My previous post told the story of how our life aboard Art Deco ended and I thought that maybe it is a good idea to tell the story of how it started. How two relatively sane people of pensionable age decide to give up bricks and mortar, sell everything they possessed and invest in what is essentially tin can floating on water.

It all started with a chance meeting back in the spring of 2011. At that time my wife, Joyce and myself were the owners of a small cafe that we had started after being made redundant. Over time the cafe became a meeting place for the local community, mainly because we served excellent food and coffee courtesy of Joyce, but also because of the five computer terminals we had installed, offering customers free access to the internet. This had been my idea, to offer something unique in the hope of generating custom, which indeed it did. I was on hand to help folks who weren’t that computer literate to navigate the internet and generally offer encouragement and advice.

One Wednesday morning in May of that year a lady came in, ordered a coffee and asked if I could help her with the computer, she wanted to find out if there were any moorings available for canal boats in London. As we searched the internet we chatted and she told me that she was having a boat built in Tyler Wilson's yard on the canal in Sheffield and planned to take it down to London and live on it. I did not know it at the time but that one chance meeting would be the start of an amazing adventure.

The lady, Rosemary was her name, became a regular customer of the cafe and one day she invited us onto her boat for drinks. We were living in an apartment in the Old Grain Warehouse right by the Sheffield Canal Basin so we knew exactly where the boat builder was, in fact we frequently spent time chatting to the boaters who moored there. The cafe was closed on Sundays so the following weekend we made the first of many visits to her boat, which was in the final stage of the internal fit out with just a few ‘snags’ to sort out before she went on her way to a mooring in central London that we had found on the internet. Her son and family lived in the Camden area and she wanted to be close to them but couldn’t afford property prices and living on a boat seemed to tick all the boxes for her.

It was a lovely summer that year and we spent many a happy Sunday afternoon on Rosemary’s boat enjoying a glass of wine and each others company. On one occasion we were chatting away when the conversation led to what our careers had been before retirement. Rosemary and her late husband had been in the hospitality trade all their working lives, managing pubs and later small hotels. As we chatted she stopped, looked around her boat and said, “you know, a boat like this would be perfect as a floating hotel”.

I heard the words and immediately a light flashed on in my mind, I had an idea! We had been successful running the cafe, really busy with lots of trade, but it was proving very hard work. We loved the interaction with the customers but we were only just about earning the minimum wage even though we were working very long hours and it was beginning to tell, we were both in our early sixties for heavens sake! For some time we had been thinking of what our next move would be, where would we go, what would we do next. Our two children had left home, Adrianne was registrar at the Baltic Gallery of Contemporary Art in Newcastle and David was in Sheffield working as a digital graphic designer, so with no responsibilities we felt that we could do whatever we wanted and go wherever we pleased. I had been self-employed in the eighties, running my own graphic design studio, so I was familiar with going it alone and not afraid to take a chance. Rosemary’s suggestion of the floating hotel had fixed itself in my mind and I couldn’t let it go, it was an itch that I had to scratch!

I had no experience of the boating world, a couple of holidays on the Norfolk Broads was the limit of my boating knowledge, so a steep learning curve was going to be necessary if I wanted to scratch the itch and follow my dream. Joyce had agreed that in principal the concept was sound, her reservations were around the logistics and practicalities of catering for guests in the small space that a canal boat offered. We needed to know more about what we would be getting in to and the internet has made it extremely easy do. Research used to involve a trip to the local library, searching through books and magazines, finding and talking to people with relevant experience. Now courtesy of Google it can all be achieved from the comfort of your own living room.

The amount of information relevant to our needs was staggering, everything from individual blogs by boaters to detailed articles written by experts, and of course companies advertising their latest products. We spent many hours on our research and slowly a plan came together. It soon became clear that the ‘off the shelf’ option of a boat from one of the commercial builders would not meet our requirements, we needed a bespoke design to suit our project. As I mentioned earlier, I had been a graphic designer and although retired, I still had my Mac computer and design software and enjoyed creating illustrations, purely for pleasure. It was no big leap to transfer these skills to designing the internal layout and overall design of a canal boat.

