starry, starry nights

I should start off with a confession – I have never sailed on a canal. Ever. I have walked along canals, and gazed wistfully at the beautiful boats drifting past, but I have never negotiated locks, or sat on the deck of a boat sipping a glass of wine at sunset. I’ve never even set foot on one. So why is this landlubber writing for CANALS ONLINE?

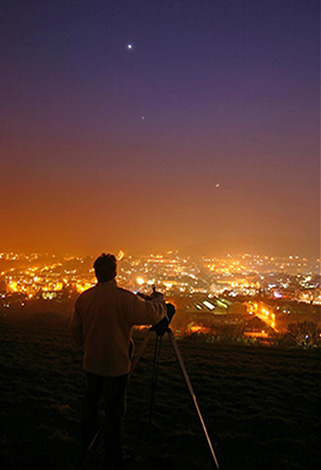

Because I am on a mission to spread the word that sky watching is a hobby that can be done anywhere, by anyone. Several times a year my partner Stella (her actual name, yes) and I, and our cat Jess, leave the real world behind and head off to Kielder Forest in Northumberland to spend a week or so in our caravan under some of the darkest skies in the UK. Up there, at the beautiful Kielder Campsite, away from the light pollution that blights our towns and cities, the stars shine like jewels tossed up into the heavens, the Milky Way looks like it is airbrushed across the sky, and when it is visible the Evening Star, Venus, actually casts shadows.

I’ve written articles and features about “camping astronomy” for many magazines, and many people have told me that they inspired them to look at the night sky for the first time during their holidays, taking advantage of being under skies much darker than those they have at home. The last time we were up at Kielder a couple told me that the only other time they had seen such a beautiful sky was when they were on a canal holiday – and it got me thinking. I’d never thought of that before! But it made sense that people holidaying on our canals would sometimes find themselves in remote places, under very dark skies, wishing they knew more about what they were seeing “up there”.

If you’re one of them, this is for you.

Let me take your hand, lead you outside, away from the TV, and introduce you to the night sky...

Obviously I have no idea if you are reading this on holiday or at home, but it’s a safe bet that at some point in your travels you will find yourself somewhere far away from the streetlights and security lights that dim our view of the stars these days. This “light pollution”, the arch-enemy of stargazers amateur and professional, means we can only see the brightest stars from our towns and cities, but from a remote country location you’ll see thousands . I know from my own experience that most campers and caravanners have looked up in awe at a star-dusted sky – perhaps walking back from the toilet block in the middle of the night or trying to slide their campervan door open quietly after an evening at the bar – and wished they knew more about it, and I imagine CANALS ONLINE readers are the same. So where do you start?

Simple. Just put on a warm jacket, go out and look up! If you’re moored somewhere dark you can get started right away, but you might need to get off and look for a darker place nearby. If you do, be sure to stay safe, and go with company.

And then? Then you wait.

As long as the Moon isn’t in the sky, as soon as you look up you will see a few stars, maybe a dozen or so, but if you take the time to become “dark adapted” you’ll see many, many more, as your eyes release special chemicals which make them more sensitive to faint light and open up their pupils wider than usual too.

After half an hour or so – and during that time don’t be tempted to sneak a look at your phone, its bright screen will send you right back to square one! - you’ll see that the sky is full of stars, and there are two main differences between them. You’ll see that some are brighter than others, and that they’re not all the same colour. To understand the reason for these differences you need to know what stars actually are. Concentrate; here comes the science part...

Many centuries ago, long before Professor Brian Cox stood on a mountain top with his hair wafting in the wind, waxing lyrical about the beauty of the universe, people had some very funny ideas about stars. They thought they were holes in the fabric of sky, allowing a heavenly light to shine through from another universe or realm, or that they were mystical objects surrounding Earth, flickering and flashing with reflected sunlight. After centuries of study with telescopes, satellites and space probes we now know stars are actually enormous balls of hot gases, incredibly far away, like our own Sun. In fact, if you’ve ever looked up at the Sun on a hot summer’s day you’ve already done some astronomy!

Why? Because the Sun – you know, that blindingly-bright object you sometimes glimpse in the sky while on holiday - is simply the closest star to the Earth, and all the stars we see in the sky are distant suns too.

