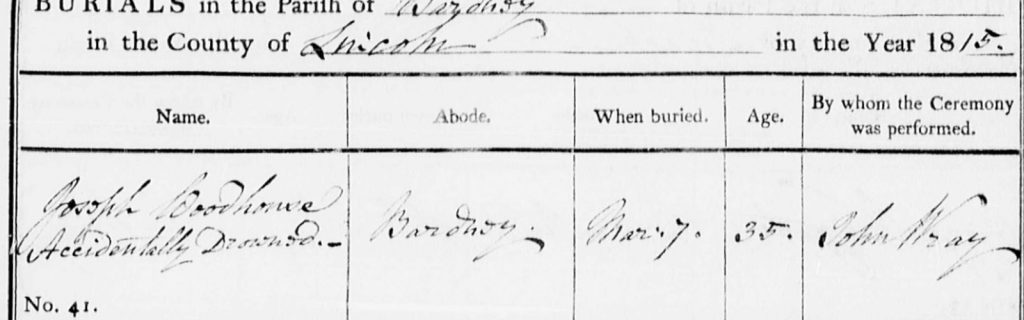

800 men fixed a blue ribbon to their hats and followed 35 year old Joseph Woodhouse in 1815. The latter group each put a half crown into a pot for the wake and then gave his widow the rest, the financial equivalent of about a year’s wages.

Joseph Woodhouse - newspaper clipping

Joseph Woodhouse - registered burial

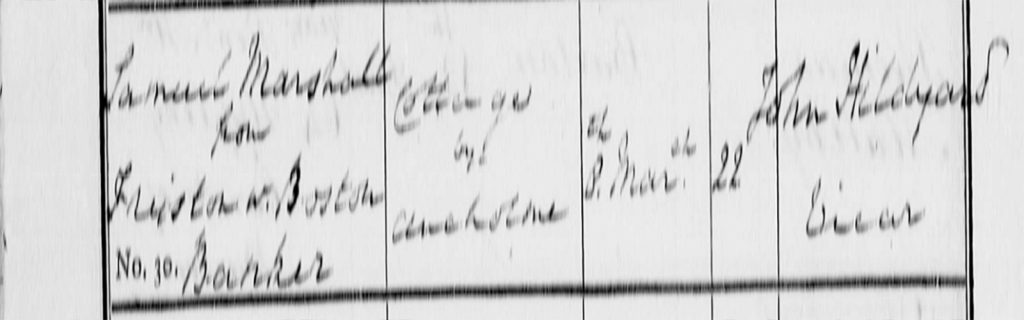

300 men with a white ribbon around their arm walked in silence behind the coffin of 22 year old Samuel Marshall on the 8th of March 1826.

Samuel Marshall burial

For a time, fear of death itself really came secondary to a fear of being body-snatched. Until the Anatomy Act was passed in 1832, there was good money to be made in half-hitching a fresh burial and selling it to the medical schools, and there was a distinct increase in the risk the lower down the social scale you went.

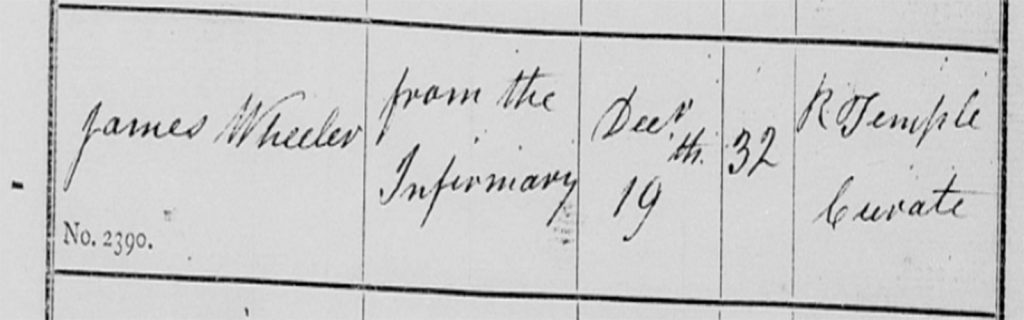

On the 15th December, 1830, 32 year old James Wheeler was fetching a barrow-load of stone from Cowley quarry when he slipped and fell to the bottom. His horrified workmates rushed him to the local infirmary, where he finally died two days later. The newspaper describes how the men now raised the princely sum of £5 for a decent funeral by dint of 100 of them putting a shilling in the pot.