The first decision to be made was the size of the craft. It would be our home we decided on a wide beam craft, 12 foot wide, as opposed to the standard narrowboat size of 6 foot 10 inches wide. (canal boat builders still use imperial measurements) This decision would limit our cruising range and we would have to decide whether to base ourselves on the northern or southern waters, Birmingham being the ‘pinch point’. The canals around this area were the first to be developed and the locks on them were built to accommodate the narrow boats, but as the network widened and trade grew, larger locks were constructed, enabling larger boats with more freight carrying capability to be built. Most of the older locks were never widened to accommodate wide beam craft resulting in the fact that Birmingham still remains a ‘pinch point’ in the canal system to this day. We decided to go south, mainly because the climate would be warmer, but it also gave us the option to cruise the river Thames as well as the canals.

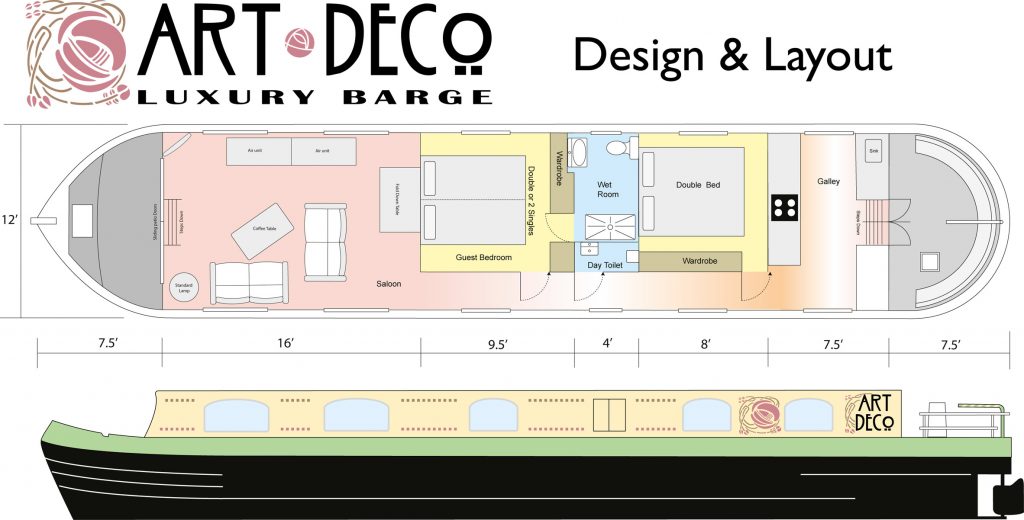

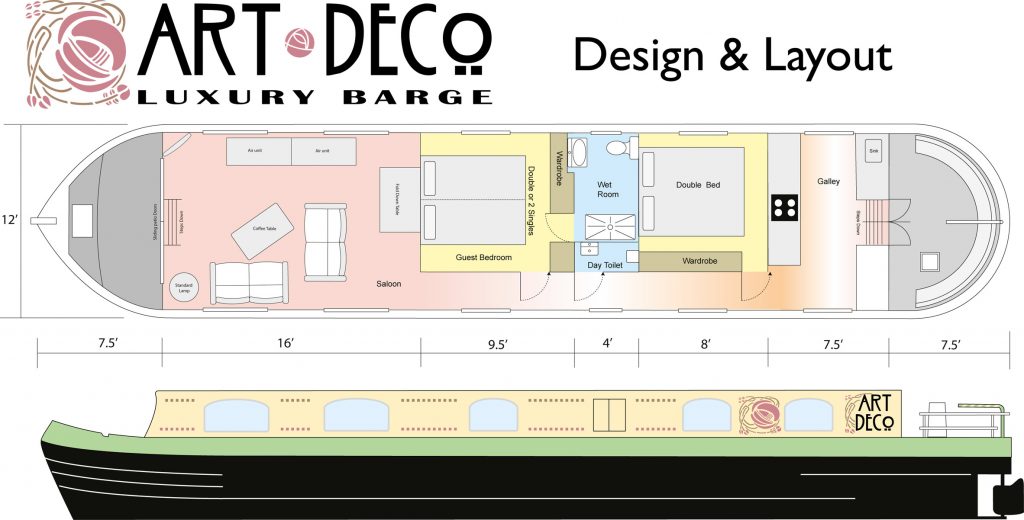

With those decisions made, I started working on the internal layout. Our plan was to offer a few days cruising experience to just two adults at any one time, so we would need a craft that could accommodate: two double cabins, one for ourselves and one for guests, along with a galley, saloon and bathrooms. Most wide beam craft have the main bedroom cabin in the bow and an open plan saloon and galley at the stern, with bathroom and bedroom cabins in between. Having no previous knowledge of internal boat layouts, I could not understand the logic of this layout, and still don’t. My layout would turn this design on its head, literally, I would put the saloon in the bow, with the galley at the stern and the cabins and bathrooms in between. My logic being that our guests would be able to sit in the comfort of the saloon, watching the world cruise by through the patio doors, while the cooking and it’s associated odours would be confined to the rear of the boat.

Another reason for putting the galley at the rear is that Joyce would be spending much of the day there, as we planned to offer guests all their meals: breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I would be on the rear deck skippering the boat, so we would easily be able to communicate with each other, essential, as I would need her on deck to help through the locks and bridges.

We decided to install a walk-in wet room and toilet in the guest cabin, with a separate small toilet cabin for our use when we had guests aboard. Given that our plan was not to have guests aboard full time, and only for a maximum of five days, and more importantly to save space, we thought we could get away with one shower, we would have plenty of opportunity to make use of the guest cabins facilities.

With the internal design finalised, we were in a position to determine the length and this was always going to be a compromise. It had to be long enough to accommodate all the rooms, but short enough to be easily handled. After much ‘tweaking’ we finally had a layout we were happy with resulting in a craft that was 12 foot wide and 60 foot long.