And those different colours? They are an indication of how hot they are. You might instinctively think that a red star is hotter than a blue one because we’re used to thinking of red things being hot (fire) and blue things being cold (ice), but in fact the exact opposite is true for stars: red stars are cooler than white or blue stars! Red stars have surface temperatures of around 3,000 deg C, while blue stars are around 10,000 deg C! It actually makes sense if you think about the different temperatures of flames: a flickering yellow candle flame is a lot cooler than a bright blue-white flame shooting out of a blowtorch.

The brightest few hundred stars have their own names, many of which you’ll be aware of even if you’ve never looked at the night sky. The names of stars like Vega, Deneb, Altair and Antares are familiar to us through science fiction films and TV series, through advertising and song lyrics.

They’re everywhere.

But not all stars are the same. Some stars are faint, some bright, but just because a star is bright in the sky that doesn’t mean it is close to us. It might actually be a low energy star that only appears bright because it is very close. Likewise, a faint star might actually be a very powerful star that only appears dim because it is a long, long way away from us. If you imagine stars as celestial light bulbs, of different sizes and wattages, shining different distances away from us, you’ll get the idea.

Once you’re properly dark-adapted the next thing you’ll notice is that the stars make patterns and shapes. It’s as if the sky is a huge join-the-dots puzzle stretched out above your head. You might already know a few constellations – most people can recognise the pan-shape of the “Big Dipper” (also known as “The Plough”) and probably the pinched hourglass shape of Orion too - but that’s about it. There are actually 88 patterns in the sky, and they are known as constellations.

You already knew that, I’m sure, but you need to prepare yourself for a surprise here - the Big Dipper isn’t actually a constellation.. !

The star pattern we call “The Big Dipper” is an ‘asterism’ , a small pattern of stars that is very striking to the naked eye, which forms only part of an actual, much larger constellation. The Big Dipper represents the tail and body of Ursa Major, The Great Bear. If you’re moored somewhere with a dark sky you’ll see the fainter stars around it which make the bear’s legs and head, but you’ll struggle to see them from anywhere with light pollution.

The Big Dipper is very useful for finding the most famous and important star in the whole sky – Polaris, aka the Pole Star . Time for Surprise number 2: despite what many people believe (and give as answers on TV game shows or in pub quizzes) the Pole Star is not the brightest star in the sky!

In fact the Pole Star is only the 50th brightest star in the sky, only as bright as the Big Dipper’s stars.

Polaris is only important because it is the only star in the sky that doesn’t move – positioned directly above the Earth’s north polar axis, as the Earth spins all the other stars wheel around it.

Finding the Pole Star is easy. Two of the Big Dipper’s stars, called “The Pointers”, point right to it.

From the UK Polaris and the Big Dipper are visible all year round, but that’s not true of other stars and constellations. We don’t see the same constellations all the time. Every season has its own sky because as the Earth orbits the Sun we look out into different parts of the universe at different times of the year. So, many of the stars and constellations we see in the summer are not visible in the winter, and vice versa.

This means that it’s impossible to “learn the sky” in one night, or even in one week or one month. It takes a whole year to learn all the stars and constellations visible from where you live.

What else can you see up there on your next clear holiday night, apart from stars and constellations?

Well, if you can see a star that is very bright, so bright it really catches your eye, this is almost certainly a planet. We can see the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn in the night sky with just our naked eye, and a sixth, Uranus, with a pair of binoculars, if you know where to look. The seventh, Neptune, needs a small telescope to see it. Of those planets, Venus and Jupiter can appear strikingly bright in the sky, so bright they are sometimes reported as UFOs! How do you tell stars and planets apart? Simple. Stars twinkle, planets don’t.

Which planets will you be able to see when you go out stargazing? That depends on when that is. Because planets change their position in the sky from night to night, week to week and month to month it can be hard figuring out which one is which. Charts in books and magazines can help you identify them but the easiest thing to do is download a "planetarium app” on to your phone before leaving home. (see the info box)

What else can you see in the sky when you look up on a clear, dark night?