A large gang of them went to collect James on the day of the funeral and were aghast at finding the coffin already nailed shut; not trusting the doctors not to have ‘interfered’ with the body – this being before the 1832 Anatomy Act - they demanded the lid came off so they could check and, faced with a large gang of powerful, irate men, the hospital eventually complied (the navigators fears were unfounded and James’ remains were perfectly fine.)

Death of James Wheeler

The funeral procession is what now gained the attention of the local newspapers. 6 men bore the coffin, while 6 women attended to the pall. Six foremen were the chief mourners behind the coffin and then 100 men walked behind, 2 abreast. More navigators and their wives were already at the church.

No one wore mourning clothes but everyone was scrubbed clean and smartly dressed.

When it came to the actual interment, they weren’t taking any chances that someone might body-snatch James and they insisted on filling in the grave themselves, allegedly having brought stones from the quarry itself to make sure he stayed buried.

The funeral practice of the first boaters was, at times, just a vaguely reverential rubbish disposal; in 1791 a boatman drowned legging through Preston Brook tunnel. His body was dropped off at the wharf and it appears the boat carried on her journey having quickly hired a replacement man. No one had any idea who the dead man was and it was the height of summer, forcing the Daresbury vicar to bury him quickly in an unmarked grave and to simply note in the registers “Boatman drowned in the tunnel of Preston [Brook], interred 26th day [of July]”

When death came to a boater, he was usually in his cabin. If the boat wasn’t already laid up, she would carry on her journey to the nearest place that could supply a coffin. The family would usually be the ones to attend the body, but in some places had a “woman that does” who would take this role.

Boaters, just like the navigators, wanted a “decent funeral.” The coffin would be as ornate as could be afforded, and often there would be a quick whip-around of the boats in the vicinity to make sure there was money. Some boaters were part of burial clubs, and in a few cases the company they worked for would foot a funeral bill.

Funeral fly-boating 1904

While they would strive to get the body back to the place the deceased most associated as home - Braunston being a famous example - generally, a boater would be taken to the closest canal-side church and interred with little circumstance. The funeral party really depended on where the boat had managed to get to; a quiet village might only have one or two other boats tied up there, while a busy wharf could have dozens. If the person had died by accident, the funeral could be delayed by the attention of the coroner’s inquest which would also affect what other mourners might be able to be present.

When a boat was able to take her dead home, this would entail loading the coffin onto the boat, usually behind the mast, and running ‘on the fly’ with it. This was a practical consideration of multiple fronts- not only was a boat not earning if she was on a ‘dead run’; embalming was not as long-acting as it is today, if it was even done at all. A boat with such a cargo would often be loosed through by other boats at locks, and the infamous ‘towpath telegraph’ would have been at work keeping other boats abreast of who’d died and where they were. This kind of funeral invariably had more mourners at the burial, having given them time to get their own boats to the place.

Boaters' funerals tended to attract little attention from the newspapers due to the sheer speed in which they happened, but in 1923 the boatmen went on strike and around 55 boats came to a halt at Braunston for 3 months, and it gives us a glimpse into their lives.

Three deaths attended the boaters: 62 year old Joseph Green off the boat “Flint,” 12 year old Edward Walker of an unidentified boat and Albert Kendall, a 67 year old retired boatman.

Joseph Green Burial (photo from Steamers Historical)

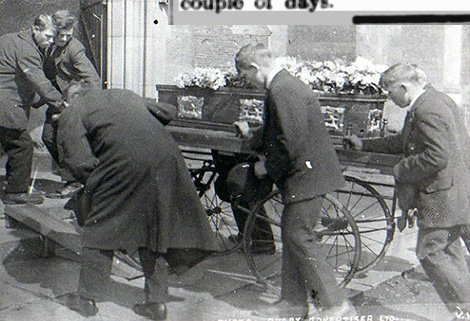

The funeral procession of Joseph Green was photographed showing the impressive cortege, and young Edward’s coffin was photographed being wheeled into the church by his young bearers. A newspaper describes for him “An extremely impressive site was presented as the cortege, numbering probably 100, proceeded from the Castle Inn, where the body had been resting, to the church… Many of the followers carried touching bouquets of wild flowers to place on the coffin.”

12 year old Edward Walker's burial (photo from Steamers Historical)

Albert, who appears to have been living in a cottage in the village, was noted as getting an equally impressive send-off “..there was a cortege of 135 of the boatmen and women who are at present held up at Braunston...”

When you look at the waterways funerals of the past and compare them to the Queen's funeral just days ago, there’s very little fundamental difference in what’s actually happening. A monarch being flanked by her loyal forces or a navigator being escorted by his comrades, it’s still simply a goodbye.