I could now turn my attention to the technical requirements and I had done quite a bit of research on canal boat engines. Joyce had insisted that if she was to provide three meals a day for guests she needed a well equipped galley, not the usual two ring gas hob with small oven that most boats have. I had read about a company who had adapted a Beta 75 marine engine to run as a hybrid system, providing both diesel and electric motive power. More importantly to me, they stated that their system could provide masses of 240 volt AC power, more than enough, they said, to power the galley that Joyce wanted. I contacted them and we entered into discussion regarding our requirements and after much debate we had exactly what Joyce required in her galley: 4 ring induction hob, oven, warming drawer, fridge freezer, microwave, dishwasher, cooker hood and washing machine. All full size A* power rated domestic appliances. The hybrid adaption powered all these appliances, along with 240 volt plug sockets throughout the boat.

The way it worked was simple; a 48 volt alternator was fitted to the standard Beta 75 marine engine, belt driven from the flywheel. This charged a bank of 24 x 2 volt motive power batteries, connected to a Victron Energy Charger/Inverter, Multiplus 48v, 5000 VA, 70 Amp. There was also a 48 volt electric motor in the drive chain which gave motive power when engaged. The only flaw with the system was that the batteries were only charged when the diesel engine was running or when the boat was connected to shore power. This should not be a problem for us as we intended to be ‘continuous cruisers’, out on the canals/rivers 24/7.

We had the design complete and from my drawings Art Deco looked a great craft, all that was needed now was for someone to turn the drawings into reality! During the summer of 2012 we compiled a list of boat builders who looked, on paper that is, likely candidates. We visited all of them over a period of few weeks working our way through the list before deciding on a builder who was based near Manchester, we placed the order and set the wheels in motion. The reason for our choice was that this builder seemed to be flexible and willing to follow my drawings and more importantly he was willing to allow me to paint the graphics. I wanted to have some physical input into the build and the graphics were my way of doing that. I also had a second, more devious reason though, it would allow me to be at the builders every day, able to ensure that I had the boat that I wanted, not the one the builder wanted.

By the autumn of 2012 we had said good by to our previous life, sold our apartment, (furniture included), car and motorbike and taken a 6 month lease on a flat in south Manchester, near to the boat builder.

The shell of the boat had been built by a yard in Stafford and was delivered to Manchester in November, ready for the fit out. The builders started immediately but I had to wait a few weeks while the shell of the boat was prepared, primed and painted with the base colour, a process that was not helped by the cream colour we had chosen for the upper part of the boat. Eight coats had to be applied before the finish was acceptable. By the time I started on the graphics it was mid-winter and the temperature was freezing, colder in the builder's shed than outside! In fact on occasions it was too cold for the paint to flow properly. It was slow and hard going, but at least I had an excuse to be at the yard every day, ready to answer the many queries and questions that inevitably cropped up. Had I not been on hand the build time would have slipped back and more importantly I would have had a boat the builder wanted, not the one I wanted.