Well, if the Moon is up you’ll suddenly realise just how bright it is, how its blazing silvery-blue light drowns out almost everything else. Out in the dark countryside the brightness of the Moon often shocks town- and city-dwellers. But the Moon doesn’t look the same all the time. You’ve probably already noticed that, as the month progresses, the Moon appears to change shape from a fingernail-clipping thin crescent hanging low in the west after sunset to a dazzlingly bright disc in the southern sky late at night and finally to a crescent again in the eastern sky before sunrise. These different shapes are known as the “Phases” of the Moon, and they’re caused by sunlight illuminating different areas of the Moon as it moves around the Earth.

By the way, despite what those fun-loving minstrels Pink Floyd told us, there is no “Dark side” of the Moon. As it whirls around the Earth all of the Moon is illuminated by the Sun at some point, but because the same side faces us all the time, it just appears to us that the other side is always dark. It’s only “dark” in the sense that we used to know nothing about it, until satellites and Apollo capsules orbited the Moon and sent back photos of it.

If you’re lucky you might see a shooting star zip across the sky while you’re looking up. Astronomers call them meteors, but another popular name is “falling stars”, which is ironic really because they aren't stars at all. Meteors are tiny pieces of space dust burning up in Earth’s atmosphere. Meteors have a reputation for being very rare – so rare it’s traditional to make a wish if you see one – but on most nights you will see a few shooting stars falling at random, and on certain nights of the year we can see many more – a meteor shower. These happen when Earth ploughs through a stream of space dust left behind by a passing comet, and then, for a few nights in a row, we can see dozens or more shooting stars every hour – weather permitting, of course. There are around half a dozen good meteor showers every year, and lots of more minor ones too. If you find yourself under a dark sky in mid-August you’ll be able to watch the annual Perseid shower, which is one of the best of the year. It reaches its peak after midnight between Aug 10th and 14th and if you look up then you’ll definitely see more shooting stars than usual. Eventually. If there’s no Moon in the sky. And if you don’t fall asleep...!

One of the most beautiful sights in the night sky is the Milky Way , but you will only see that if you’re under a really dark sky between late August and early October, because that’s when it’s best seen from the UK. To the naked eye the Milky Way looks like a misty band of light cutting the sky in half, almost like a long, faint cloud of smoke rising up from a distant campfire, but if you look at it through a pair of binoculars you’ll see it’s actually made of millions of faint, pinprick stars...

When you stare up at the Milky Way you’re looking at our true home in the universe. Here comes another science section...

As you now know, our Sun is a star, but it is just one star in a truly enormous group of over 200 billion stars – a group we call the Milky Way. We now know, after centuries of study, that the Milky Way as a spiral shape, like a huge Catherine wheel. We also know it is spinning as it moves through through space, but unlike a Catherine wheel that whizzes around so quickly it is just a blur, the Milky Way spins so slowly it takes 250 MILLION years to rotate once.

Astronomers love looking at the Milky Way, but find it very frustrating too. It rankles, knowing that if we lived on a planet above or beneath the plane of our galaxy its beautiful, curved spiral arms would fill half the sky but instead, cruelly, because our Sun is located inside the Milky Way’s flat disc all we see is a band of light. But that’s just us being grumpy. For everyone else, the Milky Way is still a stunning sight on late summer nights.

There can’t be much more to see, surely? Oh yes, there is! When you’re out stargazing – or even just walking back to your boat at the end of the day - sooner or later you’ll see what looks like a star moving across the sky, or more likely several of them. These are satellites , and they criss-cross the sky all through the night. The brightest satellite we can see is the International Space Station, which can look like a bright silvery spark sailing silently across the sky from west to east, but there are now many thousands of fainter satellites up there too. If you see a trail or “train” of stars chugging silently across the sky, like beads on a string, they will be some of Elon Musk’s Starlink satellites, and although they might look pretty, astronomers are very concerned about how they are changing the appearance of the sky and ruining astronomers’ efforts to study the universe. By 2030 Starlinks and satellites like them will outnumber the stars...

There’s a lot more to see up there but that’s more than enough to get you started. Hopefully you’re now prepared to go out and start stargazing on the next clear night. It’s not rocket science. You don’t need a fancy telescope or even an expensive pair of binoculars. All you have to do is wrap up, go out, and look up. Once you’ve dipped your toe in the cool, still waters of the cosmos and seen what’s up there, holidays – or life - onboard your boat will never be the same.