The gods at last seemed to be smiling on us for once and the build progressed, a little slowly I have to say and over time I came to realise that our builder was defiantly ‘old school’, working at a pace that would have been acceptable in the 19th century. He didn’t understand the concept of a deadline, and we certainly had one. Our good luck didn’t last long though, the engineer from the hybrid company contacted me to say he had broken his ankle, was out of action for at least 3 weeks and would not be able to commission the engine. This was bad news indeed; the fit out of the boat was complete, the engine was in place and we were ready to go. After many heated telephone conversations it was agreed that he would come to the marina at Roydon and commission her there. The problem with that scenario was that we had to get ourselves and Art Deco there. Garry, the engineer who had installed the engine was confident it would be alright, the diesel engine he said was working fine. So without any practical knowledge regarding the hybrid side of things we reluctantly agreed, we had no choice, by this time we were homeless.

Eventually by late May 2014 Art Deco was completed and ready to make the journey south for her launch into the Grand Union canal. Our son, David, had created a website for Art Deco, ready for us to market her as a short break destination and I took the opportunity to record the build as it went along. What follows are the posts that I put on the website and they document the events as they happened, warts and all. I should point out that all names have been changed to protect the guilty!!

1st November 2013

Well it’s been a long time coming, but at last here it is, the first blog following the build of the wide beam canal boat "Art Deco". We have had a few set backs along the way, all did not go to plan, perhaps we were a little too optimistic, but now we are over the Pennines in Lancashire, living in a rented apartment in Salford for six months whilst the boat is fitted out. The shell is complete and will be transported by road from Stafford to Manchester where Brian the boat fitter will fit out the interior. This should be completed by early Spring of 2014 and then the finished boat will again be transported by road (it is too wide to pass through the locks around Birmingham) and put in the Grand Union Canal around Watford, from where we will cruise to our mooring at Roydon Marina on the river Stort in the Lea Valley Country Park.

5th December 2013

The boat shell arrived in Manchester yesterday, HOORAY!! And what a stressful day it was, I should have been prepared due to the history of this project, but I wasn’t. All is now ready for the final fit out which should take around twelve weeks so we are on course for a launch just before Easter next year. This deadline is set in stone, as we have to be out of our rented apartment by 16th April and we don’t want to extend this. Joyce has told Brian that we will live on the boat at the yard if necessary!

11th December 2013

The shell is now in the workshop, the inside being fitted out and the outside painted in our chosen colours by Brian and his team. After applying up to four coats, which will take about three weeks, the outside will be ready for me to paint the graphics, something I am really looking forward to doing. I intend to start painting the graphics in the first week of January so I will be on site to watch the progress of the build as it turns from a great hunk of metal into a beautiful boat.

20th December 2013

Into the third week of the build and I am glad to say that now things are really progressing, the fitters and painters are hard at it and Joyce and myself, along with help and advice from Brian are madly buying all the things needed for the fit out. It is great to have a blank piece of paper and start from scratch; we sold most of our furniture along with the apartment to a first time buyer, so we are able to furnish the boat as we want. We have already ordered the furniture for the saloon and this week have ordered all the wet room and day toilet fittings and tiles. We are in the process of planning the kitchen, this has not been possible until now because we need the insulation in and boarded out to get exact measurements and we are tight for space.

The kitchen is Joyce’s domain, so she tells us what she wants and Brian and myself try and fit it in. Her list is; oven, induction hob, microwave, warming drawer, cooker hood, dishwasher, washing machine, fridge, freezer, sink, and various cupboards and drawers, all in a space of 7’6” x 12’! It is amazing what you can do with a bit of careful planning; Brian has been building boats for over twenty years so he can use literally every inch of space. All the insulation and boarding out will be completed before the Christmas break, then the central heating system will go in, it can then be used during the rest of the fit out, we have to keep the fitters warm, they will work better and this should help make the deadline! The hybrid engine is ordered and should be here early in the New Year; that will be a major stage and is an exciting prospect.

On a personal note, our car of twelve years and 160,000 miles finally gave up the ghost a couple of weeks ago. We had been over in Sheffield and were on our way home when it just died; fortunately it was right outside my mate Mak’s house! Thanks Mak for the lift to my sisters and thanks to Ann and Malcolm for putting us up for the night. The car was going at the end of December, so it is not a big deal, as we don’t plan to have one when we are on the boat.

That’s all for now, Merry Christmas and Happy New year, watch this space for the next blog in the new year, hopefully we will have a gallery to post more photos by then.

10th January 2014

The build is progressing nicely; not very exciting at the moment, but it's the things you don’t see, such as insulation, that are important. Get that wrong, then you are in trouble later on. It’s the same with the painting, Alan the guy who is painting the boat is a true perfectionist, he had primed and undercoated the whole boat but was not happy with the finish, and some of the welds were showing, so he got to work with the angle grinder, smoothed them off and started again with the primer and undercoat. He is now putting on the final coats, so I should be able to start the sign writing next week, hooray!! I will then be involved on a daily basis with the build and will be on site as the exciting work begins. Look out in the next few weeks for more interesting photos!

On a different note we went to Roydon Village Marina this week where the boat will to be moored, it’s very nice and the people are very friendly. A bit more rural than we expected though, but it has all the facilities we need. There are all the usual maintenance facilities for the boat, and a clubhouse with cafe, bar, toilets, showers and laundry facilities. And there is also a restaurant on site. Roydon village itself is very up market with three pubs, a lovely old church and village green that is mentioned in the Doomsday Book, but on the downside there is just one small shop that contains the off licence, post office and grocery store. On the up side though Roydon Railway Station is only 10 minutes walk away and there are local trains that link all the nearby towns, and fast trains into London Liverpool Street, which is only thirty minutes away.

We had a quick look around the area, Broxbourne looks like a great little town with lots of interesting shops and Harlow is larger with all the usual chain stores and supermarkets, and both are on the railway line. The whole area is within the Lee Valley Country Park which has plenty of recreation facilities such as walking and cycling routes, RSPB sites and plenty of water sports, so this will be a big plus when we start marketing Art Deco as a holiday destination. That’s all for now, hopefully there will be more to see on the boat build next time.

8th February 2014

Finally, at last I have started painting the graphics on the boat. It’s been a long time coming as Alan the painter is a true perfectionist and was not happy with the finish until he had put EIGHT coats of paint on the sides. I told him it is not a Rolls Royce finish that we are after and that boating on the canals and rivers of England is a contact sport, but he insisted on getting it perfect; it puts me under pressure now to come up to his standards with the painting of the graphics. It has actually gone well, quicker than I expected, it’s been a long time since my hand lettering days on the drawing board before the invention of the Apple Macs and I was not at all confident that I could still do it, but its a bit like riding a bike, it all comes flooding back! The only down side is the actual colours, I had a limited pallet to choose from, there is not a great range of boat paint out there, just one brown and one pink and now they are on the boat they are too vivid, not the subtle colours I wanted so I will have to add white and mix to get the correct colours and repaint. I will have to paint the other side in the original colours first though so that they both look the same and then paint over with the correct colour, not as bad as it sounds as I really enjoy being at the boat yard and being involved in the build.

The up side is that I am on site all the time and can keep an eye on the build and make changes and solve problems as they arise. There is so much involved with the build, not just the usual stuff like where light fittings, switches and plug points go, but things like where to put the water and effluent tanks, and where to hide the pumps for these, and not least of all where to put the TWO TON of batteries needed for our hybrid installation. These will hopefully fit in the engine room at the back of the boat, but there may need to be an adjustment in the ballast as none of us were aware of the scale of the battery requirements; this is the first hybrid installation that Brian has done. We will also have to make sure there is adequate ventilation as the batteries need to be kept cool, I am sure all these little problems will be solved as we go along.

So now its all plumbing and wiring at the moment, all the kitchen appliances are due in next week so we can make a start on the kitchen, the two bathrooms are ready to tile and fit out and then it’s just the bedrooms to complete then the inside will be done. That just leaves the engine, batteries, generator, gearbox, prop shaft, propeller, control gear and power management system to complete - no problem! That’s about all for now, nine weeks to go on Wednesday 12th February, so it’s full speed ahead!

12th March 2014

With Spring defiantly in the air this week we are working to an end date that is now set in stone as we have given notice on our apartment here in Salford: we have to vacate on Tuesday 15 April - 5 weeks time. The fit out is going to schedule and with the first fix now complete, the guys are moving on to fitting out the bedrooms and bathrooms which should be completed in a few days. The living/dining area needs no fittings as we are using domestic furniture - two new leather settees along with the Italian glass “air” units, coffee table and standard lamp from our apartment in Sheffield. We also have an open fire, designed especially for a boat fuelled by Ethanol that will be fitted along with a new 42” Smart TV, and our fold down glass table etched with our rose logo. Then we have the kitchen to fit out which will take around a week, so long as we can squeeze in all the appliances we have! That just leaves the question of the engine that has not arrived yet, but I am assured that it is on its way and should take a week at the most to fit, so we are not panicking yet.

Since the last blog I have repainted all the graphics and I am much happier with the colours now. The photo shows the difference, not much I hear you say, but trust me the colours are much more subtle and give the overall visual effect I wanted. I just have to paint the name on the bows now then all the graphics are complete. That's all for now, hopefully in a couple of weeks I will blog the engine fitting.

9th April 2014

Stressful times, the boat won’t be ready for our deadline and we have to vacate our flat in Salford on Tuesday next week (15th). Fortunately after Joyce’s last email stating that this might happen we were offered a cottage in the Peak District by a couple of our Cafe customers who are absolutely fantastic and we are so grateful, sleeping on a part finished boat did not appeal. We will only need an extra week on the build, so hopefully we won’t be too much of a burden on our kind friends, and there is a rail station near the cottage, so I will be able to get to the boat yard and wave a big stick. Boat builders, I have learned, are notorious for letting deadlines slip. To be fair though the quality of finish and attention to detail is excellent so that is some consolation.

There have also been unforeseen problems, namely with the engine being too long. There is masses of space either side, which is good because we need the space for all the batteries, but it is the hybrid part that fits at the rear of the diesel engine that is the problem. It would just about go in, but servicing would be a problem so we have solved this by cutting away part of the bulkhead between the engine room and the kitchen so that access can be gained from the kitchen. It has actually worked out okay though, as servicing the hybrid, which has three drive belts and many electrical connections will be very easy via a removable panel in the kitchen, which will be hidden behind the rear stairs, and it only encroaches into the kitchen by about three inches.

The rest of the fit out is progressing, the wet room and second toilet are fully tiled, the two bedrooms have their wardrobes and cupboards built and all the kitchen units are in place and the Corian work tops have been delivered, but the kitchen can’t be finished until the engine is commissioned, which is not straight forward as the manufacturers are situated in the Isle of Wight and they have to do the work.

The boat WILL be complete and ready to transport down south by the week of Easter Monday so I have to find a place to drop it in the water, not as easy as I thought due to the size and weight. After many phone calls I have found a marina near Watford who can do the job so that is where we will start our adventure from, nearer to our base than Northampton where I had originally planned, so not as many locks to negotiate which makes Joyce very happy indeed.

30th April 2014

Under normal circumstances our position would be the envy of most people: Idyllic location, comfortable country cottage and great weather. Unfortunately for us things could not be more stressful and frustrating, two weeks after our original deadline and the boat is still not finished. I won’t bore you with all the issues, but we are now at the stage where others apart from Brian and his team are calling the shots. It was difficult enough dealing with one set of craftsmen, but now we have the engine fitter, the battery and electrics engineers and the hybrid manufacturer to deal with, it’s not easy.

On a positive note the diesel engine is fitted and running and the batteries and electrics should be completed today (Wednesday). The hybrid engine has to be commissioned which hopefully will happen before the end of the week, and then Chris can finish off the galley, which should complete the fit out. All we need then is a certificate of worthiness and we are finished! It’s then the logistics of transporting the boat to Watford and getting it put in the water, which hopefully will happen in the week of Bank Holiday Monday. We cannot thank our hosts here enough; they have been fantastic and very helpful and understanding in our time of need. I have included a couple of photos, not much new to see but the French windows are in and lots of detailed finishing off has been done and another major job is the bow thrusters have been fitted. Next week I will post pictures of the lift, transport to Watford and final drop into the Grand Union Canal. I will, I really, really hope I will!!!

Joyce had not been idle while I had been at the yard painting the graphics, she had secured a mooring for Art Deco in Roydon marina on the river Stort, near Harlow in Essex. We had decided to have a marina mooring for the first three months, given the problems we had experienced. We thought this would allow us time to iron out any potential problems before we became continuous cruisers. Exhaustive research had revealed that the nearest place to the Roydon marina with a crane able to lift the 28 tons that Art Deco weighed was at Watford, just by Cassiobury park on the Grand Union Canal. We arranged transport and on the morning of the 21st May a crane arrived at the yard and lifted the completed Art Deco on to a low loader for the journey south. I had managed to persuade the driver to let me travel in the cab with him, and at 10 am I left the yard with a great sense of relief. It had not been an easy build, we had had many heated arguments along the way, especially around the time the build was taking, but eventually we got there and we were now on the final leg.

Well it finally happened, the boat has left the unit but as usual for this project not without Incidents so bear with me this may take a while! The transport and crane were booked in for a 8am start on Wednesday 21st at the boat builders and as we were at that time staying in Sheffield with my sister and brother-in-law (yes we had to beg another bed for a couple of weeks!) I booked into a bed and breakfast in Manchester on the Tuesday evening and although I had pre-booked on the Monday they had no reservation for me. I had taken the phone number from the Internet and had spoken to a guy who booked me in but no males worked at the place, only women ran it, but fortunately they took pity on me and found me a bed for the night.

So at the boat builders for 8am, crane and transport already on site, it’s a hive of activity and we start to slowly pull the boat out of the unit. All is going well until the supporting bogie wheel collapsed and the boat was grounded. Fortunately by this time the boat was 95% out of the workshop so the amazing crane driver was able to manoeuvre the boat out, over the wall and on to the low loader - brilliant although the whole operation took over five hours, not the one hour predicted. So not away until after 1pm, knowing the boat yard we were heading for closed at 5pm sharp, a tight deadline.

We were making good progress and were on schedule to just about make it until the truck had a blow out on the motorway, nothing we could do but wait for rescue, which took two hours so, no boat in the water today. The boat yard could do the lift at 8.30am sharp the next morning so we found a place to park up close by and myself, Ian the driver and Wayne the support vehicle driver went to the pub and drowned our sorrows Did not have too much to drink because I was sleeping on the boat and had a fifteen-foot climb to get on!

Up the next morning and the boat was in the water for 9.15, hooray finally what a relief, but it was not to last. At 3pm I was told that I would have to move now as they had another boat to lift out of the water, panic, I was alone and had not even started the engine on this boat but had no choice but to go for it. Actually I did all right, even filling up with diesel and water on the way to a mooring place on the canal. It was not until I climbed off the boat with the ropes ready to tie up that I realised there were no mooring rings to tie up to, all the other boats had mooring stakes driven into the bank and I had none. Fortunately a fellow boater came along and helped me and that is where we are now.

Joyce came down from Sheffield by train arriving at 3pm on Friday and we have spent the weekend and bank holiday unpacking boxes, resulting in a mountain of cardboard which we have somehow to get rid of, not sure how as we have no transport. Hoping to start the journey to Roydon tomorrow if we have solved the problem of the ballast needed to trim the boat so we can use the bow thrusters.

The time on my own allowed me to familiarise myself with our new home, and get my head around the one area that had been giving me sleepless nights; the electrics. I had been at the yard when the engine was fitted, complete with the hybrid adaption, and watched as the massive bank of batteries were installed and connected up. What concerned me most was the shear thickness of the cabling used, it was a good centimetre in diameter. There was a phrase rolling round in my head, that was used in the manufacture’s literature which stated; ‘There’s enough power in the battery bank to fry an elephant!’ I needed to understand the system and quick. I had watched the engineer as he fitted and connected it all together and he explained each process as he went along and the theory seemed quite simple, but what it would be like in practice was another matter.

We had two separate electric systems; a 12 volt DC system that powered the cabin lights and water pumps and a 240 volt AC mains system, very similar to a domestic set up, that powered the galley and 13 amp plug sockets. The 240 volt system took power from the 48volt battery bank charged by the 48 volt alternator via the inverter, and the 12 volt system from two leisure batteries connected to a 12 volt mains charger. These two systems were independent from the engine electrics which were unchanged from the standard Beta 75 engine. There was a gauge on the back deck which registered the amount of charge in the batteries at any one time and the number of amps generated when the engine was running. It also registered how much power was being taken out of the batteries when the engine wasn’t running.

On my short run from the marina to the mooring I had been too occupied just steering the boat and had no time to look at the gauge, that would be something to address on the long cruise to Roydon. I have to admit that I was concerned about the journey, it was a long way for our first cruise and I didn’t know enough about the electrics, there is a lot of power in the system, and as every school boy knows, electrics and water are never a good combination.

Joyce arrived in Watford at the end of May and stepped aboard Art Deco for the first time on water and was amazed just how stable she was compared to the craft we had experienced on the Norfolk Broads, they seemed to move with every step. We spent a few more days moored at Cassiobury, familiarising ourselves with our new home, stocking the fridge and freezer with food, filling the water and diesel tanks to capacity ready for the journey north via the Grand Union canal, and the rivers Lee and Stort to Roydon marina.

One last job I wanted to do before we set off on our maiden voyage was to get the boat sitting better in the water. There was a large hold in the bow that would normally take the gas bottles, but as we were all electric it was empty, ideal to fill with ballast I thought. I arranged for the local builders merchant to deliver five cwt. of concrete blocks to the service quay of the marina and moored the boat there to load up. As I stepped off the boat I slipped and fell into the canal. With water up to my waist Joyce could not help me as she was in hysterics laughing at my predicament. Fortunately I saw the funny side of my baptism, I now felt like a true boater. After I had dried off, the two of us loaded the concrete blocks in the hold, but unfortunately they only lowered the bow a few inches. It would have to do, we were keen to be on our way. Another task that would have to wait until Roydon marina.

It had been 3 years in the making, but finally on the morning of Wednesday 27th May 2014 we left the mooring at Cassiobury and cruised off into the unknown. It was a new chapter in our lives and we were excited and a little nervous, what lay in front of us we had no idea but we had taken chances before and we were still around to tell the tale.

Whatever happened it had to be better than sitting watching daytime TV!!

Traditionally made from toasted or fried pieces of pita bread, mixed greens and salad veg with a tangy lemony dressing. This salad is perfect for using up an odd leftover wrap, pita or flatbread. Bring a pan of water to the boil and add your choice of green beans or peas. Boil just for a minute or so, until tender then drain and sit in cold water, this keeps the colour and stops the cooking process to keep a nice crunch, drain again. Halve a piece of cucumber lengthways, scoop out the seeds and cut into half-moon shapes. Whisk together 2 tbsp olive oil, juice of half a lemon, ½ tsp sugar and a pinch salt and black pepper. Open up the wholemeal pitta bread into two pieces and cut into bite size pieces, dry fry in a pan to toast, oil can be used but not necessary. Finely chop any fresh herbs such as parsley, coriander, mint or chives. Don’t worry it you don’t have any, you can substitute with mint sauce out of a jar. Combine everything together with some crumbled feta cheese, season with a pinch of sal flakes and freshly ground black pepper to serve.

Traditionally made from toasted or fried pieces of pita bread, mixed greens and salad veg with a tangy lemony dressing. This salad is perfect for using up an odd leftover wrap, pita or flatbread. Bring a pan of water to the boil and add your choice of green beans or peas. Boil just for a minute or so, until tender then drain and sit in cold water, this keeps the colour and stops the cooking process to keep a nice crunch, drain again. Halve a piece of cucumber lengthways, scoop out the seeds and cut into half-moon shapes. Whisk together 2 tbsp olive oil, juice of half a lemon, ½ tsp sugar and a pinch salt and black pepper. Open up the wholemeal pitta bread into two pieces and cut into bite size pieces, dry fry in a pan to toast, oil can be used but not necessary. Finely chop any fresh herbs such as parsley, coriander, mint or chives. Don’t worry it you don’t have any, you can substitute with mint sauce out of a jar. Combine everything together with some crumbled feta cheese, season with a pinch of sal flakes and freshly ground black pepper to serve.